It seems that, by chance of fate, the most important things for man are usually underestimated, and it is not for nothing, because while something is more important, it becomes more common, and when normalizing, the illusion is created that this essential thing does not have any value.

Something like this happens with language, which, because it is of such vital importance for our communication with our peers, therefore for our association, becomes so common that the delicacy and importance of this precious instrument is often forgotten.

The simple fact of speaking a common language already makes us largely share a vision with our peers, since such vision is necessary to create and maintain the language, however, the way in which we use such a magnificent instrument makes us in turn have a different personal perception from the rest, by conceptualizing the world in a unique way.

The language barrier, the regional dialect, and the grammar can be such determining factors that sometimes you can read the same words that I am writing, and give you a meaning that I would never have thought of. This has to do with the characteristic subjectivity of man, which is influenced by numerous ideal factors that interfere in his perception with the world, such as culture, beliefs, and of course, of which I will speak today; the language.

One of the things that I have noticed during my time in a multilingual, multicultural, and international community like Steemit, is about the great power that languages have in shaping the perception of people, it is not necessary to be very smart to notice this, but it is thanks to Steemit that I have been able to verify in a personal way the differences generated by language when it comes to perceiving, understanding, and expressing information.

I am a native Spanish speaker, therefore, I speak one of the so-called Romance or Latin languages, unlike the English in which I refer to you currently, which is a hybrid between Germanic and Latin languages, with an obviously Germanic preponderance. If you have communicated with people of other languages similar to yours, you will notice that among the languages of the same (sub)family, the communication is much more fluid, for example, it is easier for a German, Norwegian or Swedish to speak English than for a Russian, Chinese or Spanish. In the same way, it is easier for a Spaniard to speak Portuguese, Italian or French, than for a German, Croatian or Japanese.

This is because the roots of their words have the same origin; for example, the Latin word "lībertās", evolved to "libertad" (Spanish), "liberdade" (Portuguese) "liberté" (French), "libertà" (Italian), and its similar (though not equivalent) Germanic, from the root "frij-", evolved to "frihet" (Norwegian and Swedish) and "freiheit*" (German).

But English, which is a Germanic-Latin hybrid, took "liberty" from Latin and "freedom" from Old English. While this might seem redundant and nonsense, because they would be two words with the same meaning, the reality is that when a language adopts a foreign word, it adopts a new conception in turn, because these different languages don't have the same connotation for the word, they only maintain some similarities between them. Although today both words are misused as synonyms, making the action really nonsense, the meaning of both words is not the same.

Let me then explain the differences between the two words, without forgetting to mention that I am not a linguistic scholar at all, and my knowledge of English is not even high, and the differences that I mention below are simply works of my observation, taking into account the origin of both words, for which I endowed with a lot of information.

Freedom vs Liberty

The word "freedom" in the first instance, inherited from the Old English, has a quite political conception, and denotes the state of a man who has no restrictions on the part of external agents. Thus, a man has freedom when he can do what he wants without anyone else telling him what to do.

All it's derivations like "free trade", "free market", "freedom of speech" or "freedom of the press", imply that nobody is going to cover your mouth, you are free to say, think, buy, sell, etc., without anyone stopping you. Even the word "free" is used for something that does not cost you, which means that nothing or nobody prevents you from taking that, or to refer to something that does not belong to anyone or any place that is not occupied by another person, like the bathroom or a parking lot.

On the contrary, the word "liberty", adopted from the Old French, has a more moralistic conception, that is, more rooted in the customs and ideas of good and evil that a people or individual has. The liberty is only possessed when man has managed to control all the internal factors that influence his actions (fear, ignorance, need, vice, etc.), therefore, he can act on his own will.

If the concept of freedom is precisely about being able to choose between all the options, without being externally blocked, the concept of liberty is about the same, but adding that you yourself cannot block the options, that is, avoid that fear, vice, impulses or your own needs control you. Therefore, a man with liberty is one who does what his moral tells him to do, because it's the right thing.

In fact, both concepts are very similar to those described by Isaiah Berlin or other authors as "negative liberty" and "positive liberty", being the first most similar to "freedom" and the second corresponding to "liberty", however, they are not exactly the same.

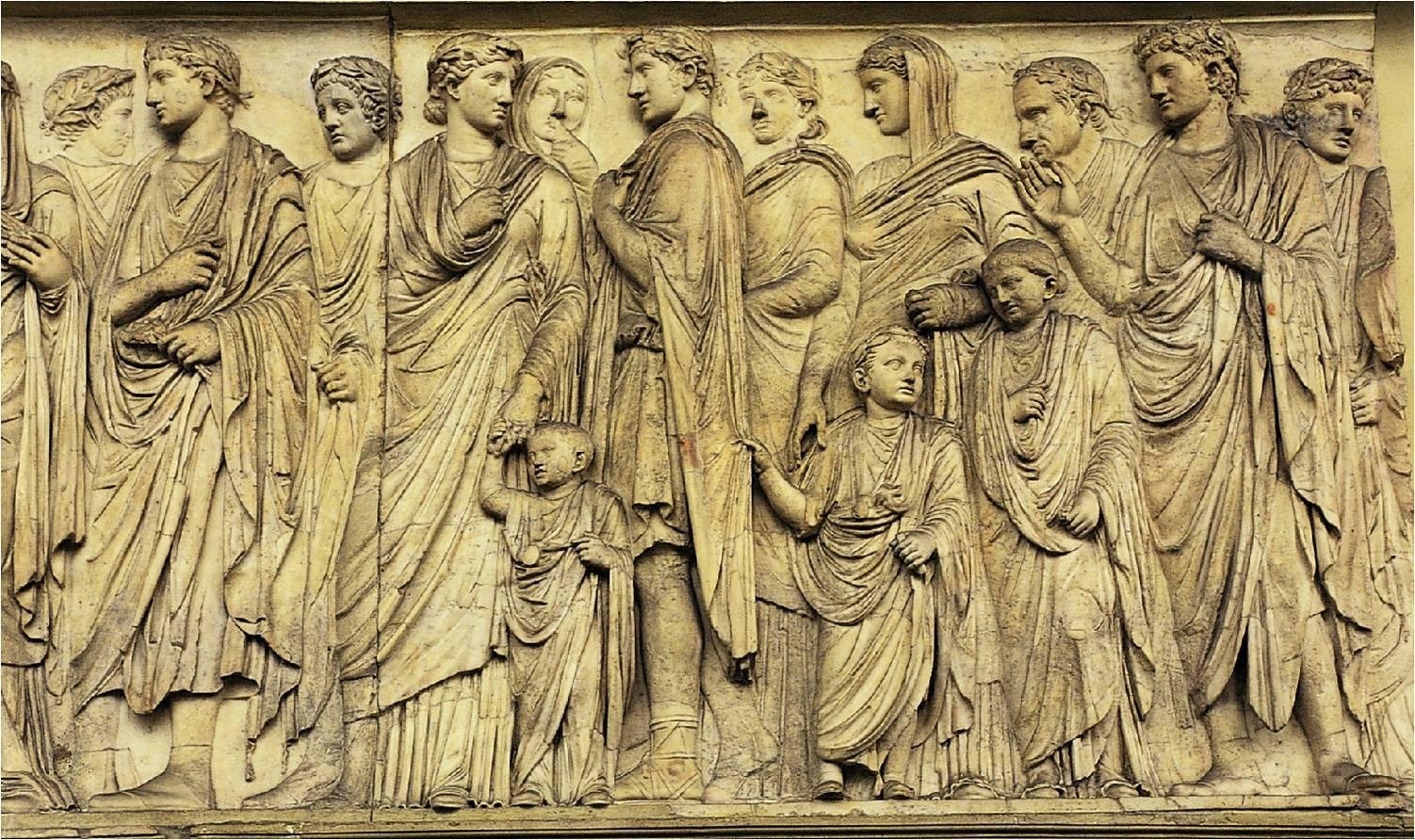

In the Indo-European world there has never been a real consensus on this word (be it liberty or freedom). The Greeks were the first to give importance to these concepts, they did not use freedom or liberty evidently, they said "eleutheria" (ἐλευθερία), and they had multiple meanings for it, although the two most important are similar to those mentioned previously. The first (similar to freedom) was a purely political conception, the Athenians had this "freedom", although it was proclaimed by any polis indiscriminately, for example, the Spartans claimed to have given freedom to all Greece after having defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War.

On the contrary, there was also a more moralistic conception of this, or more properly ethics, more similar to "liberty", which was described by many of the postsocratic philosophers of ancient Greece. Such liberty was mainly possessed by the Spartans, because they were virtuous men who did not succumb before impulses or fear, and always acted with morality, of course, a vision a little idealized, but that was the main factor that it propitiates the laconophilia existing in antiquity and that came to include philosophers as preponderant as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Xenophon, etc.

The Stoics also had a vision of the "eleutheria" based on austerity, which had nothing to do with anyone oppressing you but on the contrary had to do with self-control, and that was based on the principles of reason and virtue, in the same way that "liberty" does it.

In Rome there was talk of "lībertās", and evidently had a conception closer to the word "liberty" that derives precisely from Latin. The same happened in the Middle Ages, in fact, in the Latin world, the concept of liberty was more linked to the theological-philosophical than to the political, which only changed until the period of the Enlightenment.

During this same period, the liberal revolutionaries begin to use the word "liberty", with the meaning already mentioned above, and used with this meaning either in the Romance languages such as French, as well as in English. I have no doubt that both the Founding Fathers of America, the French revolutionaries (especially the Girondins), and even the Liberators of Latin America, who had the same influence, fought for the concept of "liberty" and not "freedom".

However, soon both words began to be used as a synonym in English, and the dominance of the Germanic nations that has been latent in the last two centuries, caused its conception to influence all the other languages, so that a semantic calque occurs, that is, a copy of the meaning of a word from another language, and the words "libertad" (Spanish), "liberdade" (Portuguese) "liberté" (French), "libertà" (Italian), as well as "liberty", become synonymous of the English freedom. I believe that this last process has increased in recent decades, where the word "liberty" has practically no meaning in itself more than that of "freedom".

And although they are now mistakenly used as synonyms, it will be important to learn this differentiation of connotations when reading ancient writings, because what we read probably does not mean only what those words mean today, and ignorance of this can lead to confusion.

Moral vs Ethics

Another confusion that I have seen that exists, although this time not only in English, is that of morals and ethics, words that are also often misused as synonyms.

The use of ethics and morality as synonyms is quite similar to that of freedom and liberty, in fact, both words have also originated in different languages (moral from Latin and ethics from Ancient Greek), however, again the connotation for both words was different, so today its meaning is also different.

The word ethics has its origin in the Ancient Greek "êthos" (ἦθος), and it was about the way of making or acquiring things, the ethics were habits, customs.

The word moral has its origin in Latin "moralis", and its meaning is also related to customs, habits.

So, why do we keep two words that apparently have the same meaning?

And the answer is, again, in the connotation that these people gave to the word. The Greeks, who were more devoted to philosophy and the study of letters, began to question the foundations of their customs. Therefore they began to wonder if what was right with respect to their customs, was really what was right at the universal level, that is, they begin to study the foundation of their habits.

On the contrary, for the Romans it is very important to act in accordance with the mos maiorum, that is, the custom of the ancestors. The Romans did not doubt the moral, don't question it, for them it is a heritage of their ancestors and it is a pride to follow it, in fact, any Roman citizen who was immoral, who did not follow the principles and genres of life assumed by the ancestors, it was considered as a shame.

Such is the love of the Romans for their morality, which is from there where the basis of their law originates, and also, a branch of it; the customary law, which are those legal rules that are not necessarily written, but that are obeyed because they are customs. The follow-up of the "mores" (principles and genres of life assumed by the ancestors), generates "consuetudines" (customs), and the follow-up of the latter generates customary laws (also consuetudinary law).

In the same way it can be seen that the study of ethics by the Greeks is a primitive form of natural law, that is, the belief that there are human rights sanctioned by nature, and that they precede written rights. The natural law is a fundamental part for the creation of universal human rights, which are rights that humans have simply for the fact of being human, and that surpass the morality of the people.

When the Romans conquered Greece, the word ethics is adopted and translated quite accurately initially as "philosophia moralis" (moral philosophy), or later, simply as "moralis" (moral), and then finally adopted in Late Latin as "ethica".

From there to the creation of the two different concepts of words that were literally similar.

It is for all this that today the word moral refers to the set of customs and norms that are considered good for directing or judging the behavior of people in a community, a very Roman conception. On the other hand, the word ethics refers to the study of good and evil, and its relations with morality, a very Greek conception.

If we are honest, for example, we are being moral, because we take an attitude that in our society is sanctioned by the customs of human behavior as good. If we study what is honesty and what is its relationship to good and evil, we would be doing ethics.

As we use both words as synonyms, a semantic calque will be produced as it has already been doing, and as it did with "liberty", so that we will lose a word as precious as ethics from our vocabulary, although I honestly don't believe that we reach those extremes.

Now, to finish, I'm going to analyze the last word I've noticed generates a lot of confusion at the time of use, and it does in all languages except one; the Spanish.

Quality

Who has not heard the classic quality-quantity dichotomy? Or the least common, though not least, dichotomy of the qualitative and quantitative.

However, although everyone can answer what is a quantity (what can be counted), and everyone can also answer what is quantitative (what is related to quantity). How many can answer what is quality?

Certainly this last question is tricky, since the word quality encompasses several meanings, from which an accurate separation could be made between two different words; the first one, is the one used when we say things like "it's good quality", and the second one, would be the one we use when we say things like "it has good qualities".

In fact, due to such differentiation, in Spanish the word "quality" is translated as two different; "calidad" and "cualidad".

The word "calidad" is used to refer to the inherent characteristics of something that allows us to judge its value. For example, when we say that a telephone is of good quality ("calidad"). This type of quality is used more in daily life, as well as in the economic sciences.

On the other hand, the word "cualidad" is used to refer to the inherent characteristics of something or someone that makes it what it is, that is, the characteristics that describe its essence. When we speak of qualitative research or qualitative analysis, we speak precisely of this type of quality ("cualidad"). This type of quality is used in philosophy and in science.

The "calidad" is therefore quantifiable, but the "cualidad" is not, although both in English are "quality", making this latter quantifiable and not quantifiable at the same time.

A few days ago I had a discussion with @eskmcdonnell where there was precisely a confusion over this word. He said that the qualities were quantifiable, on the contrary I opposed, of course, we were both talking about different definitions of quality.

It is curious that only in Spanish is there such branching of the word "quality", and in all other languages there is no. I don't know the reason for this, however, it is evident that, excluding the language barrier, the bifurcation of the word facilitates the understanding of both meanings.

As a curiosity I will mention that, both in Germanic languages as in the Romances, the origin of this word is found in the Latin "quālitās", which is in turn a calque of the Classical Greek "poiótēs" (ποιότης), which is a neologism created by Plato to refer to the inherent characteristics of something or someone that makes it what it is.

These characteristics are accessed through the questions "what", "why", "for what", "which", "who", etc., which although they don't seem to have anything to do with "quality" in English, in the Romance languages and in the Latin they are strongly related since they all start from the same root. In fact, the word "quālitās" is composed as follows:

- The interrogative: quae (what)

- The suffix: alis (relative to)

- The suffix: tat or tas (state or condition)

Therefore the word quality could be defined etymologically as; "that what is relative to the what".

Conclusion

My time at Steemit has given me the opportunity to speak with people from many countries around the globe, although everyone uses English as their usual language, the way they construct sentences and interpret the words says a lot about their perception, which is conditioned by the unconscious associations of their mother tongue.

As we learn different languages we can perceive wrong associations that bear fruit to the misuse of our language, or particular meanings given to words in our nations, but even more, people who learn other languages can open their minds to connotations of other languages, which totally changes their worldview.

But the aim of this publication was not to show what is gained by learning other languages, which never hurts, but rather what is gained by relearning our language. The only thing I did during the publication was to go to the etymological origins of the words to learn their true meaning, the one by which the words were created.

I think the vast majority of us never bother to think about how words were created in the first place. This is something that I have turned over in my head for some time, and I really don't have an answer, but if I have been able to notice something; words are only a symbolic representation of an ideal concept, if we pervert its use, and if we don't take care of knowing the ideal words and concepts that we use daily, then we will simply lose them. There is no real correlation between words (graphic signs and/or sound units) with the meaning of this (ideal concept), therefore, the only thing that unites them is our knowledge, which makes its use something more delicate than we usually think.

I see that it is impossible for us today to know how many ideas, how many meanings, and how many concepts we have lost because of the perversion of language, although we know that it is a high number, and this is inevitable, because a people can not keep very deep concepts in their dialect for a long time, and for as much as they remain written, the signs are incapable of transmitting ideas in their pure form for a long time, for this very reason Socrates left nothing written, and Plato, who did, complained that the essence of his ideas could not be conveyed in this way.

I begin to notice here a certain human curse, the one that forces our specie to know, lose, and rediscover constantly the same ideas. It is said that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, but the human is not omniscient and his memory is short, as over the years he becomes skeptical of his ancestors, and attacks his wisdom in an ignorance disguised as skepticism. And I do not criticize the skepticism per se, in fact, some days ago I made a publication supporting it to a certain extent, I criticize the skepticism that is based on our ignorance of the why of things.

At this point, I feel I could extend much more and duplicate what I have done so far, but it would be in vain, I think my points have been more than clear. So I say goodbye, hoping that the hieroglyphs I've made can convey what I think.