You're at a summer camp and have made some friends on your first day. You get along with three people particularly well: they are nice, friendly, and one you find very attractive.

On the second day you need to form a team to build a raft. You choose the three you like the most rationalising that since they are nice, they must be good at raft building.

Congratulations! You've just fallen victim to the halo effect!

Soldier evaluations

The halo effect is one of the oldest cognitive biases. The term was coined in a research paper by Edward Thorndike almost one hundred years ago in 1920.

In an experiment he asked two commanding officers to evaluate their soldiers over a range of qualities such as physique, intellect, leadership, loyalty and cooperation.

He discovered that there was too high a correlation in the responses. For example, if a soldier was rated high in terms of physique, the soldier would also be rated high in terms of intellect, leadership and character. On the other hand, if a soldier was rated negatively in one characteristic, this would also correlate with the soldier's other results.

Marketing

The halo effect is used very often in marketing to try to associate a new product with something or someone that has a positive image in the hope to attract more customers.

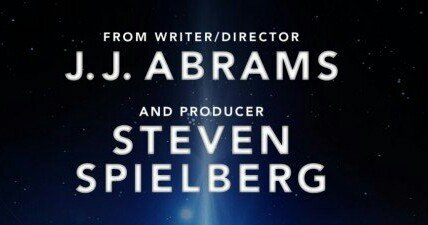

In most film posters, for example, the producers are accredited in small text at the bottom; that is, unless you're Steven Spielberg.

Due to his celebrity and fame in film making, anything he touches warrants his name being up front and center because, due to the halo effect, it becomes more attractive.

Similarly, films that star Oscar winning actors and directors add this to the trailer and advertising, hoping you'll associate their previous and unrelated success with the new movie. In fact, they don't even need to win. Being nominated is enough to allow the marketing team to associate the movie with the prestigious award ceremony.

What can we do about it?

When performing an evaluation, whether it's for a product or a person, try to look past general feelings about what you're evaluating. It can help to consider beforehand what traits are important and concentrate on those during the evaluation.

When being evaluated you can take advantage of the halo effect by first talking about something you are good at and follow with a different trait you'd like to induce the interviewer into thinking you're equally good at.

Banner photo by Gordon Wrigley used under the CC-BY-2.0 license. Changes were made to the original.

Other posts in the series:

- The lies we tell ourselves - the gambler's fallacy

- The lies we tell ourselves - the sunk cost fallacy

- The lies we tell ourselves - the framing effect

- The lies we tell ourselves - cognitive dissonance

- The lies we tell ourselves - confirmation bias

If you liked this post, or any others I've written, don't forget to follow me.