Germany has gradually become, during the past decades, one of the most influential countries on the geopolitical map. It is thus no wonder that the upcoming German elections have drawn a lot of attention.

Even if it punches above its weight, the tiny Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and its upcoming elections (for the local councils this October 2017 and for the Parliament next year) do not elicit quite as much interest from the international political commentators.

While understandable, that is a pity, all the more so after the latest “State of the European Union” speech of President Jean-Claude Juncker (probably the best known Luxembourger) setting the direction toward a future EU which should be both more integrated and more flexible.

Located centrally, very open and very European, Luxembourg is a unique crucible in the laboratory of the future EU.

The Luxembourg political landscape displays many resemblances to the German one but for the fact that in the role of the incumbent, Luxembourg has the “Demokratesch Partei” (DP, an ideological cousin of the German FDP) of Prime Minister Xavier Bettel while the “Chrëschtlech-Sozial Vollekspartei” (CSV, an ideological kin of Germany’s CDU/CSU), after having led the country for more than 18 years (under Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker), has been in opposition since 2013 at national level and since 2011 in the City Council of the capital (Luxembourg City).

A country “calm and comfortable”

When following the current Luxembourg local elections campaign, one can only be struck by the parallels with Germany. The underlying cause: just like Germany, Luxembourg is “a country calm and comfortable”, as Charlemagne puts it in a “The Economist” article titled “Germany’s election campaign ignores the country’s deeper challenges”.

That is to the credit of the Luxembourg political class. The four major parties (the Socialists of the LSAP and the Greens of “Dei Gréng” complete the roster) share a similar worldview. Just like its bigger neighbour, the country is prosperous, a land of advanced manufacturing (Goodyear has its European R&D centre here and has recently announced an investment in a new high-end tire-manufacturing facility), a remarkable international financial hub and is also the seat of highly visible European institutions such as the European Court of Justice. The question The Economist asks with respect to Germany applies perfectly well: “If it ain’t broke, why fix it?”

“[T]hat would be a mistake”, answers Charlemagne, referring to Germany. In the long term, Luxembourg too “faces enormous challenges which might force its leaders to make difficult and divisive choices”. Could Charlemagne’s answer apply to Luxembourg as well?

Unlike Germany, Luxembourg doesn’t need to worry unduly about geopolitical turbulence. A small and rich country safely nested at the heart of the EU, it will always be able to offer more than expected or asked for by its bigger neighbours.

As far as the economy is concerned, while the deep transformations that loom large for all the countries will be trying, Luxembourg has always managed to give the commands to sharp-witted politicians, fast to make the right decisions and seize the opportunities. Its size is an advantage, allowing it to easily sail the changing winds. Take Brexit for instance: Luxembourg’s financial centre is well positioned to benefit from a shift in business flows away from London. But unlike bigger financial centres such as Paris, Frankfurt or Amsterdam, it doesn’t need to expend too much effort because in a country so small, a marginally positive increase in jobs (a number that would not register in bigger capitals) is enough to give a healthy boost to the economy.

However, if a small size is an advantage for keeping the wealth-creation humming, it becomes a risk when confronted with rapid changes in the structure of the social body. The vigorous performance of its economy and more specifically the contrast between the dynamism of Luxembourg and the relative torpor of the nearby regions of Lorraine in France and Wallonia in Belgium have generated a strong influx of mostly francophone workers commuting over the southern and western borders of the Grand-Duchy. The huge prosperity differential between Luxembourg and much poorer eastern European countries such as Romania and Bulgaria has led to an impressive influx of workers from these countries too. These factors generated a high demographic pressure that led for instance the capital to become a city where the Luxembourg citizens are in minority! At the current rate, one can easily picture a future country where the citizens will constitute a minority and the inevitable tensions such a situation will spark.

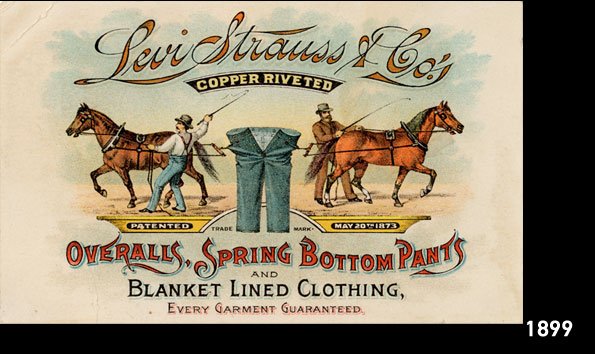

If the “fabric of German society is in flux” as Charlemagne says, that of Luxembourg society is being forcefully torn apart by horses like a pair of Levi’s denims!

Of rising tides and everybody's boats

The politicians of the main parties appear to acknowledge that but, aside from toting dry projections of future population figures (700 000 or 1 million inhabitants), they have yet to spell out a clear vision of what exactly will mean to be a Luxembourger in the next decades and what Luxembourg itself will look like in the next 20 or 50 years. With a Babel-tower like diversity of languages, how are those 700 000 or 1 000 000 people going to communicate with one another ? What social norms and conventions are they going to abide by, how will they reach out to strangers living next to them and initialize new interactions with other people, absent information about how these expect to be addressed?

Take languages first. Statistics are unanimous in pointing out the outstanding multi-linguism of the resident population. The education system is rightly focused on teaching children languages from the youngest age when the brain displays the highest plasticity. By the age of 18, young people typically speak at least four languages (German, French, English and Luxembourgish) and more if they were born in an immigrant family where none of the above was their mother tongue. The common language, learned first, is Luxembourgish. This is natural, yet fraught. Outside the country, not many people are even aware that a Luxembourgish language exists. A modern version of the local German dialect, “Moselfränkisch”, Luxembourgish wasn’t unanimously considered as a full-fledged language until about two decades ago. It wasn’t rare to find even Luxembourgish intellectuals sneering in private at the idea. Out of courtesy, they would switch to French, German or English whenever a foreigner was nearby, which made learning and practicing Luxembourgish difficult for those who came back then to live in the Grand Duchy. Yet Luxembourgish has grown since to fill a role for which it was best placed: that of a glue language allowing 3 and 4 year old children from Kosovo, India or Poland to talk to their little classmates recently arrived from China, Iran and Latvia.

In the world of the adults though, it has become a sort of social sieve, separating the native population from those who, having come to stay, only learned it in adulthood; and the latter from the limited-term expats and those only commuting to work from beyond the borders. More and more, Luxembourgers show impatience with those living in the country yet unable to speak at least a few words of Luxembourgish. They do not bother to switch to another language anymore, an implicit message which surprises foreign residents who had been living there for 15 years or more yet were always spared the need to learn the local language. Non-speakers are thus excluded from the conversation (pending them catching up with the language) which does nothing for interacting, communicating, spreading ideas and has a chilling effect on the creation of social bonds.

Moving further to social norms and cohesion, someone looking at the Luxembourg society may feel unease. Yes, the vast majority of the population is composed of Luxembourgers, Portuguese, French and Italian, all sharing a common “Western christian” culture. Yet the enlargement of the EU has recently seen a strong influx of Eastern European people with a slightly different take on the world. More importantly, the economic expansion led to a significant number of Indians (Arcelor-Mittal is headquartered in Luxembourg and the big Indian IT firms are also present) and Chinese (China has chosen Luxembourg as one of the places where its banks could establish an European subsidiary) arriving for sometimes long spells. The only common denominator of such a diverse society is a certain work ethic in the pursuit of material prosperity. This shared preoccupation is perfect at fostering predictable, cooperative behaviour when times are good but can quickly switch to a dividing factor if ever an economic tempest cannot be avoided. For a more resilient social body, it would be best to imagine additional avenues for people from diverse horizons, different countries or even continents to interact, get to know each other, learn about each other and share laughs and emotional moments.

Beautiful rainbows are mementos that storms still exist

This may seem as an issue every other place would love to have and indeed the success of this little country in managing such a long spell of harmonious growth cannot be praised enough. Yet it is precisely because what the past Luxembourg governments have fostered is so remarkable and valuable that today’s governments, local and central, inherit a great responsibility, for which the political solutions could only grow more intricate over time.

The prize for succeeding is, yet again, pleasantly surprising everybody by bringing to the table of Europe much more than all the other companion States could expect from such a little fellow: a recipe and a path toward a future European demos.