Let’s first start from what the term diagnosis actually means:

Diagnosis is the stage through which a clinician examines signs (e.g. crying) and symptoms (e.g. feelings of sadness) of a person in order to find out whether they characterize a disabling, endangering disorder. It is an essential process in the field of mental health as it plays a fundamental role in the decision of what treatment to go for. In a perfect world taking into account the interplay between psychological, social and biological factors as well as the influence they exert on the individual would be paramount in determining mental illnesses.

When did it all begin?

In ancient Greece, as you might have guessed. Well, the term diagnosis itself comes from the Greek diagignoskein which means: to recognize, to distinguish. So, around 400 BC Hippocrates proposed the Humoral Theory that explained and diagnosed mental disorders according to the imbalance existent among the four types of humours that every person possesses. These were meant to be the substances that filled the cavities of the human body and when out of balance would give rise to phobias, melancholy or hysteria; illnesses which were already described and diagnosed back then. This diagnostic system was respected by Muslim, Roman as well as European doctors up to mid-18th century.

From the 18th century onwards

That was a time when the emergence of the microscope contributed to a more biological frame of reference. Here the humoral theory gave way to the scrutiny and dissection of organs and tissues. The study of illnesses then was done through a new lens that focused on the biochemical and biological workings of body parts and invisible germs. The biomedical model was born, changing the way mental health was viewed in Western Countries, initiating a mission to differentiate what is ‘normal’ and ‘ill’ while also deciding where to draw the line between both states.

It was within this new climate in the medical field that German psychiatrist Emil Kraepeling put forward the idea that physical and mental disorders should be classified in the same way. In other words, arrange them in groups and subgroups. He then, for the first time, proceeded with differentiating between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Kraepelin’s classification system is regarded as a scientific legacy because it made possible for clinicians to foresee the course and outcome of certain mental illnesses. For example, as when he suggested that bipolar disorder (then, known as manic-depressive psychosis) was a disturbance of the individual’s mood resulted from metabolic imperfections.

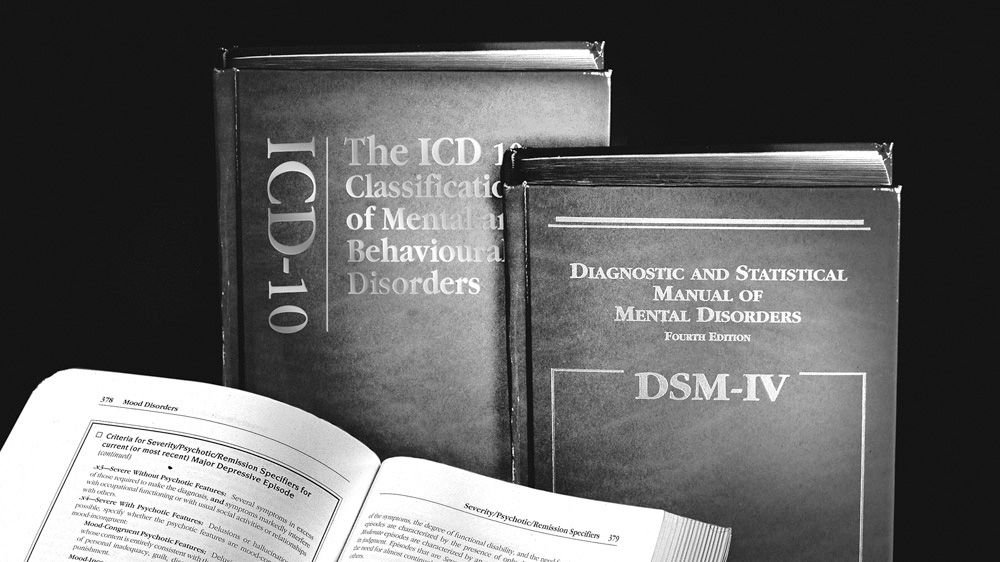

Of course, Kraepeling did not get it all right. However, his classification methods delivered the underlying concept for the modern system of diagnosis of mental health which is currently applied by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders(DSM) and the International Statistical Classifications of Diseases and Related Health Problems(ICD).

Diagnosing Mental Illness in the 20th century: the DSM & ICD

There are currently two classification systems for mental illnesses: the ICD, published by the World Health Organization and the DSM, published by the American Psychiatric Association. It is worth highlighting here that while the ICD includes other kinds of health problems the DSM addresses solely mental disorders. Despite a few discrepancies both the APA and WHO work together to use the same codes and strive for consistency in order to make the diagnosis process of mental illnesses objective, systematic and exhaustive.

Worldwide, out of the two, the ICD is the preferred one for clinical diagnosis. But, in the USA and the UK the DSM is the classification system most adopted by mental health professionals. The DSM was first published by the APA in 1952. It is currently in its fifth edition and its revisions are based on analyses of data, field trials and reviews of pieces of research.

As new revisions take place an increasing trend in diagnostic categories is seen. For example, the DSM’s first edition included 106 categories while its current edition includes 297. This is because of new acquired understanding of disorders and the influence of social norms. The category corresponding to autism was only included in the 1980’s revision. Naturally, there are also those categories which are eliminated due to the lack of evidence to support them. ‘Substance abuse’ is one of them, as clinicians faced problems in efficiently differentiating it from ‘substance dependence’.

The Rosenhan’s experiment

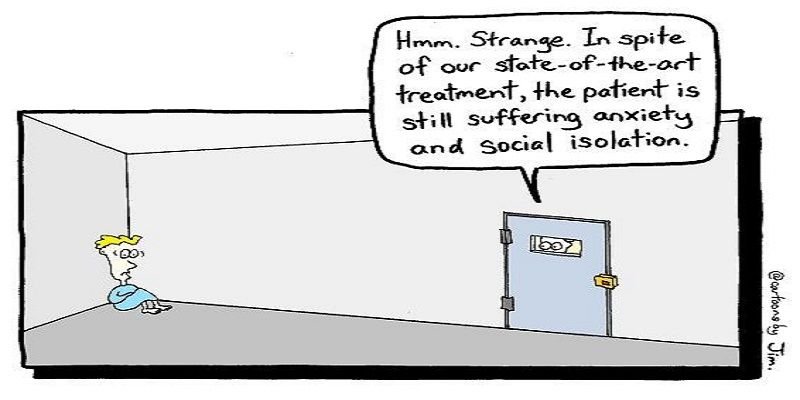

Still, having a diagnostic system in hand doesn’t necessarily mean that clinicians always arrive to the correct diagnosis, and this is a reality the psychologist David Rosenhan exposed in 1973.

In his (now) classic study Rosenhan and another seven pseudo-patients, during interviews in mental hospitals in the USA, claimed to have been hearing voices, but also spoke of all the health aspects of their daily life and stated that they had never been afflicted by any mental disorder before. It turns out that all, except one, pseudo-patient were diagnosed with schizophrenia in 12 different hospitals. It took them an average of 19 days to be discharged, with some of them staying in the mental hospital for as long as 52 days. Many other in-patients actually detected their ‘normality’ while the hospital staff, although consistently stating that the pseudo-patients were friendly still believed they were mentally ill upon discharge as they were let go under the observation ‘schizophrenia in remission’.

This, of course, did not go well within the psychiatric setting. So, what did Rosenhan do? A follow-up! The follow-up experiment, however, exposed yet something else the ways that expectations might influence the outcome of diagnosis. The assumption of having pseudo-patients among their genuine ones caused hospital staff to identify 41 out of 193 such patients, when in reality in the second experiment there was none.

Although it is worth highlighting that since the 70’s the DSM’s diagnostic categories has improved its reliability. More recent evidence put in question once again the diagnosis of mental illnesses. Repeating Rosenhan’s study, psychologist Lauren Slauter herself went to various hospitals across California. Despite not having been admitted to any hospital she was diagnosed with various conditions, including PTSD, psychosis and depression.

Is diagnosis a label?

Thomas Szasz suggests that the entire system of diagnosis should be discarded. His argument is that labeling someone with a mental illness is inherently biased. Furthermore, he argues that diagnosis is about rejecting behaviors and perspectives that do not ‘fit’ in the norms of society. Nevertheless, while to some the diagnosis of a mental health condition may come with a label subjected to stigmatization; to others it may bring understanding and relief.

How? Well, take the example of a mother who has overwhelming intrusive thoughts about hurting her children. She knows she loves her children but keeps having these frightening thoughts coming back. In order to free herself from these uninvited ideas she rocks back and forth, over and over again. When she realizes what she is doing she thinks she has lost her sanity. The moment this mother is diagnosed with OCD she has a huge weight lifted from her shoulders, she is reassured that she is a good mother and she is convinced of the love she has for her children. She understands that it is not ‘her’, but rather her condition.

A correct diagnosis does not have to be a label. However, this is a reality that first and foremost must be accepted by the actual individual who has received one. Although mental disorders still, unfortunately, carry a stigma; individuals with major depression, OCD or psychosis among other conditions should not been pigeon-holed. They should rather be regarded as people with particular problems that they need help with. Problems that might have resulted from biological, psychological or social factors; or, indeed, from the interplay between them. After all, who does not have problems?

Summary

• Diagnosis is the identification of signs and symptoms of a disorder that might disable and/or endanger an individual.

• The diagnosis of mental illnesses started way back in 400 BC Greece.

• Humoral Theory described and differentiated mental disorders according to the imbalance of humours, 4 different substances that filled the body cavities.

• Kraepelin’s new classification methods made possible for clinicians to foresee the course and outcome of mental illnesses.

• The current diagnosis of mental illness follows the codes and classification system of the DSM and the ICD.

• Rosenhan’s experiment exposed both the ways mental health care professionals arrived to a diagnosis and the role of expectation in the process.

• At the same time a diagnosis can be, for some, a label that comes with stigmatization; for others, it provides understanding and relief.

[Original Content by Abigail Dantes 2017]

It means the world to me 😊

Reference List:

APA (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn.

Pincus, H.A., Frances, A., Davis, W.W., First, M.B. and Widiger, T.A. (1992) ‘DSM-IV and new diagnostic categories: holding the line on proliferation’, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, vol. 60, pp. 646-7.

Rosenhan, D.L (1973) ‘On being sane in insane places’, Science, vol. 179, no. 407, pp. 250-8.

Szasz, T. (1994) Cruel compassion: Psychiatry’s control of society’s unwanted, New York, Wiley.