This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 100 years or less. Uploaded from Wikimedia Commons.

The picture above is taken from a sixteenth-century chronicle. The image depicts the sacking of a Russian city, Suzdal, by Mongol forces. The ruler of the Mongols in the West was Batu Khan. As the picture shows, the Mongols held a superior position, physically, because they were mounted on horses.

On November 28, 1240, the residents of Kiev huddled behind its fortifications. Outside the city, 20,000 Mongol warriors mustered. An ultimatum was issued: open the gates. Inside, stories circulated about other cities that had fallen and had been burned to the ground. The ultimatum was defied and a siege began.

Six days passed. The walls of the city were breached. The Mongols swarmed in and slaughtered 30,000 of Kiev's 50,000 inhabitants. With the fall of Kiev, the path to a Mongol invasion of Europe was open.

A modern observer might wonder, how did the people of the Steppe become such effective warriors? What qualities allowed nomads from the grasslands to overwhelm the settled communities that surrounded them? The story of the Mongol rise is as much about land as it is about people, for the people of the Steppe were shaped by the land on which they had survived since the Stone Age.

This is also a story of the horse, for without the horse the rise of the Mongols and the wave of invasions across Eurasia might never have taken place.

The Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe is a narrow span that stretches across almost one fifth of the globe. It is a vast grassland which runs nearly continuously from Hungry, across the belt of Central Asia, to Manchuria. In all it covers 5,000 miles from east to west and 400-500 miles from north to south. It is broken, almost in the middle, by the Altai Mountains, which go from the Gobi Desert to the West Siberian Plain. The sandstone bedrock of the Altai was a palette on which early people left images. These pictures were chiseled into rock that had been shaved smooth by glaciers.

West of the Altai lies the Western Steppe. Beyond the Altai, toward China, lies the Eastern Steppe.

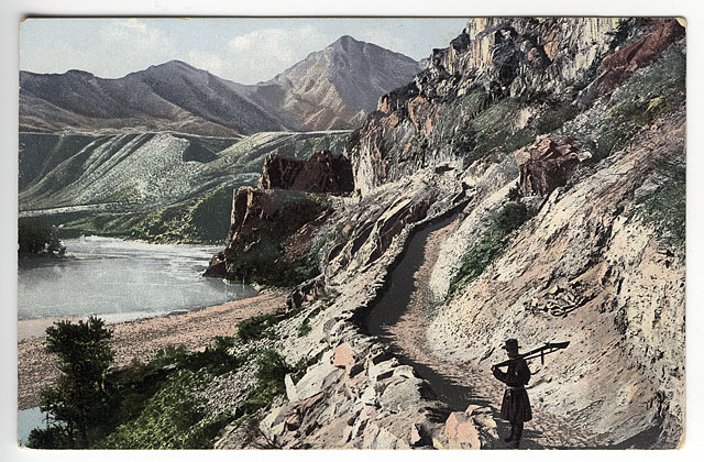

%20in%20the%20Altay,%20or%20Altai.jpg)

This picture, by Sergei Ivanovich Borisov (1867-1931), is in the public domain in countries where the copyright is the author's life plus 100 years.

Caption: This picture of the Altai Mountains (in Southern Siberia) shows the kind of rock into which early peoples of the Steppe chiseled petroglyphs. Often the art would be facing a river bank. The cliff in the picture is overlooking a point at which the Maly Eloman River flows into the Katun River.

At first, when a petroglyph is chiseled into the rock, it will leave a white impression. With the passage of time, this color would darken. A rough guess can be made about the vintage of a petroglyph by considering how deeply colored the image is. In the western Mongolian province of Bayan Olgii, for example, it is estimated that it would take about 3,000 years for a petroglyph to darken.

%20Damiano%20Luchetti%20free.jpg)

This picture was released into the public domain by the author, Damiano Luchetti

This picture of the Eastern Steppe was taken by in 1997. According to the caption, this shows the Mongolian-Manchurian grassland. A lone tree and river panorama are visible. Ordinarily, the soil and scarce rainfall do not allow for the growth of trees, but when a stream or river is present, trees may often be seen along the banks. The name of this river is not given in the caption. The image was released into the public domain.

The Steppe is characterized as arid to semi-arid. Annual rainfall is estimated to be between 25 and 50 centimeters, with more falling in the West than the East. Consequently, rolling expanses of grass characterize much of the Western Steppe, while sparse scrub characterizes much of the East. The Eastern Steppe is said to have one of the most severe climates on earth.

The geography of the Steppe has profoundly influenced successive cultures that arose on the central European plain. These cultures have in turn exerted extraordinary influence on surrounding communities. The Steppe cultures were largely, but not exclusively, nomadic. Because they were nomadic, they left meager archeological traces of their existence. Much of the durable evidence of these peoples and their lifestyle resides in the one state of permanence none of us escapes: death. Burial sites tell part of the story of the nomadic Steppe people.

Other clues about the belief system and values of early Steppe cultures may be derived from petroglyphs and pictographs. The pictographs were more vivid, because of the color they offered, but also were more fragile. These tended to be erased over time. Petroglyphs, however, abound. Many of these date back to the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Burial Mound

This work has been released into the public domain by its author, Barefact at English Wikipedia. This applies worldwide. Barefact grants anyone the right to use this work for any purpose, without any conditions, unless such conditions are required by law.

This burial mound (kurgan) is located in Fillipovka, Russia, in the southern Urals. It is believed to date from the fourth century BC. In a 2010 Field Report (published in the American Journal of Archeology), Leonid Teodorovich Yablonsky describes the excavations at Fillipovka, and their significance. In all, nine mounds were explored, the largest being for a royal personage. This mound yielded artifacts that were interred with the remains of a Sarmatian (fourth and fifth centuries, BC). The Sarmatians were early nomadic inhabitants of the Western Steppe. Their culture is often included in discussions of Scythians, a powerful, nomadic people described by Herodotus.

A fascinating insight offered by the Fillipovka mound excavations is the role possibly played by women in battle. Both female and male remains are buried in the mounds with "armaments and horse harnesses". This, Dr. Yablonsky suggests, might indicate that women rode into battle with men. Dr. Yablonsky also suggests, that these women may have been the models for Amazons described in ancient legend.

Soil of the Steppe

Though the Eurasian Steppe is in the temperate zone, the area is subject to extreme weather. Temperatures in summer can reach over 100º F, and in winter can plummet to 40º below zero. This severe pattern is more pronounced in the Eastern Steppe. The soil tends to be mineral rich and nitrogen poor. This, combined with low rainfall, inhibits tree growth but does allow for grasses and shrubs to flourish.

The ecology of the Steppe was not conducive to agriculture, but rather to herding. Thus the early inhabitants, for the most part, eventually established a pastoral lifestyle. They raised livestock and grazed horses. The need to find good grazing grounds was constant, for vegetation was consumed more quickly than could be replenished. Because of the greater availability of grasslands in the West, the inclination was to migrate in that direction. Barriers, such as other people, often needed to be overcome.

An interesting aside that demonstrates the value of pastureland to the Mongols: a story is told about Ogedei Khan, son of Genghis. Ogedei had just conquered Northern China. He contemplated slaughtering the area's inhabitants and turning Northern China into pastureland. His counselor, Yelu Chucai, suggested that people could pay taxes, and horses could not. Therefore, it would profit Ogedei to allow people to remain and work. This particular slaughter was avoided.

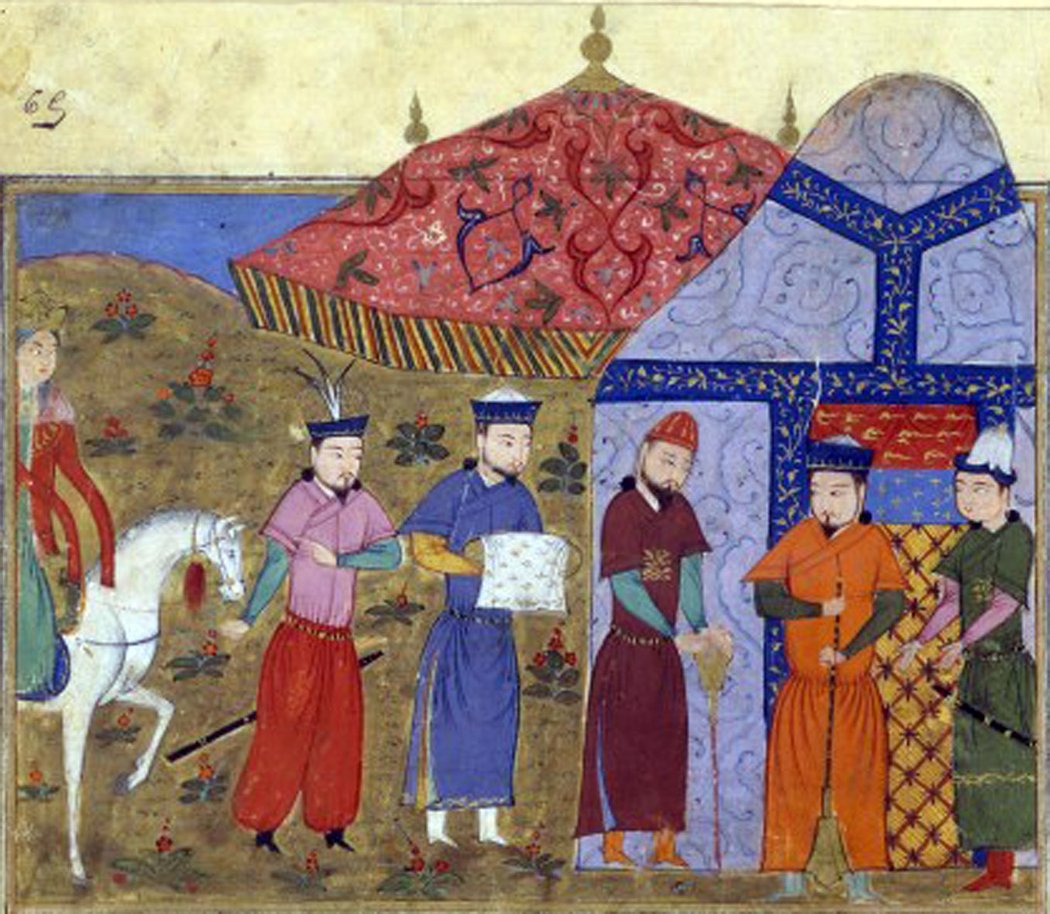

%20envoys%20Sayf%20al-V%C3%A2hid%C3%AE%201430.jpg)

This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 100 years or less. The image was created in 1430

This picture, which appears in a book by Sayf al-Vahidi, shows envoys of the Jin Dynasty (Northern China) offering tribute to Genghis Khan. Genghis Khan waged war against the Jin before Ogedei finally vanquished them in 1234.

Oases

While the Steppe is generally referred to as a grassland, an ethnobiological consideration of the area yields a more ecologically diverse picture. One research team describes ecotopes, which are sections of land that have outcroppings of rich vegetation, or even trees. These ecotopes are spread across the Steppe. Through examination of dung remains (!) from the Bronze and Iron Ages, the researchers conclude that survival for herding nomads was dependent on the resources of ecotopes. The herders would migrate to these well-known patches of vegetation for grazing.

The Horse

Of all the developments that shaped the lives of the Steppe nomads, the most significant may have been the domestication of the horse. Of course, it is difficult to separate this development from the environment that determined the rhythm of life on the Steppe. It was geography that made domesticating horses not only a necessity but almost an inevitability. With the domestication of the horse, nomads could roam with greater ease across the harsh terrain of the Steppe. They could cross over mountain passages. They could prevail in battle against opponents, who fought on foot.

The domestication of the horse on the Steppe is believed to have occurred sometime around 4000 BC. At the time, goats, pigs and cattle were already herded.

Lactase

A final break with a settled lifestyle was enabled when Steppe herders acquired the ability to digest milk in adulthood. Before this development, lactase, the enzyme that breaks down milk, was only present in infants. As an apparent physiological adaptation to their environment, the herders on the Steppe evolved to keep the enzyme throughout adulthood. Now a steady source of food could travel with the herders. They were no longer tied to farming in order to eat. It is believed this development occurred about 4,000 years ago.

As a interesting aside: lactose-tolerant people today--who have lactase as adults--inherited this trait from some ancient Steppe ancestor.

Rise of the Mongols and the Sacking of Kiev

And so we return to the huddled citizens of Kiev, and to other communities devastated by Mongol conquest. How did the nomad warriors prevail so consistently over their more settled adversaries? There are several reasons for their dominance. The Mongols were toughened and battle-readied by constant conflict between and within tribes. They rode on horseback. This gave them the ability to move swiftly in battle and to dominate over opponents on foot. Finally, a charismatic leader with extraordinary administrative and strategic skills, Genghis Khan, rose from their ranks. The Mongols were united and Genghis Khan gave them a single purpose. This they pursued without mercy.

The dominance of the Mongols came to an end, it is believed, with the fourteenth century plague pandemic. Ironically, it is suggested that the Silk Road, which ran across the Steppe, was a vehicle for transmitting plague, and it was a Mongol, Kublai Khan, who had made it possible for commerce to freely occur on the Road.

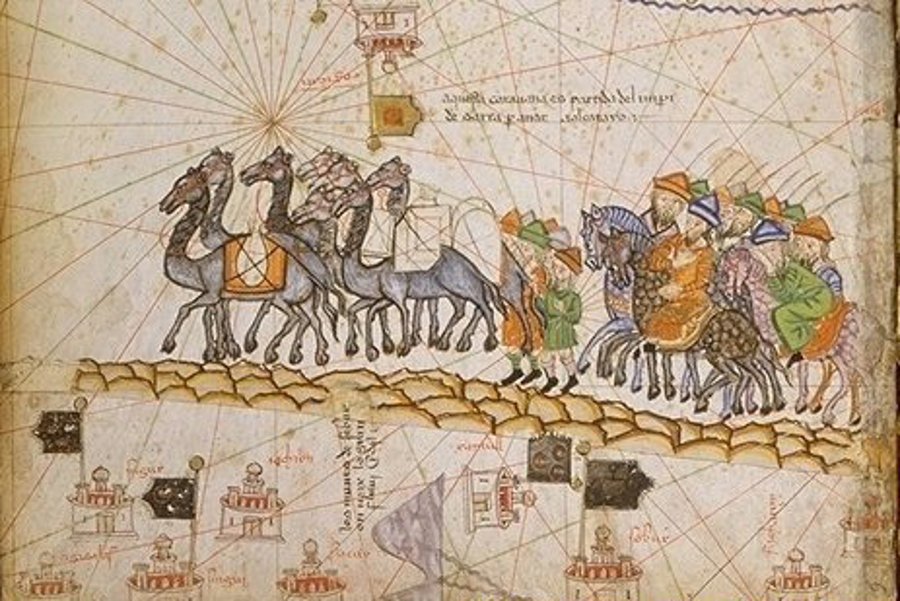

This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 100 years or less. The book was written in 1375.

This picture comes from The Atlas Catalan, which was created by Abraham Cresques in the fourteenth century. In the picture, a caravan is traveling along the Silk Road. The picture is in the public domain.