THE PSYCHOLOGY OF ANARCHISTS AND ANARCHISM

(Slightly adapted from the transcript of a speech given by

Dr Aiden P Gregg at the first annual Anarchapulco conference, February 2015)

Hello! My name is Dr Aiden P. Gregg. I’m an associate professor of psychology at the University of Southampton, UK, with a PhD from Yale. I’m also an anarchist. Hence, the inevitable topic of my talk: the psychology of anarchy. (And pay attention class: there will be quiz after the break!)

A Cautionary Note on Psychological Explanations

So, we’re all a bunch of anarchists here. The question naturally arises: how did we get to be so crazy? Now, maybe we don’t think we’re crazy; but most other people do. And they’d like to know why. But of course, we know that we’re the sane ones: it’s those statists who are crazy. And we’d like to know why. So, is just one of us crazy? Or both? Or neither?

Let’s go into this a bit. To say someone is, loosely speaking, crazy, is dismiss their beliefs as irrational, to assume that that someone lacks adequate grounds for holding them. Instead, their beliefs have some sort of causal explanation, involving defective mental operations. To be sure, some people are, ideologically speaking, either crazy or sane: there is some objective truth to the matter. Even so, we have to cautious about attributing craziness.

First, ideological opponents naturally tend to deride and caricature one another: they generally consider their opponents to be crazier than themselves. For example, in research I am conducting into intellectual arrogance, I recently asked respondents to rate people, who believed the opposite of what they did, on 24 hot-button political topics, in terms of how much, relative to the average, their opponents were: good versus evil, smart versus dumb, unbiased versus biased. Guess what? They duly rated them as more evil, dumb, and biased, than average. And this is just what people admit: it may be worse in reality! Empirical research in political psychology finds something similar: both left-wingers and right-wingers think their opponents are more extreme than they actually are (Robinson, Keltner, Ward, & Ross, 1995).

Moreover, even empirical researchers in social and personality psychology—who happen to be overwhelmingly left-wing—have recently been accused of pursuing hidden research agendas designed to disparage the right-wing (Duarte et al., 2015). Finally, for those who can remember the Cold War, it was standard for the USSR to deem dissidents schizophrenic. So, we should be on our guard about explaining our opponents’ viewpoints in terms of psychology, because psychology tells us that we have a bias towards doing so!

Second, it is arguable that psychology can never fully explain why people believe what they do. Suppose I believe, correctly, that Jeff Berwick is cool. Do I believe Jeff is cool because I have grounds for believing Jeff is cool, or because my psychology makes me believe it? If my psychology makes me believe it, then the fact that Jeff really is cool is beside the point. But it’s only crazy people whose psychology makes them believe stuff: sane people base their beliefs on criteria. So the most we can say is that psychological factors, of one sort or another, incline sane people, but do not compel them, to hold beliefs. For example, suppose that I am particularly wilful, preferring to do my own thing. If so, I might be inclined towards anarchism. I might grasp it more intuitively, or give it the ideology the benefit of the doubt. But that would not compel me to endorse it, and nor indeed would any other psychological factor. If I was rational, I would still need grounds for believing anarchism was true. Sane people don’t just believe whatever the hell suits them.

Third, explaining political beliefs psychologically is a little bit like explaining sexual orientation psychologically. From a biased “heteronormative” point of view, it is being gay—as a deviation from the norm of straightness—that requires explanation. But no less worthy of explanation is why the norm of straightness itself exists. Why do most people prefer partners with non-matching naughty bits, and only a few people prefer partners with matching naughty bits? A complete explanation of sexual orientation must encompass both the norm and deviations. The same goes for psychological accounts of political orientation: inclinations towards both anarchism and statism should considered alongside one another as equal partners. Here, for example, you might cite being more wilful or compliant as psychological factors predisposing people to anarchism or statism respectively.

Ultimately, my point of this: we don’t want to get into the business of using psychological explanations as ad hominems against those with whom we happen to disagree. Let’s assume the possibility that all of us are, at least, somewhat rational, and that psychology only explains our partial irrationality.

The Psychology of Anarchists (versus Statists)

So with these preliminary caveats out of the way, what can we say about the psychology of anarchism (versus statism)?

The answer is, so far, only a modest amount. The topic is not well developed. Indeed, as such, it doesn’t yet exist: there is no body of empirical research yet addressing it explicitly. Perhaps there simply haven’t been enough anarchists around to bother studying them, even as a rare clinical aberration. Instead, most research in political psychology explores the causes, correlates, and consequences of variations along the single bipolar dimension of left-versus-right. Variations across the orthogonal bipolar dimension of anarchism-versus-statism—often differently labelled, for example as individualism-versus-collectivism—has been barely studied. Anarchists, of course, would pile up on the extreme end of this dimension, whatever their left-right preferences. Still, we can address the psychology of anarchism (versus statism) in a preliminary way, drawing on a mixture of pertinent findings, and engaging in some plausible speculations.

One place to start is with the ugly sister of anarchism, namely, libertarianism—forever trying to fit the fat foot of government into the crystal slipper of freedom. Mainstream political psychology has recently decided that libertarians, having reached a critical mass, can no longer be ignored. Now, given that anarchists are closer to libertarians than to anyone other political group, the findings might conceivably generalize. (I should also mention in passing, without elaborating further here, that the libertarian movement contributed to psychology in the late 20th Century, though the work of Ayn Rand and Nathaniel Branden on the nature of self-esteem Rand (1964), Thomas Szasz on the myth of mental illness Szasz (1961), and Albert Ellis on the practice of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (Ellis, 2004).

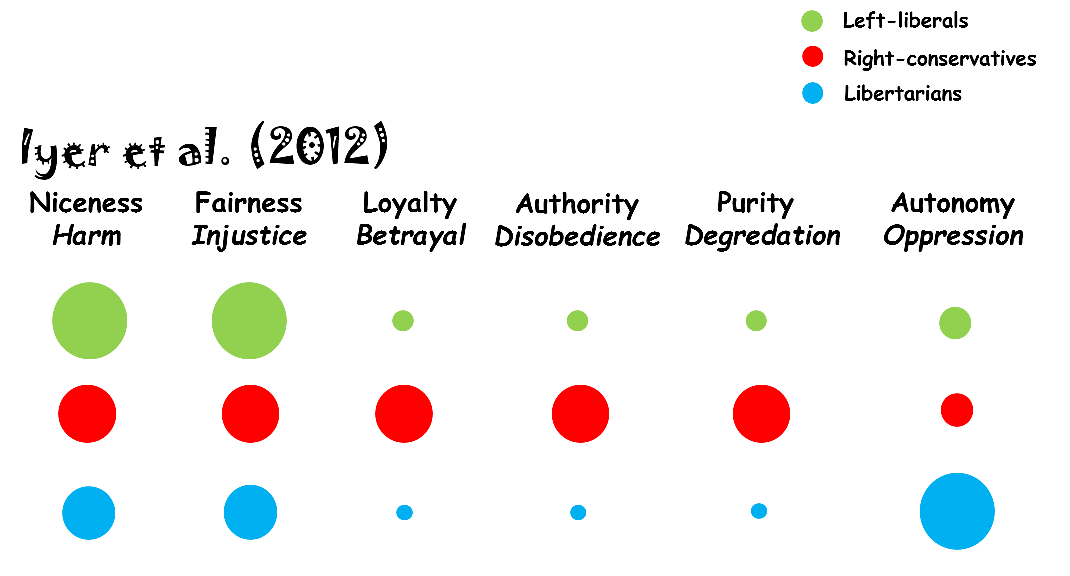

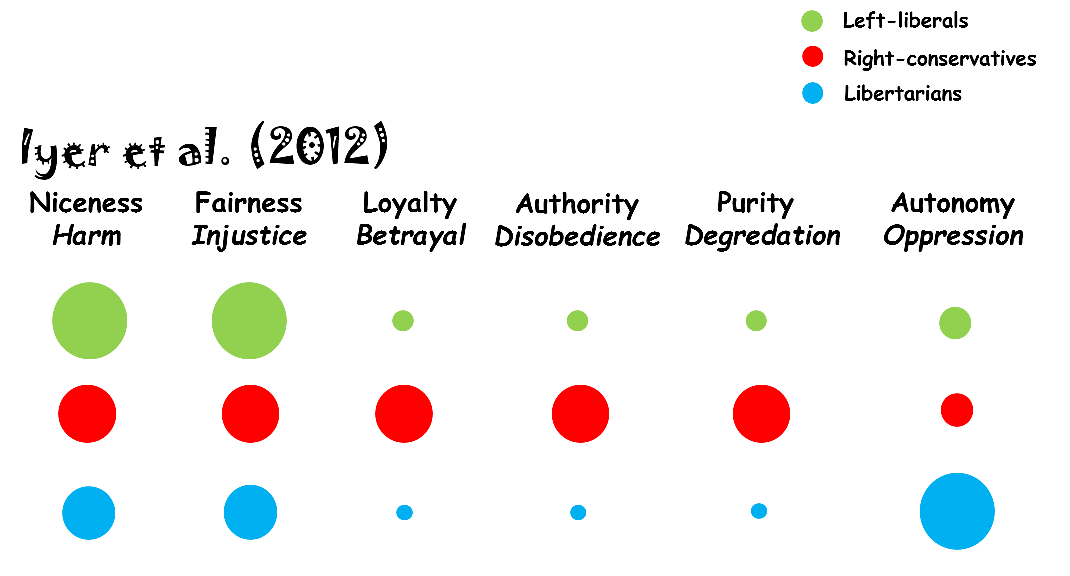

So let’s jump into a recent large questionnaire study conducted by Iyer and colleagues in 2012 (Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto & Haidt, 2012). Its purpose was to compare and contrast self-identified libertarians against self-identified liberals and conservatives (i.e., left-wingers and right-wingers) in several key respects. To do so, the researchers drew, among other things, on the work of noted psychologist Jonathan Haidt, the pioneer of moral foundations theory. The idea here is that the bases of morality are many, somewhat akin to distinct taste receptors on the tongue; and although these moral bases are not irresistible, they are powerfully intuitive, such that people struggle to articulate rational justifications for them. Here are the six moral bases: being nice; playing fair; staying loyal; obeying authority; maintaining purity; and pursuing autonomy. Otherwise conceived, they serve as intuitions against: harm, cheating, betrayal, disobedience, degradation, and oppression. For starters, one can distinguish liberals from conservatives in terms of how much different bases matter to them. To liberals, the first two (no harm, no cheating) matter more than the next three (no betrayal, no subordination, no degradation); to conservatives, however, all five matter about the same (Haidt, 2012). This suggests that left-wingers may be deficient in some moral bases, explaining why they don’t “get” conservatism. As for libertarians, they value the sixth moral base (no oppression) more than all the other, and more than liberals and conservatives do. Apart from that, they show a profile pattern like that of liberals.

Responses to other questionnaire paint a picture of libertarians—who incidentally emerge as a coherent cluster of people in their own right—as cleverer but colder. They are systematizing rationalists rather than empathizing sentimentalists, who are inclined identify more with non-moral more than with moral traits—a characteristic that they share, somewhat worryingly, with people scoring high in psychopathy. Not surprisingly, most libertarians are also male. However, in considering all of this, recall that the links here are tendencies, not certainties, and the underlying causality remains speculative. Even if calculating curmudgeons are statistically more inclined to libertarianism, this does not mean that libertarianism is a philosophy all about, or only designed for, calculating curmudgeons.

Can we generalize these findings to anarchists, or indeed at all? One limitation of the Iyer study is that it was US-based, so it findings may be peculiar to US politics. Another limitation is that respondents labelled their own political affiliation, and we know that such labels map only loosely onto formal policy positions. Moreover, the simple left-right continuum used in the study misses much about people’s politics, in particular, by conflating their social and economic views. For example, social conservatives tend to be somewhat more economically laissez-faire. For their part, libertarians and anarchists tend to be very economically laissez-faire, and somewhat more socially liberal. But it varies. Freedom-lovers often differ significantly over abortion, for example.

But suppose these limitations are not fatal. One might then reasonably hypothesize that anarchists are extreme libertarians—the full-fat, no-artificial-government-added, version. If so, they should be like libertarians, only more so. In support of this, many anarchists have made the journey to anarchism gradually, as Jeff Berwick has documented on his Anarchast webcast, suggesting a continuum. But the difference between libertarians and anarchism might still be qualitative as well as quantitative. To reject government in all its forms is a fundamental step, and may be psychologically distinctive. In terms of the moral bases, I would surmise that anarchists would be exceptionally blasé about disobedience but exceptionally exercised about oppression. I would also surmise that anarchocapitalists, in particular, may be more prosocial, rather than more antisocial, than your average libertarian, because they are exceptionally clued in to how free exchanges conduce to the social good, and are striving actively to construct bottom-up alternatives to the top-down institutions of the state—peaceful parenting and blockchain initiatives being a case in point. Anarchocommunists, however, we can expect to be really grumpy and smash things.

That people gradually become anarchists, however, does not mean that all anarchists are made rather than born. Perhaps only some people can, as Doug Casey (2013) has suggested, ever become anarchists, as only they have the right genes. However, it’s more likely that people merely differ in their preparedness to become anarchists. We should also note that political arrangements such as democracy, once unknown, have now spread near-universally, to the extent that people have trouble envisaging viable alternatives. This implies that political beliefs are historically malleable. Yesterday, monarchy; today, democracy; tomorrow, anarchy.

It’s also significant, I suggest, that libertarians, and perhaps anarchists too, seem to endorse the autonomy base of morality over all the others. My interpretation here is that they prioritize ethics over morality. But this, I mean that, being more systematic in their thinking—and anarchists are hyper-systematic in endorsing the Non-Aggression Principle—they tend to have a rationally worked out philosophy governing how adult humans should productively interact, one that transcends and overrides more primitive intuitions, and which may not even itself even be strongly based in intuition. In Randian terms, it’s all about objective reason, not subjective whims. It is also possible that, being a little dispositionally hard-hearted, as well as somewhat cognitively superior, gives anarchists and libertarians the ability to ignore moral intuitions in the short-term, so as to satisfy them in the long-term. For example, the socialist redistribution of wealth satisfies the moral intuition of avoiding harm today, but defies it tomorrow when it prompts economic miscalculation that makes people poorer. In contrast, the capitalistic accumulation of wealth defies that intuition today, but satisfies it tomorrow when it prompts enhanced productivity that makes people richer. Anarchists and libertarians may be better able to entertain without dismay the idea of not alleviating harm today in order to alleviate more of it tomorrow.

A final point to make is that the psychological profile of anarchists may be related, not only to the fact that they endorse anarchism, but also to the fact that anarchism is still—even if decreasingly so—a minority political orientation. If you are rather conventional in outlook, or lack the courage of your convictions, then you can’t really become an anarchist. Accordingly, anarchists should be both kookier and brasher than average. For example, you should tend to find them on internet forums, arguing September 11th was an inside job using only capital letters. Note, however, that such kooky brashness might also have characterized, for example, the early defenders of democracy in the era of monarchy, or emancipation in the age of slavery. Note also that, although kooky brashness can signal maladjustment—in particular, schizoid or paranoid personality disorder—its logical contrary, meek complacency, can signal hyperadjustment—in particular, underdiagnosed ovinoid personality disorder—more commonly known as “Sheeple Syndrome”.

The Psychology of Anarchism (versus Statism)

I would like to move on from the psychology of anarchists (versus statists) to the psychology of anarchism (versus statism). Relevant empirical research, from which plausible extrapolations can be drawn, suggests that adoption of the anarchism as a political philosophy is likely to face a number of characteristic psychological barriers.

One barrier that is not psychological—but is relevant by way of alternative or baseline explanation—is sheer exposure to the idea of anarchism. Until encountered, the idea of anarchism can be neither accepted nor rejected, either rationally or irrationally. Arguably, the internet, and rise of alternative media, has been instrumental in spreading anarchistic ideas—with Ron Paul as perhaps a gateway drug. So much of the battle is getting the word out, rather than converting the obstinate. In my own case, I never heard of anarchistic ideas until a few years ago. Once I did, they struck me as well worth considering, and after much reflection, I endorsed them, and possibly because I am little kooky.

What defines anarchism, of course, is the rejection of the legitimacy of government. The case against the state’s right to coerce, and our duty to obey it, has often been made, most recently with rhetorical passion by Larken Rose (2011), and with philosophical rigor by Michael Huemer (2013). And indeed, it’s seems hard to defend why, just because some selected group of special people, the government, declare that I must do something, especially where that something is bad or harms me, that I must do it, when all other groups lack that privilege. Equally, it’s prima facie puzzling why most people habitually accept that they must submit to such declarations. Seemingly, people can’t easily escape the idea or influence of authority.

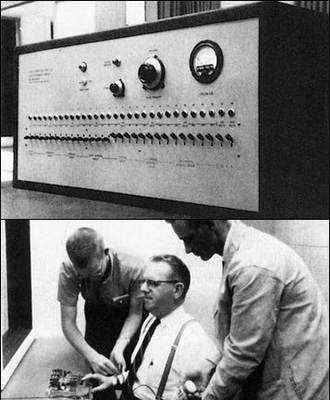

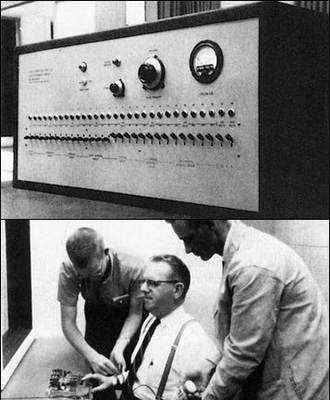

Classic studies from the field of social psychology bear this out. For example, Stanley Milgram notoriously demonstrated that two-thirds of ordinary people will obey to the bitter end an experimenter in a lab coat who instructs them to escalate harm against an innocent person—a poor learner with a heart condition, who screams in pain at the increasingly intense electric shocks he is being administered by way of punishment, before ominously going silent (Milgram, 1963).

But at least these subjects here were unwilling perpetrators: they accepted the authority figure as legitimate, because they obeyed, but not the order itself. Yet other lines of more contemporary research—from social psychologists such as John Jost, Aaron Kay, Scott Eidelman and Chris Crandall—suggest that people will also default to accepting existing states of affairs as legitimate, including political arrangements that entail status differences (Eidelmann & Crandall, 2012; Jost, Banaji, & Nosek, 2004; Van der Toorn et al., 2015). In effect, and defying the philosopher David Hume, people derive an “ought” from an “is”. They are either (a) motivated to uphold the status quo, as a way to reassure themselves, or (b) are cognitively inclined to uphold the status quo, as a simple rule-of-thumb.

Let’s start with the motivation. The prospect that reality is evil or inhospitable—whether it is one’s own reality, or that of another—is troubling. People therefore want to believe in a just and propitious world (Lerner, 1980). When injustice and misfortune strike, as they must, they then have two options: either abandon that cherished belief, or engage in defensive rationalization. People often resolve the painful cognitive dissonance by doing the latter. One dramatic example—so-called “Stockholm syndrome”—occurs when a victim who cannot escape a kidnapper defensively identifies with them. By extension, those who cannot escape the burden of taxation, where an omnipotent state effect inexorably seizes their stuff, should defensively identify with the state, whatever the merits of arguments for or against taxation. Research also shows that people tend to blame innocent victims for their own misfortune, as means of parrying the threat to a benign view of the world. Accordingly, people should be inclined to condemn convicted tax evaders, whose plight would otherwise imply they are victims of indefensible abuse.

Pertinent here is something called system justification theory (Jost et al., 2004). Its goal is to explain why those who suffer as a result of some social system should nonetheless paradoxically endorse that system—for example, why women in Saudi Arabia, and not only men, often regard women as unfit to drive (Abdel-Raheem, 2013). Betraying its Marxists roots, however, system justification theory tendentiously assumes that the enemy is social hierarchy in general rather than political aggression in particular. It assumes, for example, that the any tendency to endorse capitalism, meritocracy, or a Protestant work ethic is inherently ideological in nature, serving only to rationalize an unjust social order (Jost & Hunyady, 2005). Ultimately, the non-endorsement of a leftist worldview, devoted to redressing inequalities allegedly stemming from external oppression, is regarded by the theory as a species of “false consciousness”. However, anarchocapitalists—who can appreciate that at least some material inequality is legitimate given that it reflects natural variations in internal factors such as effort and talent—would put forward an alternative hypothesis. The real “false consciousness” involves regarding the disparity in power between the individual and state as legitimate, whether that state is left-wing, and coercing people into funding welfare, or right-wing, and coercing people into funding warfare. Arguably, government itself is a more general s system than any particular type of government, so its evils should be more generally rationalized.

But sheer cognition alone also validates the status quo. Suppose you have people choose between two reasonable options, A and B. In key studies, these have been investment opportunities, universities policies, possible electoral candidates, or imagined election outcomes (Eidelman & Crandall, 2014; Samuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988). Some people are told that A is the current arrangement and B the possible alternative, and some are told the opposite. With the options counterbalanced, people overall prefer the current arrangement (especially if they do not think about it; superficial thought generally results in politically conservative judgments).

Note that, although this preference is irrational here, it’s not necessarily irrational in general. By and large, current arrangements have proved themselves to be at least tolerable, and alternative arrangements would have to be significantly and predictably better, just to offset the costs and risks of transition. Such considerations inspire the Burkean political philosophy: that we should be careful about replacing current political arrangements, because, however bad they are, the alternatives are likely to be even worse, because familiarity dulls appreciation of existing benefits, and revolutionaries overestimate the likelihood of alternative utopias (Sowell, 2002). Moreover, bad prospects psychologically outweigh good prospects. For example, the loss of one bitcoin—for MtGox or wherever—is more disappointing than the gain of one bitcoin is cheering. Such loss aversion (Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1991) makes evolutionary sense: losing is typically more fatal for survival than not winning. That said, sometimes the alternative really is better. So if anarchism really is better, then status quo bias will psychologically incline people to oppose it.

There is also a sense in which the status quo can be a matter of degree. While mere existence makes people value things more—people prefer, for example, galaxies whose shape is said to be the majority of those in existence—if some state of affairs has existed for a long time, or are difficult to avoid, so they are really part of reality, then people tend to evaluate it more positively still (Eidelman & Crandall, 2014). For example, studies show that people think acupuncture and capitalism are both more legitimate if they have been portrayed as having deep historical roots. People also prefer the actual taste of drinks described falsely as being well-established brands. Moreover, if people are told it is harder to leave their country, they tend to be more in favour of its current political arrangements. And if people are led to believe that they depend upon some authority, they then tend to regard that authority as more legitimate, to defer to it more, and regard the outcomes it brings about as more positive. Given that the state has been around a while, and is unlikely to be replaced soon—meaning that it is very much the status quo—its merits are liable to be overestimated, whatever they happen to be.

Another cognitive explanation for resistance to anarchocapitalism is that elements of the case for it are complex and counterintuitive. Fully grasping the case for them takes time and effort, if not careful study. In this respect, anarchocapitalism resembles probability theory, which although provably sound, yields surprising results. For example, how many people need to be in a group for two of them to have a 50% chance, or a 99% chance, of sharing the same birthday? The answers are 23 and 60, respectively; mathematics proves it, but the figures seem impossibly low. Similarly, coercing employers into paying a minimum wage to poorly skilled employees would seem intuitively to improve their welfare, by obliging profit-seeking employers to pay them more than they otherwise might. However, careful analysis provides excellent, if more subtle reasons, to doubt whether this intended effect would transpire. Specifically, whereas competition between employers in a free market would naturally tend to ensure that employees got paid based on their productivity—because employers would attempt to selfishly outbid each other for employees’ labour until it became unprofitable to do so—forcing employers to pay prospective employees a minimum wage would counterproductively disincentivize them from hiring low skilled employees in the first place, because such employees would now reduce rather than increase profits. That’s a bit complicated. It’s far easier just to assume that the economic effect of a policy will correspond its political intent.

But I suspect the greatest cognitive obstacle to the acceptance of anarchism is that failure to appreciate the actual and potential role of spontaneous order in human affairs. The commonplace fear is that, without someone in charge, however incompetent or corrupt, anarchy would precipitate chaos. With no Leviathan around, the economy would fall apart, and scoundrels would run riot. Here, people arguably over-extrapolate from their interpersonal experiences on a small scale to how society must operate on a large scale. In small businesses, where people all know one another, plans are based on local knowledge, and decision-making is hierarchical. Someone is in charge and runs things. However, this model does not scale up. As Hayek (1945) and others have shown, knowledge is dispersed on society, so the only way that goods and services can be directed to their most urgent uses, now and in the future, is to permit the price system to freely reflect dynamic fluctuations in supply and demand, permitting innumerable specialists, who could not otherwise know what to do, to collaborate productively to the benefit of everyone. As regards law and order, clearly the scoundrels must be deterred. However, there is every indication that distributed defence is liable to be at least as effective as centralized defence. If rules make sense, and the majority are decent, then the majority will abide by them out of self-interest, and will not need a ruler to intimate them into doing so. Furthermore, rulers are liable to take advantage of their position; and without rulers who are obeyed, large-scale war would be difficult, as most people quickly weary of death, destruction, and poor wifi access.

So, suppose we find ourselves, as evangelical anarchists, encountering in those to whom we make our case, not only rational reserve, but also irrational resistance. What practical recommendations does psychology have to offer? Many could be made, but I just select two.

First, frame pro-anarchy arguments in ways that harmonize with people’s moral intuitions, rather than in ways that conflict with them, or that fail to engage them. For example, with left-wingers, appeal to their intuitions about preventing harm or injustice. Is not the Non-Aggression Principle a prescription for peace, love, and harmony? Is it not entirely fair that entrepreneurs who take risks, exhibit foresight, and work hard, should reap the associated benefits? Similarly, with right-wingers appeal to their moral intuitions about preventing disobedience, betrayal, and degradation. Is not the Non-Aggression Principle a worthy law to respect and submit to? Is not honouring private contracts a manifestation of interpersonal loyalty? Isn’t refusing to violate people’s property indicative of moral purity, just like refusing to violate their person?

Second, emphasize the contingency of the state. To the extent that the state is seen as a political arrangement that just happens to be in force here and now, rather than in all times and all places—and to the extent that it seen as subject to decline rather than hardwired into the essence of human society—people will be less inclined to judge it positively and to rationalize its activities. Seeing the state in context—as one way things can be, rather than the only way it must be—is aided by travel, which underlines its geographical contingency, and by reading, which underlines its historical contingency.

References

Abdel-Raheem, A. (2013, November 2). Word to the west: Many Saudi women oppose lifting the driving ban. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/

Casey, D. [CapitalismMorality]. (2013, January 9). Doug Casey - Socialism and Psychological Aberration (Capitalism & Morality Seminar 2012) [Video file]. Retrieved from [http]:

Duarte, J. L., Crawford, J. T., Stern, C., Haidt, J., Jussim, L., & Tetlock, P. E. (2015). Political diversity will improve social psychological science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, 1-13.DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X14000430

Eidelmann, S., & Crandall, C. C. (2012). Bias in favor of the status quo. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6, 270–281.

Eidelman, S., & Crandall, C. S. (2014). The intuitive traditionalist: How biases for existence and longevity promote the status quo. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 50, 53-104.

Ellis, A. (2004). Rational emotive behavior therapy: It works for me—it can work for you. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Haidt, J. (2012). The righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. New York: Pantheon.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. American Economic Review, 35, 519–530.

Huemer, M. (2013). The problem of political authority: An examination of the right to coerce and the duty to obey. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Iyer, R., Koleva, S., Graham, J., Ditto P., & Haidt, J. (2012). Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological dispositions of self-identified libertarians. PLoS ONE, 7(8): e42366. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042366

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of System Justification Theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. International Society of Political Psychology, 25, 881–919. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00402.x

Jost, J. T., & Hunyady, O. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of system-justifying ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 260-265.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5, 193–206. doi:10.1257/jep.5.1.193

Lerner, M. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. Plenum: New York.

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 371–378. doi:10.1037/h0040525

Rand, A. (1964). The virtue of selfishness: A new concept of egoism. New York: New American Library.

Rose, L. (2011). The most dangerous superstition. Self-published.

Robinson, R., Keltner, D., Ward, A., & Ross, L. (1995). Actual versus assumed differences in construal: "Naive realism" in intergroup perception and conflict. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 404-417. DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.3.404

Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1, 7–59. doi:10.1007/bf00055564

Sowell, T. (2002). A conflict of visions: The ideological origins of political struggles. New York: Basic Books.

Szasz, T. (1961). The myth of mental illness. New York: Hoeber-Harper.

Van der Toorn, J., Feinberg, M., Jost, J. T., Kay, A. C., Tyler, T. R., Willer, R., & Wilmuth, C. (2015). A sense of powerlessness fosters system justification: Implications for the legitimation of authority, hierarchy, and government. Political Psychology, 36, 93-110.