More on Little Edie

As reported in the New York Times Archives titled,

Edie Beak: From Grey Gardens to Reno Sweeney

on Jan. 10, 1978

“Picture me upon your knee, Just tea for two, and two Tor tea …”

The voice was loud though a bit croaky (“I've had a 103‐degree temperature for four days!” the singer complained), and it kept straying from the melody. Naw and then, the singer would ad‐lib new lyrics in place of the familiar old ones, and sometimes the singer would forget the lyrics altogether.

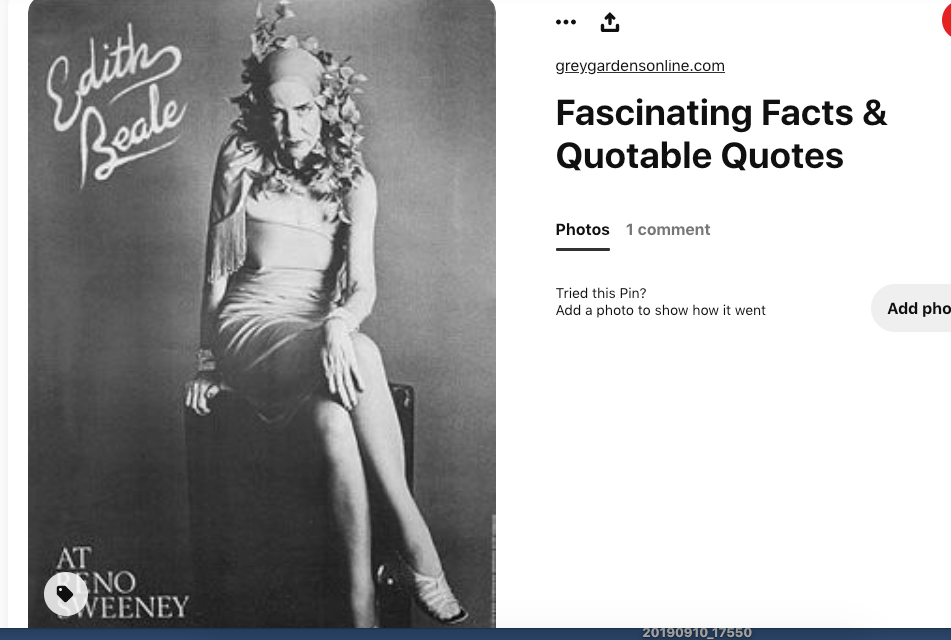

The singer was Edith Bouvier Beale, best known in the past as Edie, Jacqueline Onassis's outspoken, reclusive cousin from Grey Gardens, the decrepit mansion that has long been considered an eyesore to neighbors in chic East Hampton, But now, as she stood by a baby grand piano in a friend's elegant Greenwich Village town house, next to flickering candelabrum, she was rehearsing for what she hopes will be her new life as Edith Beale, cabaret singer. She opens tonight for a six‐day run at Reno Sweeney, the nightclub at 126 West 13th Street.

“I'm finally beginning to live!” said the “over 60':year‐old woman, who spent most of her life taking care of her mother, known as Big Edie, who died last February at the age of 81. “This is a priceless opportunity for me. At the end of my 12 performances, I will know a little more about myself, and what I should do in life.”

Appeared in a Movie

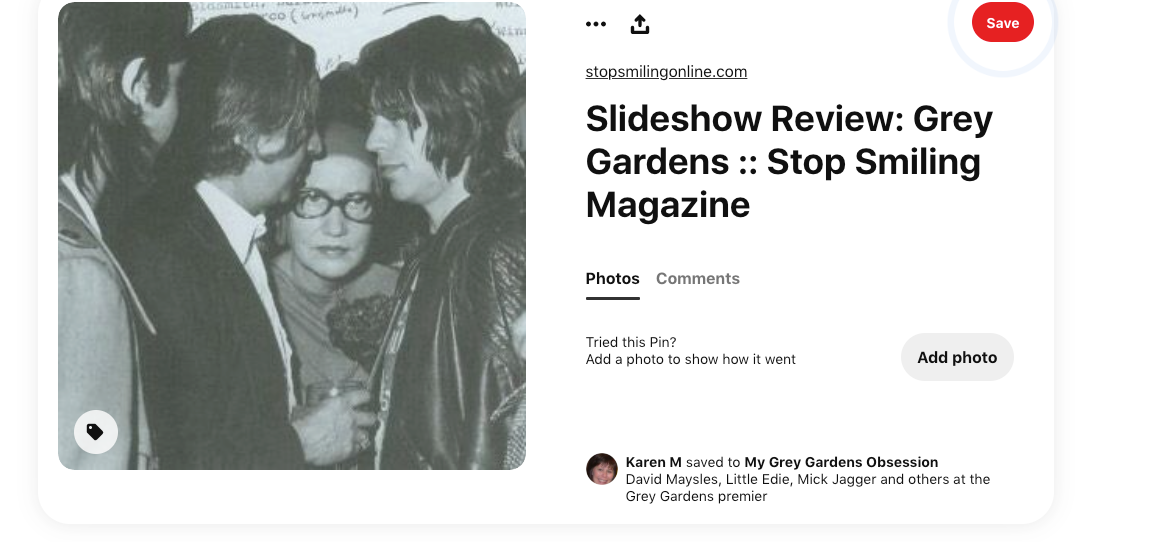

She had a brief fling as a movie star in 1975, when she and her equally outrageous mother were the subjects of a 94‐minute Mayslei brothers documentary film, “Grey Gardens,” which was shown at the New York Film Festival. In it, the two women were shown constantly bickering and romping with their 20 cats in the litter‐strewn mansion, which was raided by Suffolk County health officials in 1971 after annoyed townsfolk complained about its unsanitary, conditions.

“We just didn't have any money to fix it up,” Miss Beale explained. “After the newspaper stories appeared, Jacqueline started sending Mother a small allowance and paying our utility bills. She still does, even though Mother has died. Jacqueline is really a very kind girl, and it almost kills me to take her money.”

Refer someone to The Times.

They’ll enjoy our special rate of $1 a week.

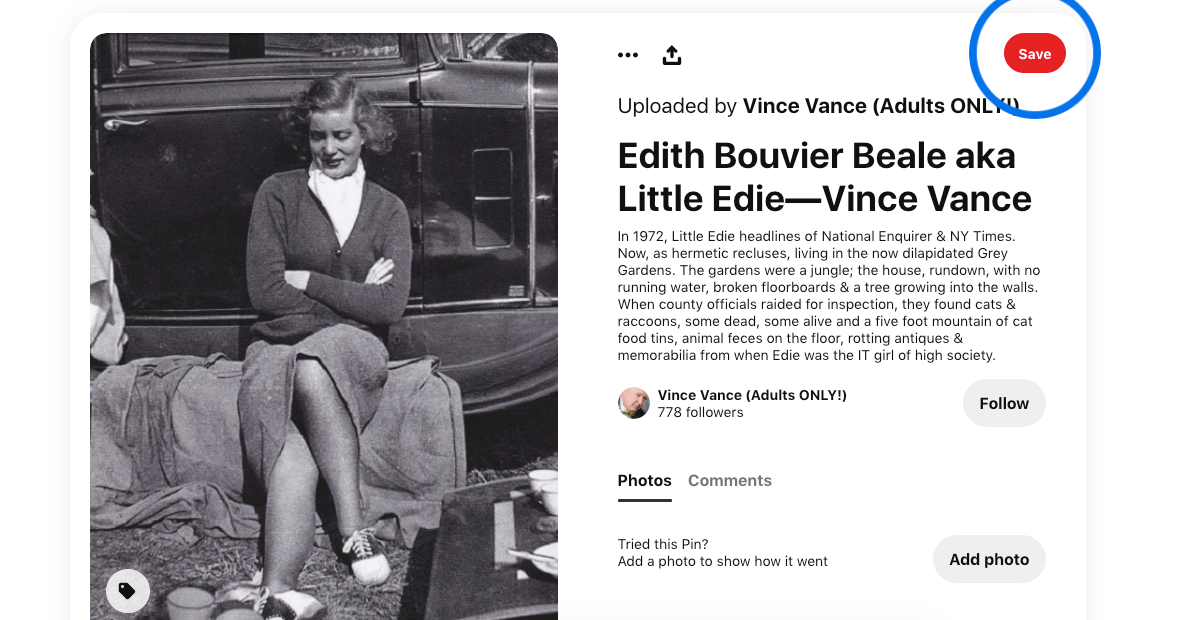

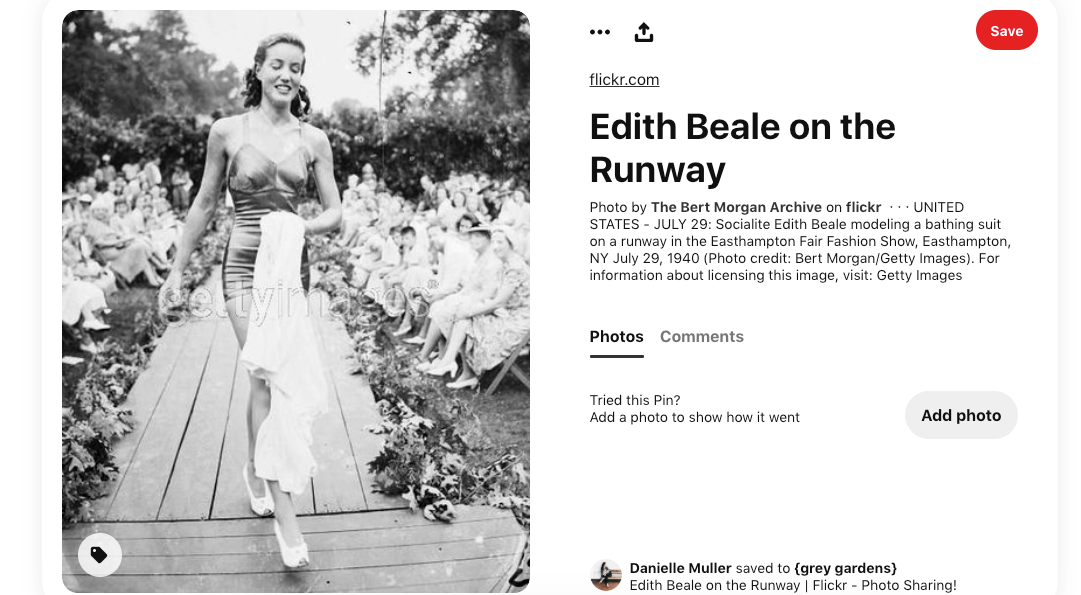

Miss Beale, who kept nervously donning and then removing a pair of thick eyeglasses that she wears as a result of recent cataract surgery, was dressed rather dramatically in a black wool turban, a gray‐striped sweater and gray tweed pants tucked into high black leather boots. Her handsome face looked much younger than its “over 60” years, and her 5‐foot‐91/2‐inch figure appeared almost as trim as it must have been 30 years ago when she was a fashion model in New York.

But it is her speaking voice that one notices most: booming, precise, well articulated, husky, upper‐class, a voice that has definitely known money. (Her late father, Phelan Beale, was wealthy Wall Street lawyer; her late mother, Edith Bouvier Beale, was the sister of Jacqueline Onassis's father.)

“I'm really a dancer, you know,” she said dreamily, during a break in rehearsal. “I really wish I could dance in my act, but I can't see too well yet because of my surgery. When was young, I stopped many a dance in New York City. I really stopped the whole room! I just ad6red to dance. I think I stopped a dance at Princeton once, too.”

Miss Beale said that she had never had any professional training in either singing or dancing. “But when I was a student at the Spence School,” she said, “I was the Shakespearean heroine. They said I had a brilliant future when I left. And then when I went on to Miss Porter's School in Farmington, I got into the glee club.”

Ever since, she has wanted to do nightclub.,work, she said, so when she was approached by James T. Maxcy, owner. of Reno Sweeney, she quickly agreed to work up• an act. It consists of seven songs, including the standards “Tea for Two” and “As Time Goes By,” followed by a question‐and‐answer session with the audience. Her accompanist on the piancy is Lewis Friedman, a founder of Retuf‐Sweeney, who ikens Miss Beale's phrasing to that of Mabel Mercer.

Sneak Preview

Miss Beale tried out her aot at a sneak preview at Reno Sweeney on New Year's Day, wearing an eye patch, a slinky old red dress of her mother's and a feathery red headdress. The audience received her singing politely, with a few titters, but went wild during the snappy question‐and‐answer session. Asked what she thought of television, Miss Beale replied: “It's great for national emergencies.” Her favorite department’ store, she said; was May's, “although ‐I haven't been there. yet.” She dines once a day, at 5 P.M., mainly on fruits and vegetables, she said. And when asked whether she expected her famous cousin, Jackie, to come and see her perform, she replied: “I told her not to come here. I thought she'd upset my act.”

Miss Beale, who is guaranteed minimum of $1,500 for the six‐day stand, scoffed when asked after the rehearsal if she thought she was being exploited.

“Nonsense,” she said. “At my age, I'm lucky to get any kind of work. Besides, this is my dream, what I've always wanted to do. I once had two chances to go to Hollywood, with MGM and Paramount. But my mother didn't want me to go. I was madly in lcive with my mother. She was a psychia and a terrific legal brain, and she always told me what to do. She made all the decisions. She had me absolutely buffaloed.”

And then there is the matter of Miss Beale's financial condition, which she candidly described as “precarious.” “I pay my own taxes, though,” she said proudly. “You have to, or whoever pays them, will gain possession of your house. The taxes are almost $3,000 year, and I'm probably going to have to sell the furniture to pay them. sold the silver to pay the probate fees.”

Miss Beale said she and her mother had received only $5,000 each for appearing in “Grey Gardens,” which was much less than they expected, and which did not last very long. The money “was terrible,” she said “We were very serious, and we actually thought we were going to make profits. Famous last words.” She giggled caustically.

Miss Beale, who stood through much of the interview because, she said, she has a feeling that sitting down “puts on weight,” said she had been living at. Grey Gardens full time since 1952, when, at the age of 34, her mother made her leave her brief modeling career in New York and come home.

“I never lived,” she said sadly. “I never had any options, any choices. I had to go to East Hampton and take care of my mother, or she said she'd die. I have two brothers, but I was the one who was supposed to do it. Decause I was the oldest.”

Despite the constant bickering between the two women in the film. “Grey Gardens,” Miss Beale said she and her mother actually got along rather well, except when it came to the subject of suitable suitors.

“That's the only thing we didn't agree on—the opposite sex,” she said with a smile. “I liked very solid older businessmen, and she liked young artists, musicians and painters. She would pick someone out and say should marry this boy, and I thought she was crazy, out of her mind.”

She sighed. “I think I'll be an old maid until I die,” she said, finally ting down in a chair. “I'll probably sit around with cats the rest of my life. Whatever happens, I certainly won't start to drink. But I do have what you call entrenched habits, and I'm not going to change them.”

Last spring, after her mother's dead% Miss Beale briefly put Grey Gardens up for sale at a price of $500,000. When no one bid, higher than $200,000, she took the house off the market, Now: she's thinking of selling it again.

“I'm probably absolutely insane to sell it,” she said, with a dramatic wave of her right arm. “It's fabulous proper: ty, on a •private road, right behind the dunes. But I think I've had too much. of Long Island. I don't want to do. around in a car all the time. I don’ think it's healthy. But if they see you walking on a road out there, they think you're eccentric.”

Lives Alone

She has lived in Grey Gardens alone ever since her mother died, she said, leading a simple life that includes reading The New York Times every morning, walking on the beach, feeding her five remaining cats as well as the wild. raccoons•that live near her house, sing‐, ing, writing poetry, and preparing, fruits and vegetables for her 5 P.M. meal.

“I went to two cocktail parties last summer to stop the gossip about my being a recluse,” she said evenly, “Most of them looked at me like I was from Mars. I shouldn't have gone; don't drink. If you don't do exactly what everybody else does out there,. if you don't go to the Maidstone Club or join the Garden Club, you're written off as crazy.” •

What will she do after her singing engagement is over. She shrugged. “I'll probably have to rest for five years.” At this point, a friend who was at the rehearsal reminded her that a club in London called Country Cousin had expressed interest in booking her.

A big smile spread across her face. “London,” she said. “I'd really love to go there. London. LONDON. Can you believe it?”

The New York Times/Fred R. Conrad

Edith Bouvier Beale relaxes after rehearsing singing act that opens tonight at.Reno Sweeney: This is my dream, what I've always wanted to do.’

Taken from an excerpt which makes me wonder if Jackie didn't have some ideas in common with her cousin Little Edie in wanting to drop out of the over bearing public view of the public.

Errors in this, not written by me so just leaving them in their original state

Jackie Kennedy with Aristotle Onassis, 1972. (Alain Dejean/Corbis) Forty-five years ago today, Sunday, October 20, 1968, former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy married Greek shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis. Many people still speculate about why she did. Bobby and Jackie Kennedy at a ceremony related to the JFK Library, 1967. Often overlooked in the pondering is the fact that the wedding took place less than five months after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy during his campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. As his sister-in-law Jackie Kennedy had not merely supported his candidacy out of family loyalty but had encouraged him personally as they struggled in the aftermath of President Kennedy’s assassination. Jackie Kennedy after Robert Kennedy’s funeral mass. In the early months of 1964, shortly after her husband was been killed, Jackie had convinced, even pushed Bobby to remain in national politics and “finish what Jack wanted to do,” including withdrawal of the U.S. military presence in Vietnam. The June 5, 1968 assassination of Bobby Kennedy was not only a personal loss for his sister-in-law, but the death of her cautious optimism about the nation’s future. She saw aspects of the culture collapsing into one obsessed with violence and danger. The late president’s widow with her children following her brother-in-law’s funeral service. She began experiencing anxiety attacks about her own safety and that of her children, provoked by the spike in new death threats towards male members of the family and suggested that her seven-year old son, the late President’s namesake, was a logical target. As she had just realized for a second time, even the Secret Service agents provided to escort and watch her young children in their routine lives were no guarantee of protection. A night at the theater meant loud, staring crowds at intermission. (UPI) The huddle of screaming, scrambling paparazzi who stalked Jackie Kennedy and her children might appear to be an amusing novelty to onlookers who randomly encountered it on the streets of New York, but the former First Lady felt it had made her a “freak.” There was nothing flattering or honorific about turning a corner in personal thought or laughter with a friend after lunch to be unpredictably besieged with gnashing cameras and blinded by dozens of rapid camera flashes. The second she emerged from a car or a building, paparazzi were ready to snap Jackie Kennedy. (original photographer unknown).

Mick Jagger and little girl there when JFKjr., sister and cousins vacationed at Montauk at the Andy Warhol compound Eothen (Greek for First Light).

See more on this inside of here.

It's been a long road! The Montauk Connection! Have you seen the Script? JFKjr life and times.

As cited in the Stopsmiling Formerly magazine now currently books. . .

The undulating tide of interest that continues to wash over the work of Albert and David Maysles hit yet another high point in the spectrum of pop culture last spring with the release of HBO Films’ narrative adaptation of Grey Gardens, starring Jessica Lange and Drew Barrymore as Big and Little Edie Beale. The (partly) family-owned-and-operated Maysles Institute followed suit in June with a Grey Gardens festival at their Harlem cinema house, an event to celebrate and re-examine the 1976 cinéma-vérité classic, as well as launch the Grey Gardens book.

The Maysles Institute catches the eye doesn't it?

Similar to A Maysles Scrapbook in form and content, the Grey Gardens book features an endearing hodgepodge of material cobbled together from the Maysles Films archives, which Albert’s daughter Sara writes in the foreword, “had a quality similar to that of the Beales’ own chaotic world. I found garbage bags filled with negatives wrapped tightly in napkins and lined paper, held together by decaying rubber bands, surprisingly neglected and amazingly well-preserved.”

Why is this starting to remind me of Utopia?

The result is a handsome bound tribute to the documentary’s creators and subjects. Photos and transcripts are interspersed with or set within colorful, childlike drawings and collages, and accompanied by a CD of audio excerpts and outtakes. A selection of newspaper clippings includes reviews of the film that regard it as exploitative — along with responses to the New York Times from the Maysles and Edie Beale — shock pieces that reveal the wretched living conditions of Jackie O’s relatives, and society page features that describe the Beales’ public affairs both before and after their manor became the Grey Gardens we all now know.

Whereas the film piles the weird magic of the Big and Little Edie upon us in a linear manner, the Grey Gardens book allows us to pick through it and explore, skipping some parts while dwelling on others. It is a worthy medium through which fans of the film can enjoy and imagine the Beales all over again.

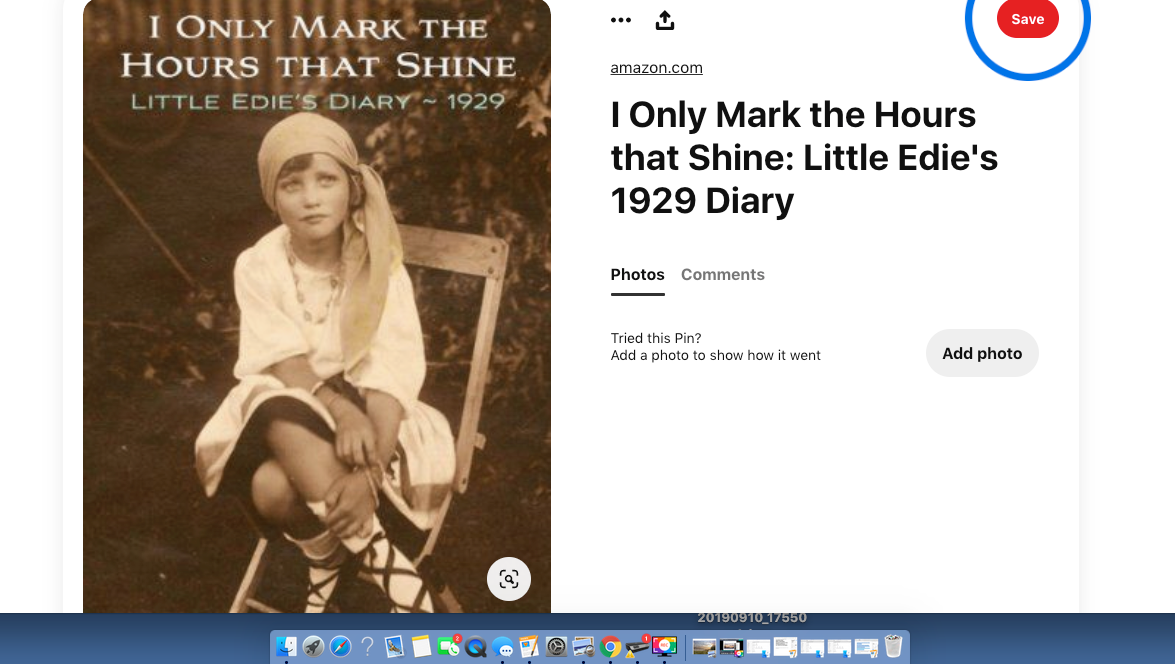

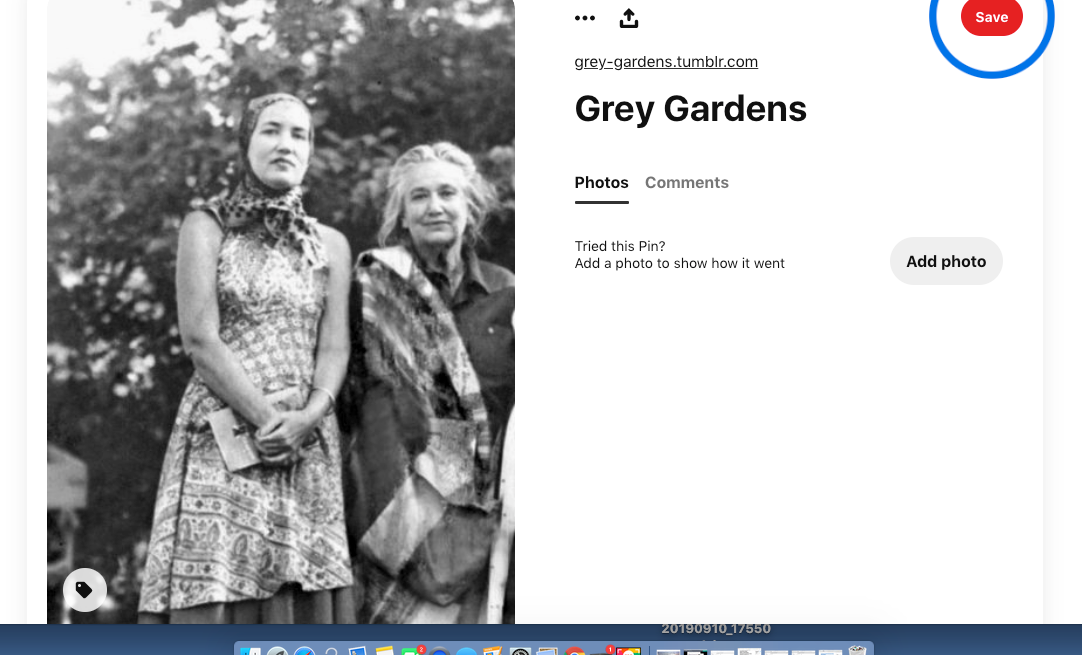

Edith Bouvier Beale (November 7, 1917 – January 14, 2002), nicknamed Little Edie

he had two brothers, Phelan Beale, Jr. and Bouvier Beale, and had a privileged upbringing. Beale attended The Spence School and graduated from Miss Porter's School in 1935.

According to Vanity Fair

Last fall, at Miss Porter’s School, in Farmington, Connecticut—attended by generations of debutantes and heiresses, including Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Gloria Vanderbilt, and Barbara Hutton—a student named Tatum Bass confessed to cheating, and was later expelled. Bass’s parents claim the school allowed their daughter to be so bullied by a group of girls, “the Oprichniki,” that she was driven to cheat. Talking to students, alumnae, and the headmistress, the author discovers that Bass violated a deeper, unspoken code as well.

https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2009/07/miss-porters-school200907

Known as "Little Edie," Beale was a member of the Maidstone Country Club of East Hampton. She had her debut at the Pierre Hotel on New Year's Day 1936. The New York Times reported on the event, where she wore a gown of white net appliqued in silver with a wreath of gardenias in her hair.

While Beale was young, her mother pursued a singing career, hiring an accompanist and playing at small venues and private parties. In the summer of 1931, Phelan Beale separated from his wife, leaving Big Edie, then 35 years old, dependent on the Bouviers for the care of herself and children. In 1946, he finally obtained a divorce, notifying his family by telephone from Mexico.

Edith Ewing Bouvier Beale

Known as Big Edie, she was a sister of John Vernou Bouvier III and an aunt of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

John Vernou Bouvier III was born in East Hampton, New York. His nickname, "Black Jack", referred to his perpetually dark-tanned skin and his flamboyant lifestyle.

Bouvier's great-grandfather, Michel Bouvier, was a French cabinetmaker from Pont-Saint-Esprit, in the southern Provence region. Michel immigrated to Philadelphia in 1815 after fighting in the Napoleonic Wars

In addition to crafting fine furniture, Michel Bouvier had a business distributing firewood. To support that business, he acquired large tracts of forested land, some of which contained a large reserve of coal. Michel further grew his fortune in real estate speculation.

His sons, Eustes, Michel Charles (M.C.), and John V. Bouvier Sr., distinguished themselves in the world of finance on Wall Street. They left their fortunes to their only remaining male Bouvier heir, Major John Vernou Bouvier Jr., who used some of the money to buy an estate known as Lasata in East Hampton, Long Island.

John Vernou Bouvier Jr.

Jackie's grandfather

Jackie's father. . .John Vernou Bouvier III

John Vernou Bouvier III attended Philips Exeter Academy and Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School. He then studied at Columbia College, his father's alma mater, where he played tennis for two years before transferring to the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale University. While attending Yale, he was a member of the Book and Snake secret society and the Cloister Club. He graduated in 1914.

Upon his graduation,

- Also known as Black Jack Bouvier, brother to Big Edie

- he went to work as a stockbroker at his father and uncle's firm: Bouvier, Bouvier & Bouvier

- In 1917, he left the firm to join the United States Navy

- he transferred to the United States Army, where he served as a major

- Bouvier was discharged in 1919

- he went back to work as a stockbroker on Wall Street

- Auchincloss was responsible for getting Jacqueline Bouvier her first job in journalism at the Washington Times-Herald

- a member of the Burning Tree Club and the Metropolitan Club

Bouvier married Janet Norton Lee (Jackie and Lee's mom), the daughter of real estate developer James T. Lee in 1928.

Bouvier's drinking, gambling, and philandering led to the couple's divorce in June 1940. Bouvier never remarried.

In June 1942, Janet Lee Bouvier married Hugh Dudley Auchincloss, Jr. Janet reportedly did not want her ex-husband to escort his daughter, Jacqueline, down the aisle for her 1953 wedding to John F. Kennedy, so Jacqueline was instead escorted by her step-father. However, some reports indicated Bouvier was too intoxicated to escort his daughter, leading Auchincloss to step in to give the bride away.

Looks like Jackie would have been around 11 years old when her parents divorced then 13 years old when her mother married her stepfather.

History of Jackie's stepfather, Hugh Dudley Auchincloss, Jr.

- From 1924 to 1926, Auchincloss practiced law in New York City

- before joining the Commerce Department as a special agent in aeronautics.

- In 1927, he was appointed an aviation expert in the State Department.

- Four years later in 1931, he resigned government service to form a brokerage firm

- During World War II Auchincloss worked for the Office of Naval Intelligence and the War Department and was commissioned with the rank of Lieutenant in the Naval Reserve on May 26, 1942, serving in the United States Navy during World War II.

- was once married to a Russian noblewoman.

- In 1935, he married Nina S. Vidal, the only daughter of Senator Thomas Gore.

The Gore family was one of the nineteen original families that owned farmlands in what later became the capital of the United States, the District of Columbia.

When the District was established in 1790, the families that had been dispossessed to make way for the capital city, including the Gores, reaped significant financial rewards. The Gores who remained either sold their land in lots, built homes or hotels, and all became rich. The Gores that moved away, including the branch of Thomas Pryor Gore, moved to the far West, which in those days was Mississippi.

In 1931, he bought his seat on the New York Stock Exchange for $235,000 (equivalent to $3,951,000 in 2019). It was reported that he used some of the large inheritance received from his mother to found the Washington, DC brokerage firm of "Auchincloss, Parker & Redpath" with Chauncey B. Parker and Albert G. Redpath.

The firm eventually had 16 offices with two in New York City and the rest spread along the East Coast. In 1970, the firm merged with Thomson & McKinnon, a brokerage house based in New York. At the time of the merger, the new firm, known as Thomson & McKinnon Auchincloss, had assets of $160 million (equivalent to $718,877,000 in 2019) and 58 offices.

In New York Magazine,

The seeds of their tale go back to 1915 when the family first discovered, beyond “dressy” Southampton, a “simple” summer resort composed of saltbox houses and village greens. The sea was still tucked then behind great cushions of sand dunes. Behind them potato fields stretched in white-tufted rows clear to the horizon like a natural Nettle Creek bedspread. Right from the start, East Hampton provided a refuge for the family’s scandals and divorces and all manner of idiosyncrasies common to those of high breeding.

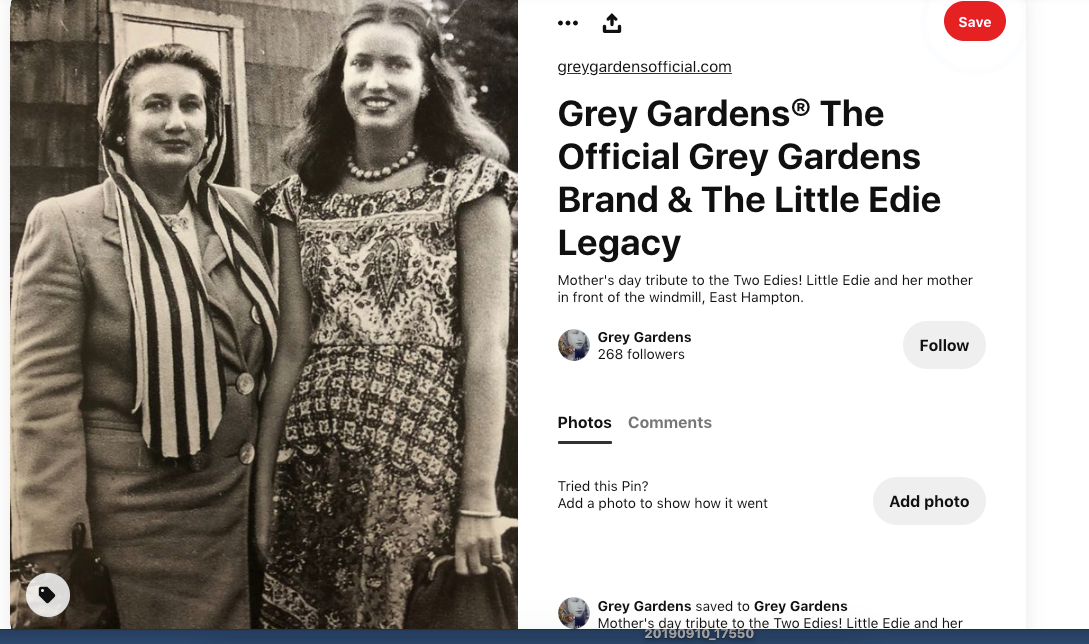

The family brought the wealth of Wall Street to this simple resort. It casually purchased a cabana at the Maid-stone Club for $8,000 in 1926. The men set down roots in four houses and sired beautiful women. In due time the little girls’ names entered the Social Register. Later they would appear in the creamy pages of The So-cial Spectator… “Seen at the recent East Hampton Village Fair, ‘Little Edie’ Beale,” under the picture of a full-lipped blonde shamelessly vamping through the brim of her beach hat, or, “Picking up another blue rib-bon at the East Hampton horse show, Miss Jacqueline Bouvier with her father, John Vernou Bouvier III cap-tions which reflected the infinite self-confidence of the indomitably rich.

The Social Spectator described an era which will never be again. The family’s homes are gone now, all but one. And the family itself, after 300 years, has slipped back into the abominable middle class. All except a few. One became the most celebrated woman in the world, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis. Two others never gave a damn about all that. They rebelled against the Maidstone, shunned garden parties to pursue the artistic life. Now, passed over by history, they are left to the wreck of their house.

Contemporary East Hampton is caught up in a war of land values. It is no longer a refuge for artists and eccen-trics. The dropouts at the foot of the lane do not conform to the new values exhibited by “beach houses” with elevators. Their lives are remote from the Friday afternoon helicopters which ferry high-powered businessmen out from the city and drop them into pastel sports cars on D. Blinken’s lawn. Around the corner from them, on West End, a parade of tycoons’ castles, one owned by Revlon’s Charles Revson (who copied the house next door), ends in a nest of five mansionettes owned by Pan Am’s Juan Trippe and family. But the grounds belong-ing to the dropouts bear no resemblance to putting-green lawns, nor to the wedding-cake trees created by topiary gardening on estates which retreat from them behind trimmed privet hedges. These two have lived beyond their time at the juncture of Lily Pond Lane and West End, where the privet runs wild over a house called Grey Gardens.

One Sunday morning’s discovery changed all that. My daughter came running, tearful, holding three baby rab-bits in a Tide box. She had found them motherless by the side of the road. “Can’t we take them home?” she asked. I explained they would never survive the train ride. She had another idea: if the Witch House had all those cats, whoever lived there must like animals. Before I could protest, we had ducked under the hedge, skittered past a 1937 Cadillac brooding in the tangled grasses, and we were deep into the preserve of twelve devil-eyed cats. There was no turning back.

“Mother?”

We whirled at the sound of an alien voice. She was coming through the catalpa trees as a taxi pulled away, and she was covered everywhere except for her face, which was beautiful. “Are you looking for Mother, too?” she asked, more unnerved than we.

My little girl held out the Tide box to show her the trembling bunnies.

“Did you think we care for animals here?” The woman smiled and bent down close to the face of the child, who silently considered her. This was not at all a proper witch. She looked sweet sixteen going on 30-odd and had carefully applied lipstick, eyeliner and powder to her faintly freckled face. The child nodded solemnly: “This is an animal house.”

“You see! Children sense it.” The woman clapped her hands in delight. “The old people don’t like us. They think I’m crazy. The Bouviers don’t like me at all, Mother says. But the children understand.”

My little girl said it must be fun to live in a house where you never have to clean up.

“Oh, Mother thinks it’s artistic this way, like a Frank Lloyd Wright house. Don’t you love the overgrown Louisiana Bayou look?”

My daughter nodded vigorously. At this point the woman looked shyly up to include me in the conversation. “Where do you come from?”

“Across the way.”

“My goodness, it’s about time we got together! How many years have you been here?” She rushed on before I could answer, as though reviving a numb habit of social conversation and desperate not to lose the knack. “You phone me. Beale. That’s the name, Edith Beale.”

As she swept past us in a long trench coat and sandals, her head wrapped in a silk scarf knotted at the back of the neck, I could have sworn she was—who? I’d seen her picture hundreds of times.

Edie Beale, safe on her porch, pointed out the formally lettered sign she had made for the front door: Do Not Trespass, Police on the Place.

“Are there really?” my daughter breathed.

“Not really, but Mother is frightened of anyone who comes by.” She then described a neighbor who tries to club the cats to death at night, and the boys from across the street whose surfer friends try to break in. I suggested the boys might just be prankish.

“Jackie?”

“I’m Jacqueline Bouvier’s first cousin. Mother is her aunt. Did you know that?”

“No, we didn’t.”

“Oh yes, we’re all descended from fourteenth-century French kings. Now a relative has written a book saying it’s all a lie, that we don’t really have royal blood. He’s a professor, John H. Davis, and he’s break-ing with history. Everyone is. That’s how I know the millennium is coming. The Bouviers: Portrait of an American Family. Not a bad book really.”

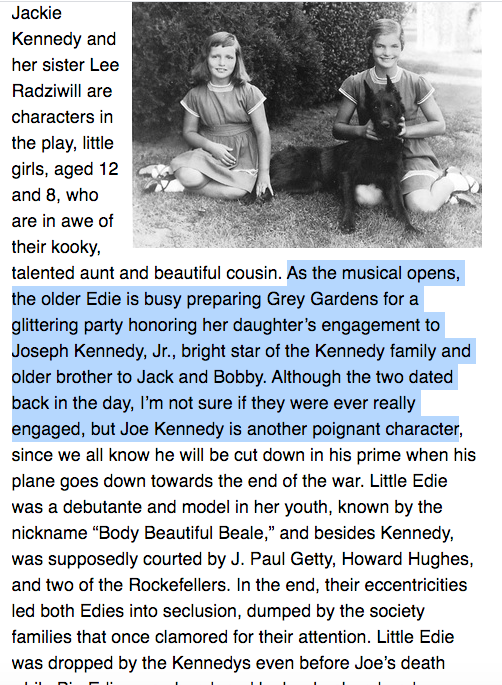

(Subsequently, I read the Davis book and was struck by the parallel courses of their two lives—Little Edie, better known as Body Beautiful Beale, but so breakable; her young cousin Jackie, whose heart developed a steel safety catch—until an accident of fate drove one to the top and condemned the other to obscurity. It came out in the inauguration scene:

“The Reception for Members of President and Mrs. Kennedy’s Families” was the first Kennedy party held in the White House. Peter Lawford and Ted Kennedy showed up. Little Edie Beale approached J. P. Kennedy, who was looking his usual unassuming self, and reminded him jokingly that she had once almost been engaged to his first-born son, Joe, Jr. And if he had lived, she probably would have married him and he would have be-come President instead of Jack and she would have become First Lady instead of Jackie! J. P. Kennedy smiled and took another drink.)

“I’ve just come from church, which put the millennium in my mind,” the lady of Grey Gardens was saying. The woman before me, a version of Jackie coming from church on a Greek island, was Little Edie in the summer of her 54th year!

“You…resemble your cousin,” I faltered.

“Mmmm, Jackie had a very hard time. Did you like the Kennedys?” She didn’t skip a beat. “They brought such art to the country! Besides the clothes and makeup, politics is the most exciting thing about America. Didn’t you think the Kennedys would be around forever—at least three terms?” Her eyes danced.

My daughter wanted to know if she knew President Kennedy well.

“Jack never liked society girls, he only dated showgirls,” she began, synchronizing only with her memories. “I tried to show him I’d broken with society, I was a dancer. But Jack never gave me a tumble. Then I met Joe Jr. at a Princeton dance, and oh my!” She swooned. “Joe was the most wonderful person in the world. There will never be another man like him.”

“But you were a ballerina?” My daughter wanted to stick to the facts.

“What, sweetheart?” Edie Beale was off in her private world again; this brought her back. “Oh yes, I started in ballet. Ran away from home three times. First to Palm Beach; everyone thought I’d eloped with Bruce Cabot, the movie actor—I didn’t even know him! I never did anything but flirt—you know, the Southern belle. My father brought me back. He’d always thought my mother was crazy because she was an artist. Then I went into interpretive dancing and ran away to New York. Mother caught me moving out of the Barbizon, she thought it was the correct spot. But I moved into New York’s oldest theatrical hotel. On the sly a friend sent me to Max Gordon. The minute he saw me he said: ‘You’re a musical comedienne.’ I said, ‘That’s funny, I did Shakespearean tragedy at Spence.’ Max Gordon said the two were very close. I was all set to audition for the Theatre Guild that summer. Shaking with fear, you can imagine with my father still alive—he’d left Mother for the very same thing! I modeled for Bachrach while I was waiting for the summer to audition. Someone squealed to my father. Do you know, he marched up Madison Avenue and saw my picture and put his fist right through Mr. Bachrach’s window?”

At that, Little Edie threw back her head and giggled so contagiously we caught it ourselves. “But”—we were gasping for the end of the story—“did you ever go for the audition?”

“Oh no. Mother got the cats. That’s when she brought me down from New York to take care of them.”

It was a stunning non sequitur, but the empty finality of her voice made the meaning clear. We had come to the dead end of a human life.

Then an operatic voice sang its lament through the upstairs window.

EeeDIE? I’m about to die.

“Oh dear, Mother’s furious because she’s not getting attention. I’ll be right up, Mother.”

“The bunnies.” My daughter offered the Tide box.

“They are sweet, but you see, Mother runs everything around here. I work for her and she might throw me out….” Little Edie accepted the bunnies anyway. She walked us up to the catalpa trees. Suddenly she gasped, shrank back:

“Oh dear, it’s fall.”

We followed her eyes to the ground where a dead mouse lay in our path. “That’s the sign of an early fall. There’s evil ahead,” she said.

It was not an early fall. But Edith Beale was right about evil in the wings. Late August Saturdays still found the new rich along the Gold Coast entertaining the “fun people” in lime pants from Southampton. At high noon they sat beside gelid pools exercising little but their mouths; talking business, nibbling quiche, complaining about neighbors who drive down the land values.

These are the city people who send out their architects to order the shoulders of the sea broken, crushed, swept back into the potato fields. On the leveled stage they set down their implausible houses and bathwater pools. New dune grass eventually appears in patches, row on row, like hair transplants. But dunes never grow back. The new people use the sea only as a backdrop (“You don’t swim in it, do you?”), insulting it, hating it really. The wind wrecks their hairdos. Sand nicks their glass window walls. They use the sand only as a mine field to hide the wires leading to their Baroque burglar alarm systems.

So long as real-estate moguls and barons of Wall Street and their shrill, competitive wives keep coming out from the city to erect display cases on the dunes, the Village Fathers will appease them. The new people create jobs and pay obscene beachfront taxes. Nothing is likely to be said aloud about what they violate of East Hampton. But when a few of them complain about those two living in an “eyesore” near their precious land values, the Village Fathers can be very quickly turned into a posse. Even as Labor Day approached, such a posse was being assembled against the Beales.

The sea comes into its wild season with September riptides. Gathering far out, it hurls its weight against the land, smearing the beach with tidal pools, while opposing waves tear at virgin sand and drag it back. Most people in East End stay away from the beach then.

Who was that lone figure in black?

Both Sundays after Labor Day she ran off the dunes like an escapee and plunged into the surf. Alarmed at first, I watched her draw the water hungrily around her. But she was a strong swimmer, a child-woman of such unspent exuberance. Her body was still beautiful, I thought, as Edith Beale came up the beach in a black net bathing suit.

“I haven’t seen you in so long!” she called. “Mother never allows me to show myself on the beach after summer, but this fall I had to come out.”

I said she still looked like a model.

“Shall I tell you what I’ve done for twenty years? Fed cats. Mother wouldn’t let me go around with American men, they were too rich and fast. She was afraid I’d get married. Nothing has happened in twenty years, so I haven’t changed in any way.”

She remembered every detail from our last encounter. How was my trip to Russia? she asked. How are dancers treated there?

“The simple life is not understood in America,” she broke in with a deep whisper. “They’re all so rich and spoiled. I would have loved this life, except—I never got to say goodbye to any of my friends.” She blushed to the edges of her flowered cap, admitting she had always preferred older men. “They’re all dead now and I’m alone….”

We walked toward the sea, which seemed to revive her spirits. “So I had to make friends with the younger generation,” the voice lilting now, “the boys who come by and like the overgrown look. We sketch together.” She turned quickly and scanned the beach. “Maybe they thought I was getting too friendly with the young boys.”

They?

Her eyes focused on a dark blur, maybe a mile away. She recounted a strange phone call from one of her brother’s sons last February: You’re in the soup, he kept saying, the County’s going to take your house. “I’m psychic and I feel it coming.”

That was her brother coming now, in the jeep down the beach; she grew stiff and asked me to stay and meet him. I wondered which brother it would be, having read of the contrast between them. While Little Edie confounded her Bouvier relatives by imitating her mother’s rebellion against bourgeois conformity, her younger brother, Bouvier Beale, was following in the footsteps of his lawyer father and grandfather. He married a society girl and established his own law firm in New York—Walker, Beale, Wainwright and Wolf. Today he lives in Glen Cove, belongs to Piping Rock, as did his grandfather, and only last summer built his own summer home in Bridgehampton. The other brother, Phelan Jr., escaped to Oklahoma and never came back.

But why hadn’t they come to the rescue of their 76-year-old recluse mother and pathetic sister buried alive in Grey Gardens? Edith Beale must have read my thoughts.

“Now my brothers, they’re great successes. But the way they’ve been acting has put Mother more on my neck than ever. They refuse to give one penny to the house. The trust from my grandfather is about gone. Mother suffered reverses in the stock market last year, so my brothers sold her blue chip stock.”

I asked a sensitive question about her present financial situation.

“Oh we’re not destitute, Mother has collateral. It’s been my life’s work to protect her collections, we don’t trust anybody.” The rest was hurriedly whispered: “My brother, Bouvier Beale, has been after Mother for a year now to sign over power of attorney. I think he wants to take over the house and put poor Mother into an institution. He treats her just as her father did, you know, because she’s an artist. It all goes back to Mother deciding she wanted to sing…she was so advanced. Grandfather threatened to disown her but she made plenty of appearances in clubs around New York. She is still totally modern and correct in everything, with one exception. My career.”

But how could Mother deny her the very freedom of expression for which she had defied an entire family? I pressed.

“Two women can’t live together for twenty years without some jealousy,” Little Edie Beale said reluctantly. “Not that my voice is better than Mother’s, but she can’t dance.”

The jeep was upon us. Its driver, a stiffly formal man, was introduced as Bouvier Beale. Seemingly embarrassed, he walked off with his sister for a private conference. As I climbed the dunes, their bodies were turning rigid in dispute, necks stiff. A shout came back in a man’s voice: “You must go to a room in the Village!”

Little Edie broke away and ran for the sea.

October begins the bad months. When summer finishes with East Hampton and black ice begins to form, the stupid puddle ducks freeze in the Village pond and the caretakers stay drunk, and besides family fights and in-breeding there is very little to do. The Village Fathers had cut out their work in advance. The new Village building inspector, A. Victor Amann, had sent a letter to the Beales back last February, demanding the overgrowth be cut back: the Village would do it for $5,000. He sent a copy to the trust fund, which replied there was no money left. Another letter from P. C. Schenck’s fuel company of East Hampton warned the Beales their furnace was unsafe. A copy of that was mailed to Bouvier Beale, along with his mother’s unpaid bill of $800.

Ignored, the Village Fathers moved in on October 20. Little Edie was on the porch of Grey Gardens when five people materialized. She thought they were wearing costumes, she told me. One said: “You have no heat.” Another said: “You have no food.” A public nurse said: “You’re sick.”

“Mother, did you hear that? This horrible public health nurse says we’re sick!” Little Edie stamped her feet furiously, informing her invaders: “We’re Christian Scientists. The only medicine is work.” Mother’s voice boomed from the window: SEND that nurse AWAY—SHE’S been in contact with ALL the GERMS of SUFFOLK COUNTY!

The invaders retreated, but only to assemble a proper posse (which took all of two days). East Hampton’s Mayor Rioux was away on vacation and his deputy, Dr. William Abel, was determined to have done with the misfits.

“People are basically no damned good,” the Acting Mayor later expressed himself to me. I thought this odd coming from a chief surgeon at Southhampton Hospital, but Dr. Abel added, “I prefer animals.” The very mention of the Beale house caused him to grip his knees and go white: “The house is unfit for human habitation—animals don’t live like this. The two sweet old things won’t move unless they are forcibly moved because, un-fortunately, they’re not mentally competent.” He declined to go into the reasons for his diagnosis because “I get so wrapped up in it.” But as a public official he felt it his duty to leave me with a warning. “Are you aware that many of the most horrible murders in our country are committed by schizophrenics who appeared perfectly stable, maybe even saner than I?”

In an unusual move, the Village sought help from the County. On the 22nd of October a raiding party of twelve made its move. County sanitarians, detectives, and ASPCA representatives from New York forced their way past the ladies of Grey Gardens armed with a search warrant issued by a Town Justice on the ground that the Beales were harboring diseased cats. Cameras recorded the sorry scene: cat manure covering the floors; a five-foot-high mound of empty cans in the dining room; the Sterno stove on Mother’s bed; cobwebs, cats and all sorts of juicy building-code violations. Mother thought it was a stickup. The sanitarians had the dry heaves. It remained for the ASPCA man, alone, to report he’d seen human fecal matter in the upstairs bedroom.

“They never said why it was they’d come,” Little Edie told The East Hampton Star.

Sidney Beckwith, of the County Health Department, got on the phone with Bouvier Beale and quoted the hot report of his inspection.

“Mr. Beckwith, you’ve described it very well, but it’s nothing new—Mother is the original hippie,” said Bouvier Beale. Astonished that such a prominent family would sit back and let their relations be condemned, Mr. Beckwith warned that the next inspection would create a national scandal.

“If that’s what it takes to get Mother out of the house, sobeit,” said Beale.

It was never clear after the whole mess hit the newspapers, a month later, who had put whom up to what. But three forces conspired to finish off the ladies of Grey Gardens: Village Fathers, a few nameless neighbors, and their closest kin. My first clue to their plight was a New York Post headline of November 20:

JACKIE’S AUNT TOLD: CLEAN UP MANSION

I called immediately but the Beales’ phone was “out of order.” There was nothing to do but drive out to Grey Gardens. Stripped of summer foliage, it stood naked to prying eyes.

Shades of Chappaquiddick. Five girls from Huntington sat in a car across the street, trading binoculars: “We’ve been here all day.” An old local jumped out of his station wagon, armed with an Instamatic, and posed his niece before the pariahs’ house. “Sure, I knew old Black Jack Bouvier, used to caddy for him up the Maidstone,” the old man said. “Knew the Beales too, delivered a lot of packages up here.”

But wasn’t he horrified at this invasion of their privacy? “We swim in different schools. I don’t have much in common with the Beales,” he said. “I’m a local working person.”

At dawn the following day I reached young Edie Beale by phone. She was terrified, but adamant: “Mother would never be put out of this house. She’s going to roof it, plaster it, paint it, and sell it. We’re artists against the bureaucrats. Mother’s French operetta. I dance, I write poetry, I sketch. But that doesn’t mean we’re crazy or taking heroin or anything! Please—” her voice pleaded for all she was worth—“please tell them what we are.”

In the early twenties “Big Edie”—sister of Black Jack Bouvier (Jackie’s father), wife of lawyer Phelan Beale, and mother of Little Edie—became the first lady of Grey Gardens. It was a proper 28-room mansion when they bought it. The box hedges surrounding it were trimmed. But even then a mantle of ivy draped its gables and the lush walled-in garden to one side suited Big Edie’s unconventional personality.

By 1925 her husband was prospering. Her children, Little Edie, Phelan Jr. and Bouvier, were small. But Edie had a retinue of servants that freed her to cultivate interests and opinions which the Bouviers considered downright subversive. She played the grand piano in her living room by the hour and sang, in her rich mezzo so-prano, “Indian Love Call” and “Begin the Beguine” to a husband who was generally upstairs hollering for his tuxedo to be pressed. He’d go off to stuffy cocktail parties and Maidstone dances which bored her to tears. Since she was likely to wear a sweater over her evening gown and discuss Christian Science, the family became less and less insistent that Big Edie come along.

Big Edie’s two brothers were then in fierce competition to become rich men. Before they reached 35, Black Jack Bouvier had reaped a fortune of $750,000 on Wall Street, while Bud Bouvier made his money in the Texas oil fields Jack was always one up on his brother, which drove Bud to destroy his marriage and caused the first Bouvier divorce in 100 years. In 1929, the same year that the beautiful Jacqueline was born to Black Jack, his brother drank himself to death.

Material success had become the real Bouvier god, as it was for so many others of that wildly prosperous era. Only Big Edie, among the Bouviers, dropped away from bourgeois conventions. Her brother’s demise foreshadowed the family’s deterioration. Within two weeks of Bud’s death, and with the entire clan at the peak of its fortunes, the stock market crashed.

Black Friday found the old family broker, M. C. Bouvier, at his office at 20 Broad, congratulating himself on his cash reserves and the quality of his bonds.

Black Jack was much less serene. He was forced to ask for help from his father-in-law. James T. Lee agreed on the condition Black Jack curb his flamboyant lifestyle—Jackie’s father was fatally susceptible to beautiful women and big money, which he spent faster than he earned. It was a great humiliation to move his wife and Jacqueline to a rent-free apartment, provided by his father-in-law, at 740 Park Avenue. By 1935 his net worth had plummeted to $106,444.

The family’s lot began to improve only when M. C. Bouvier died in 1935, leaving his brokerage firm to Black Jack, and his fortune to Major Bouvier, who became the family patriarch. But as for Big Edie, her husband had left her in Grey Gardens and disappeared into the Northwest woods, where he built his own hunting lodge, Grey Goose Gun Club. He sent only child support. Big Edie became dependent on her father, Major Bouvier, for a subsistence of $3,500 a year, and began to withdraw into seclusion.

The Bouviers lived their golden East Hampton summers through the thirties and forties, seemingly exempt from the country’s economic despair. Ignoring Depression and war, they divided their time between the Maidstone Club and Lasata, Major Bouvier’s great house on Further Lane. But the Major’s flamboyant reign was accomplished at a gruesome price, to be paid much later by his heirs. By living off principal, he assured the family comfort and style only for as long as he lived.

But for the moment, his grandchildren were dazzling the cabana owners of the Maidstone. The Bouvier who attracted all the stares as she sauntered down the midway was Little Edie. The Body Beautiful at 24. Her cousin Jackie was a solemn twelve and generally in jodhpurs. About the contrast Black Jack was fiercely defensive. During luncheons at Lasata he would announce to the family: “Jackie’s got every boy at the club after her, and the kid’s only twelve!” Everyone knew Little Edie was It, but her mother never rose to the bait. Big Edie was always busy directing the attention to herself. The excuse might be Albert Herter’s portrait of her in a blue dress, done twenty years before. “Did you know the blue dress in that painting is the same one I’m wearing now?” She would pause for effect. “That’s how poor I am.”

Blue Dress Symbolism?

Black Jack would remind her that a clever woman would have gotten some alimony out of her husband. Big Edie would remind her family that she was not a golddigger. Whereupon she would head for the piano with ten adoring children traipsing at her heels.

The last of the fashionable family affairs was the 1942 wedding of Big Edie’s son, Bouvier Beale. A ceremony at St. James’s was scheduled for four, and almost the entire Bouvier family was in place. Big Edith was the missing guest. The wedding was half over when she arrived, dressed like an opera star. The bride and groom took the incident in stride, but Major Bouvier had had his fill of Edith’s outlandish behavior. Two days later he cut her out of his will. From then until his death in 1948, the moralizing Major used his changing will as a club, but Edie had already become the recluse of Grey Gardens when the news came that her share of the dead Major’s dwindled fortune was a $65,000 trust fund, her sons in control.

On that sum, Big and Little Edie have lived for the past 23 years. Little Edie always talked about getting away… “I’ve got to get out of East Hampton, fast,” she told her neighbor, Barbara Mahoney. That was sixteen years ago, when she crossed the street to take her a friendship card with a red sachet: Thank you, Barbara, for being my friend, it read. “You know,” she whimpered, “I’m 38 and I’m an old maid. I don’t have any friends. Ought to get away. I don’t know where to go!”

About that time the ladies of Grey Gardens met Tex Logan in Montauk. He was playing steel guitar and looking for jobs. “He was mad about my mother,” Little Edie recalls, “so you know, he came in as a carpenter-maintenance man-cook. Tex did just about everything for nine years, on and off.” But Tex was a wanderer. When he grew bored, he’d hitchhike out of town and when he came back he was inevitably drunk. Then there was the night Tex was arrested for possession of a pistol at Mrs. Morgan Belmont’s bridge party. The East Hampton Star gave the Beale house as his address. How the ladies of Grey Gardens did fuss! Tex didn’t come back again until the winter he contracted pneumonia. He was found a week later, dead, in the kitchen of Grey Gardens. This time The East Hampton Star noted, discreetly, the man was the Beales’ “caretaker.”

“We never let anybody in here after that,” Little Edie recalled, “because the house is loaded with valuables. Except once, in the early spring of ’68, when the Wainwrights invited Mother and me to a big dance. Mother said we should make one last appearance before the Old Guard of East Hampton. I was so excited—but Mother said, ‘You are absolutely not going to that dance unless you get somebody to help clean up this mess.’”

Little Edie hired two boys, sons of old natives, who were home from the Navy. She noticed they were acting funny on the second floor, but in her excitement she ignored it. The party was being given by young Edie’s childhood friend, Carolyn Wainwright, for her daughter’s debut. The reclusive Beales made a breathtaking entrance.

Mother wore a wrapper open to the waist and clasped with a dazzling brooch. In her hair, which looked as though it hadn’t seen a comb in years, she had wound faded silk violets. Little Edie arrived desperate to dance, trailing a black net stole over her black bathing suit and fishnet tights.

Edie danced by herself with one red rose. Somebody’s sympathetic husband got up to dance with her, but she was inexhaustible. The rock music grew wild and Little Edie even wilder—“I flew into a jungle rock and nobody could control me, not even Mother!” Late in the evening, Big Edie dragged her wayward daughter home, scolding all the way: her disgraceful behavior would release evil spirits, just wait. They entered Grey Gardens to find $15,000 worth of heirlooms stolen.

Last August the Beales paid $1,790 in taxes to the Village of East Hampton for one more year in the life of Grey Gardens. “Why are my brothers so anxious to get Mother out?” Little Edie kept asking. “She was going to sell the house anyway, before the taxes are due next August. She’s just a little superstitious. Mother thinks if she makes a will, she’ll die.”

Meanwhile a Village official was calculating out loud: “It would take about $10,000 to demolish the house. With the land cleared you could easily get $80,000, a sum that would be of considerable interest to members of the family…” Other estimates run as high as $300,000.

“The final degradation for Grey Gardens,” moaned Edith Beale.

When the raids began, the Beales decided the Village was out to break them. “I don’t think we can live in America any more,” sighed Little Edie. “The only freedom we have left is the press. Thank God I could tell my side of the story to The East Hampton Star. Isn’t it a terrific paper; it’s our Daily News!”

Meanwhile the international press was having a field day with the sordid tale—“they keep saying we’re old and ill and have to be institutionalized,” Little Edie wept to her lawyer, Mr. LaGattuta from The Springs. “I don’t look old, do I?” But Mother felt she was smarter than any lawyer and refused to pay LaGattuta a fee.

After a third inspection on December 7, Mr. Beckwith informed the Beales by letter: “Should you continue liv-ing in this dwelling under the existing conditions, this department will have no recourse but to take action to remove you.” That action would be an eviction hearing immediately after Christmas. Mr. Beckwith took the liberty of sending a copy to Mrs. Onassis with a personal note, mentioning that her aunt and cousin had spoken fondly of Jackie and if she could do anything to help, the Beales certainly needed it. Although Mrs. Onassis was in New York partying all month, she made no effort to contact her brutalized relatives. Her social secretary, Nancy Tuckerman, insisted that Mrs. Onassis was always very fond of them, too. In her opinion, however, it was not a matter of money but of how they chose to live.

The last time I saw Little Edie was the week before Christmas, when she invited us out to take pictures. Pre-pared as though for her stage debut, garbed in black net and flashy reds and heavily perfumed, she swept out the door in grand theatrical tradition.

EeeDIE! WEAR YOUR MINK! a voice called to her.

“Mother always tells me how to dress,” she exclaimed, returning with a bottle of frosted fuchsia nail polish and a mangy fur jacket. When we had finished, she invited us in. “What can they possibly have against this house? They haven’t seen the inside.”

She led us into the narrow damp hall and up the lightless staircase, pointing out the carved banister and paneled doors…“These are very much in demand these days.” Animals hid still as stone in the gloomy deeps until we passed; suddenly dust would scatter and…something leapt past our heads—a bat, no, a cat—flying to some ceiling perch. The windows at the top of the stairs were blinded with cobwebs and pawing vines, the bittersweet vines of Grey Gardens grown thick as boa constrictors. Mother had set out some crackers and Taylor’s port for our refreshment. Little Edie poured. “Only students of architecture can fully appreciate this place,” she said. Her performance was exquisite. We scarcely noticed a cat eating his own droppings in one corner. We were completely entranced by this bizarre version of a White House tour led by Jackie Kennedy.

Mother kept wheezing inside and banging on the floor. “She’s furious because I’m getting all the attention,” confided Little Edie. Would Mother like her picture taken? we ventured. “You don’t want your picture, do you, Mother?” she called out. And then to us, in a theatrical aside, “Mother looks like she’s about to die.”

I AM. I’M GOING TO DIE TODAY!

“You see?”

EeeDIE? My MAKEUP is under the BED.

“Never mind, Mother.”

We reminded Edie of a beautiful girl whose picture ran 30 years ago in The Social Spectator, Little Edie Beale at the East Hampton Fair.

“I hate it when people say I was beautiful in the old days,” she grimaced. “I want to detach myself from the past! Do you understand? I like to think I’m good now. I’m terrific now!”

But what does she do here for twelve hours of every day? We asked the second lady of Grey Gardens.

“I wake up and write poetry, like other people have coffee. I love the late movies on TV.”

And in between?

Something snapped in Little Edie at that moment. Her mask dropped and she whispered with urgency of a child:

“I’ve been a subterranean prisoner here for twenty years. If you only knew how I’ve loathed East Hampton, but I love Mother….they must have found out how I hated this house. They must have heard my scream.”

What scream?

“Last summer, out that broken window, when I screamed at Mother for the first time—‘It’s boring, boring, boring here! I’ll go anywhere to be free!’.”

This was the Secret of Grey Gardens—the unfinished woman who stood before us, consumed by cats, fed upon for decades by her broken mother, was far from buried in Grey Gardens. She was only now ready to live! Her family has disintegrated, the survivors have turned away, preferring scandal to parting with a sou from their fortunes to ameliorate this shame. There is nothing left now, nothing, but the hope in Little Edie’s wound-shattering scream.

As we backed toward the car her lower lip trembled. She came running to the edge of the catalpa trees and cried out: “Call me anything, but don’t call me old!”

I found this very interesting taken from dannymiller.typepad blog

See more in sources below.

More Sources, connecting articles and reports

https://nymag.com/news/features/56102/

https://dannymiller.typepad.com/blog/2006/09/before_madness.html

http://mygreygardens.com/gpage22.html

@artistiquejewels/notes-on-ze-plane-ze-plane-coming-back-in-to-finish