This is a sketch of James (William?) Morris, an American sailor who was committed to London's Royal Bethlehem Hospital (Bedlam), an institution dedicated to the care of the mentally ill. The sketch was originally rendered in black and white by George Arnaud (1763-1841) and then rendered in color by George Cruikshank. According to Graphic Arts (publication of Princeton University), Norris was admitted to the hospital in 1800. He behaved so badly that he was chained and remained that way for years, as shown in the drawing. The picture is in the public domain because its copyright has expired.

Ten-year-old Giovanna M. had a really bad headache. She consulted a doctor. He admitted her to a hospital where it was determined she was mad. Three years later she was sent to Sant’Antonio Hospital, an institution devoted to the care of the insane. The record is sparse on the course of Giovanna's treatment, but certain facts can be ascertained. She was consigned to the basement of Sant’Antonio, where she was chained with others judged to be mad. According to Giovanna's description, fifty people were confined in the basement, and these lived in their own excrement while rats gnawed on their open sores. At some point Giovanna was transferred to another hospital. She spent an indeterminate period of time there, but was eventually sent to Villa Clara, which was another institution devoted to the care of the insane. At Villa Clara she received the most "advanced psychiatric therapy", which included purges, tonics and insulin.

Finally, at the age of ninety, Giovanna was released: she passed away. She herself remarked that fate did not grant her the mercy of an earlier death. Her parting assessment: "Eighty years in a psychiatric hospital for a headache."(From Clinical Practice in Epidemiology in Mental Health).

Civil Hospital San Giovanni di Dio, Cagliari, where Giovanna spent time before she was transferred to Villa Clara. Image credit: Cristiano Cani. The photo is used under a Creative Commons-Attribution Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Unfortunately, in the annals of psychiatry, Giovanna's history is not extraordinary. This is a profession that no doubt has had many compassionate practitioners who strove to relieve suffering. However, with little understanding of the underlying causes of mental illness, these practitioners more often than not missed their mark. Today there is a movement afoot in psychiatry to bring clarity and an objective approach to the profession, by incorporating tools of hard science. This movement toward objective, evidence-based psychiatry has met resistance.

Throughout history, those suspected of being mentally ill have paid dearly for the lack of hard evidence to support their diagnoses. It was an awareness of this suffering that motivated one of psychiatry's severest and most capable critics, Thomas Szasz to do battle with the mainstream of his profession. Dr. Szasz once explained that, as a child, he realized there were two sorts of hospitals: hospitals people could get out of and hospitals people would never be able to leave. Dr. Szasz made it his mission in life to do away with the second sort of hospital--mental institutions. He wrote many books on this subject, one tellingly entitled, Coercion as a Cure: A Critical History of Psychiatry. Dr. Szasz believed that a diagnosis of insanity was merely a description of behavior that deviated from the norm. He did not believe deviation from the norm was a pathological condition, and he certainly did not believe that psychiatrists had the right to force a "cure" on anyone.

If we consider the record of psychiatry, we may find ourselves sympathetic to the Szasz perspective. With flimsy evidence, and often impelled by superstition, "healers" have imposed horrendous "cures" on countless patients over the centuries. Here I've listed a few of the more remarkable remedies. Each represented the wisdom of the medical community at the time.

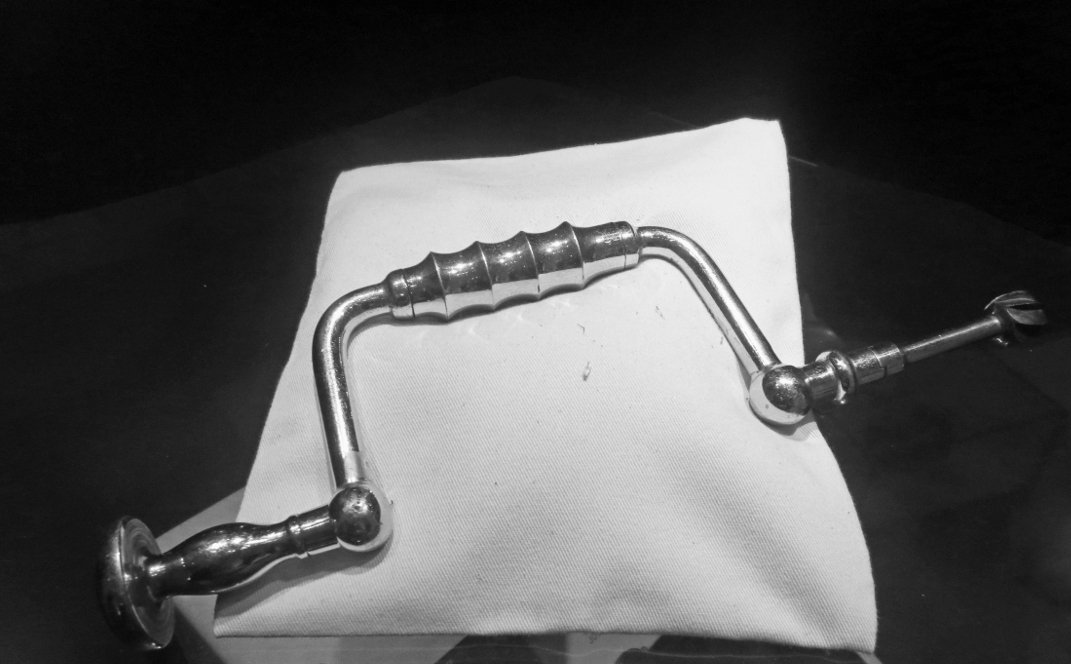

Lobotomy

This photo shows a drill that used to perform lobotomies on people in Norway. The procedure, according to the picture's caption, was performed in that country between 1942 and 1955. Picture is credited to: Bjoertvedt and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

This therapy has perhaps become more notorious in popular culture than any other psychiatric intervention. Most of us know that a lobotomy involves some sort of surgery on the frontal lobe of the brain. What may be surprising is that different doctors approached that operation in different ways. And lobotomies were not performed exclusively for psychiatric issues. The procedure received such general acceptance that it was used to treat back pain, arthritis and headaches.

The first lobotomy was performed by Antonio Egas Moniz, in Portugal. The year was 1935. For introducing this medical intervention, called at the time psychosurgery, Moniz won the Nobel Prize. The procedure, or some version of it, was performed on people of all ages. The youngest patient I came across in my reading was a twelve-year-old boy, Howard Dully. Although his personal physician judged the boy to be fine, his stepmother complained about his behavior. His bad acts included fighting with his brother, disobeying his parents and taking sweets without permission. The stepmother consulted Dr Walter Freeman, who thought a lobotomy was justified, and accordingly, in 1960, performed his famous "ice pick" procedure. Years later, Dully, in an interview with The Guardian, described feeling a sense of loss when he thought about his lobotomy, "like you've lost a whole part of your life".

Amazingly, lobotomies are still performed today in the United States, although the procedure is now called a cingulotomy,.

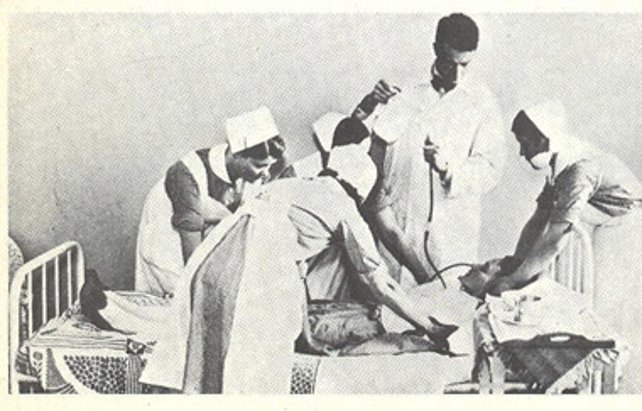

Insulin Shock Therapy

The caption under this picture explains that an insulin-induced coma is terminated by the introduction of glucose through a "gavage" tube. The scene shown in the photo took place in the 1950s, in a Helsinki hospital. The image is in the public domain.

It was an Austrian , Manfred Salek who came up with the idea of insulin shock therapy. In 1933 Salek started to use insulin-induced comas to treat schizophrenia. The course of treatment could include as many as sixty induced comas. Each of these insulin comas lasted about three hours and was reversed with the introduction of IV glucose. The practice was widely accepted in Western countries for about twenty years. It was eventually discredited, particularly after a controlled study in 1962 showed the treatment to be ineffective. Eventually, some analysts theorized that the calming effect patients seemed to experience after the course of treatment may have come from brain damage suffered during the coma. Estimates of mortality from the procedure vary. Once source suggests a mortality rate between 1 and 4%.

Trepanation

This illustration of a trepanation is from eighteenth-century France. The author is unknown, and the image is in the public domain because the copyright has expired.

Trepanation involves cutting holes in the skull. This procedure should not be confused with lobotomy. Lobotomy involves cutting into the brain and excising tissue or merely scrambling part of the frontal lobe.

Trepanation is an ancient practice used to treat both physical maladies and mental illness. In the case of mental illness, the logic of the treatment was clear. Demons possessed the mad. By drilling a hole in the skull the demons could be released and the patient cured. Trepanation was a widely performed procedure that many people survived. It is not known how many eventually succumbed to the effects of the surgery.

The Swing Chair

A 1792 portrait of Erasmus Darwin by Joseph Wright. Public domain image, expired copyright.

This invention was not in particularly widespread use, but it is included here as an illustration of how the supposed insane were powerless before the ingenuity of their keepers. The swing chair was the brainchild of Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin's grandfather. This distinguished physician noted that children were calmed when they played on a swing. So, he devised a box, open on one side, in which patients would be strapped and then twirled with such rapidity that they would experience vertigo, vomit and often lose their bowels. Patients subject to this 'treatment' were reported to show an improvement in behavior--it has been suggested that the improvement may have been due to apprehension about being subject to the "cure" once again.

The Triad of Twentieth-Century Psychiatry:

Psychoanalysis, Nosology, and Pharmacology

Together, these three tools have constituted the pillars of modern psychiatric practice, at least up until now. Each one of these pillars has played a critical role in psychiatry--although one of them, psychoanalysis, has fallen into less favor in recent years. Generally, a psychiatrist will use a combination of the three: symptom observation (nosology), talk (psychoanalysis) and drugs (pharmacology).

The three pillars, considered separately:

Probably the two most culturally influential figures of the twentieth century were Albert Einstein (Theory of Relativity) and Sigmund Freud (Psychoanalytic Theory). Einstein altered the way we regard the physical universe and Freud altered the way we regard ourselves. The first realm is the concern of physicists, the second the concern of psychiatrists.

This photo of Sigmund Freud was taken in 1920. The photo was shot by Max Halberstadt (1882-1940). The image is in the public domain because its copyright has expired.

Freud's effect on the practice of psychiatry in the twentieth century, and even today, cannot be overstated. Bertram Brown, one-time head of the United States National Institutes of Mental Health, once explained that for a time it was "almost impossible" in the US for someone to hold a chair or become a professor in an academic department of psychiatry unless they followed a psychoanalytic model in clinical practice. This psycho/social orientation--that is, viewing mental illness as a function of personal history and social context--led psychiatrists away from a biological consideration of mental illness. Psychosis was not a disease of the brain or body, it was a disorder of the psyche that could be rooted out by psychoanalysis--'talk therapy'.

II. Nosology

This refers to the effort, begun after WWII, to systematize the practice of psychiatry. The systematization began with the collection of data and grew to be a compilation of two massive diagnostic manuals--one, the ICD, issued by World Health Organization and the other, the DSM, issued by the American Psychiatric Association. Though the manuals were not identical they were periodically revised and there was an effort to reconcile them with each new edition.

This is the cover of a document prepared by the U.S. government that attempts to catalogue symptoms experienced by veterans of the Gulf War. It is the science of nosology which enables this sort of classification. While this document is neither the DSM nor the ICD, it does utilize the same methodology for diagnosis and treatment of illness. Since the image was produced by a U.S. government employee, the picture is in the public domain.

So far, since WWII, there have been five versions of the ICD and five versions of the DSM. In the most recent versions, the goal has been to offer psychiatrists a kind of checklist of symptoms that would lead to diagnostic consistency. The art of categorizing illness is called nosology. While clinical practice for most psychiatrists is governed by the categories described in the ICD and the DSM, a growing chorus of dissent has risen up from reputable quarters.

The three most serious criticisms lodged against traditional psychiatric methods of diagnosis are: A. Lack of reliability;* B. *Pathologization of "normal" behavior; and C. *Focus on symptoms, rather than causes of a disorder*.

These controversies explained, briefly:

A. Reliability: the same patient can consult three different doctors and may come away with three different diagnoses. The criteria from which the psychiatrists work, derived from the DSM (in the U.S.), are dependent on subjective impression and variability of patient presentation.

B. Pathologization: The sheer proliferation of categories has led to increased diagnoses, when many behaviors described as disorders are actually normal reactions to circumstances. Grief is one example often given to illustrate this point. The question is asked, how is a "normal", reasonable, response to loss distinguished from a pathological depression?

C. Separation from Causation: This last criticism is having the most profound effect on the direction of psychiatry today. Many critics point out that every other medical specialty supports diagnosis and treatment with concrete evidence--blood tests, computer imaging, genetic markers. Only in the DSM, the diagnostic bible for psychiatrists in the U.S., is evaluation and treatment prescribed based on a collection of symptoms alone.

This picture, by Craig Finn, shows what it feels like to have schizophrenia. Mr. Finn was reflecting his own perception of the world, as a patient who was being treated for the disorder. This remarkable picture was released into the public domain by Mr. Finn.

III Pharmacology

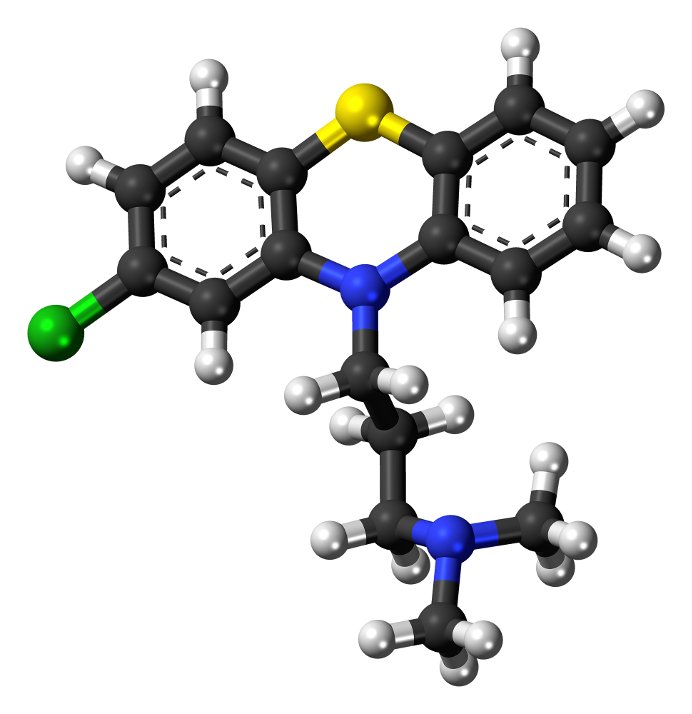

This is a model of a chloropromazine molecule. It is color coded: Carbon (C) -- black; Hydrogen (H)--white; Nitrogen (N)--blue; Sulphur (S)--yellow; Chlorine )Cl--green. The image has been released into the public domain by its author, Jynto.

In 1952 a drug called Chloropromazine went on the market in France. Its effect on the behavior of the recalcitrant mentally ill was obvious. People were calmed. Wards became quiet. This drug set psychiatry on a new path: psychopharmacology.. While the active mechanism for chloropromazine was understood (it blocked dopamine receptors in the brain) in most cases no one understood the way in which some of the other pharmaceuticals worked, though they did seem to work. The assessment of efficacy came from the fact that the behavior of some psychiatric patients, under influence of the drugs, was altered.

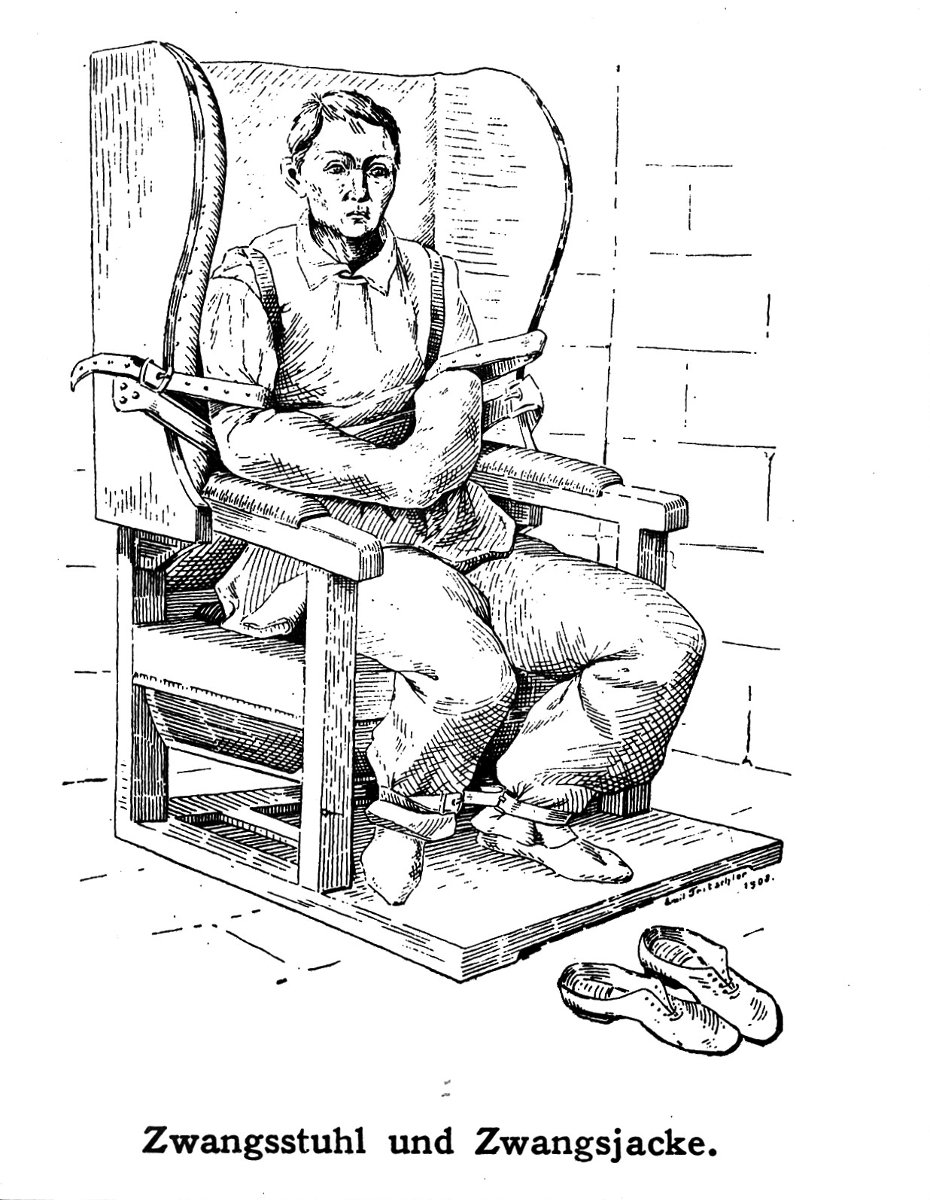

This image of a patient bound in an actual straight jacket comes from the Wellcome Trust.. The Trust is a repository of images that it offers freely if proper attribution is given. This drawing is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Over time, however, psychopharmaceuticals came under attack. Chloropromazine (better known as Thorazine), for example, gained a reputation for being a chemical straight jacket because of the numbing effect it had on patients. There were other reasons for the decline of this drug's popularity. It was discovered that serious, irreversible side effects could and did ensue from its use.

Unlike chloropromazine, some of the other antipsychotic drugs are prescribed without an understanding of the mechanism that leads to behavior modification. Two of the more commonly used are haloperidol and perphenazine. According to the description of haloperidol on Science Direct the " The precise mechanism of action is unclear". A similar description of perphenazine is found on DrugLib, which states "the site and mechanism of action of therapeutic effect are not known."

A Break with the Past: Biological Psychiatry, Neuropsychiatry

PET Scan

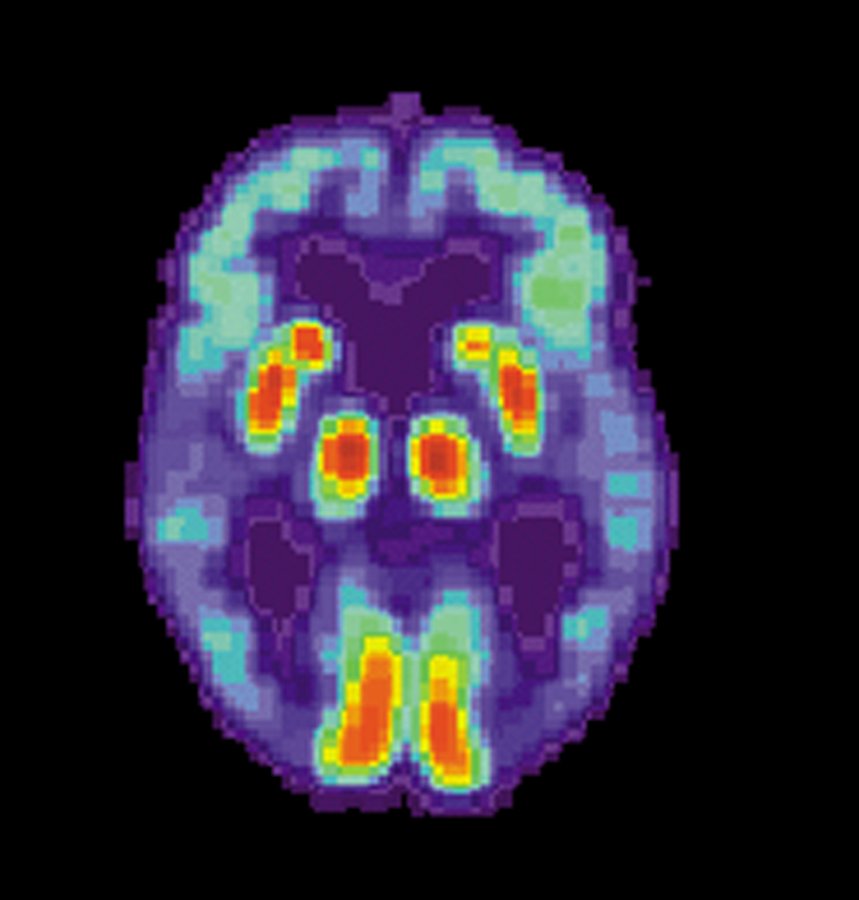

This image shows the PET scan of a patient with Alzheimer's Disease. The image was made by the U.S. government National Institute on Aging and is in the public domain.

In 2009, Paul R. McHugh, former Director of the Department of Psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Medical School, wrote an essay, Psychiatry at Stalemate, in which he took a sober look at the history and direction his profession had taken. It would be hard to find a more establishment figure in the field of psychiatry than Dr. McHugh. His assessment that psychiatry was in need of reform was all the more persuasive because of his stature. He points out something that is obvious to a lay observer: psychiatry treats symptoms but not causes. He explains that the "generative" nature of a disorder is not addressed in a course of treatment, just its expression. He asks, in his essay, what a patient is to make of a diagnosis that fits "criteria" for a disorder? Should the patient believe he is afflicted with a disease? Or is the difficulty the expression of an emotional state? In pinpointing psychiatry's lack of diagnostic clarity, Dr. McHugh highlights the major target of reformers in the profession. Although, to be sure, not all clinicians believe reform is called for. However, those that do want reform strive to bring psychiatry into line with the diagnostic methodology employed by other medical specialties.

Another influential voice for reform is Dr. Thomas Insel, previously Director of the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The NIMH is about as mainstream as you can get. Yet, when the most recent DSM was released, DSM5, in 2013, Dr. Insel expressed strong reservations. These reservations placed him at odds with establishment views. Dr. Insel explained that psychiatry does not do patients a service by focusing on symptoms which are entirely dependent on subjective reporting and observations. This diagnostic method is not reliable, in Dr. Insel's view, because it is not supported by physical evidence, or biological data.

This photo of Pilgrim State Hospital in Brentwood, New York, was taken in 1941. The hospital was designed as mental health facility, for the care and confinement of the mentally ill. Today, most of Pilgrim's grounds are closed, although part of the facility still treats patients. This image is from the Library of Congress, and according to the Library's records, the picture it is in the public domain.

Dr. Insel explained in a recent interview that without biomarkers, psychiatry lacks objective validity. The DSM, as it is now constituted, is merely a consensus document. In order to compile the manual, psychiatrists vote on what they think should be included and how it should be categorized. This becomes as much a political compromise as a medical guide.

Both Dr. Insel and Dr. McHugh, to varying degrees, address an issue that is the focus of a new sort of psychiatry. Called biological psychiatry, or neuropsychiatry, it involves a transdiagnostic approach. This incorporates traditional subjective factors with objective indicators such as computer modelling, "physical disturbances"(for example EEG results), and biomarkers (for example, indications of inflammation).

A researcher in the vanguard of neuropsychiatry, Daniel S. Barron, who holds both an MD degree from Yale and a PhD degree in brain imaging from the University of Texas, articulates the inevitability of wedding brain research to traditional psychiatric tools. Dr. Barron explains how knowing a patient's "neural hardware" can lead to understanding the underlying cause of symptoms and thus enable targeted treatment. He draws a comparison to another scenario, a patient with chest pain in an emergency room. The symptom of chest pain raises any number of possibilities. Medical history, social context (what were you doing when it started, for example), chest imaging and blood work are all helpful in arriving at a reliable diagnosis. It would be absurd to think the data derived from blood work, imaging and other objective tests were not essential to this procedure.

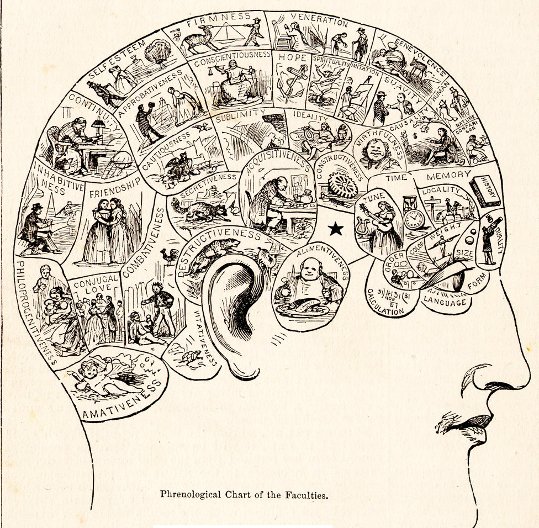

Phrenology was a "science" that was supposed to inform doctors about the human psyche. The shape and size of the skull were believe to reveal something about the character and personality of an individual. This image is in the public domain because its copyright has expired.

In a way, the new wave of psychiatry, which utilizes objective data to drive treatment and diagnosis, is a repudiation of all the horrors of psychiatry outlined in the first section of this essay. Early practitioners had no understanding of the physical basis of behavior. Their goal was to tamp down troublesome symptoms, at any cost. A cure was not a cure, but merely compliance. A lobotomy, Thorazine, and insulin shock may have had the effect of making patients more docile, but usually these treatments were at great cost to the patient and often the "cure" was not of long duration.

There are voices that caution against moving too quickly. The future of psychiatry as a science and branch of medicine is evolving. It behooves those of us who are not in the profession to pay attention, since some form of mental illness is likely to touch our lives, either directly or indirectly.

Some Sources Used in Writing This Blog

https://www.princeton.edu/~graphicarts/2010/01/an_insane_american.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3480686/

https://www.syracuse.com/news/index.ssf/2012/09/dr_thomas_szasz_critics_discus.html

http://www.centerforindependentthought.org/coercion_as_cure.html

https://listverse.com/2009/06/24/top-10-fascinating-and-notable-lobotomies/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4291941/

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2008/jan/13/neuroscience.medicalscience

https://www.medicalbag.com/despicable-doctors/walter-freeman-the-father-of-the-lobotomy/article/472966/

https://dublin.sciencegallery.com/failbetter/icepicklobotomy/

http://modernnotion.com/history-of-lobotomy/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Manfred-J-Sakel

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/13859190

http://frontierpsychiatrist.co.uk/things-that-have-given-psychiatry-a-bad-name-2-insulin-coma-therapy/

https://www.tititudorancea.com/z/insulin_shock_therapy_58.htm

http://home.wlu.edu/~lubint/touchstone/2000/Trephination-Chew.htm

https://www.cvltnation.com/horrifying-psychiatric-treatments-from-the-age-of-reason/

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/Edarwin.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2783473/

https://www.simplypsychology.org/psychoanalysis.html

https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/drugs-and-treatments/antipsychotics/

https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/einstein/einstein-s-revolution/

https://www.dw.com/en/freuds-pivotal-role-in-understanding-the-mind/a-1992871

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/index.shtml

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a544/53fa8ce0083c9c4a4aaf89ade3bd13b0251f.pdf

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2783473/

https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/history-of-the-dsm

https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/436403

https://blogs.cdc.gov/inside-nchs/2013/04/18/nosologists-what-do-they-do-and-why-is-it-important/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26098046

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24470508

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2013/transforming-diagnosis.shtml

https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/drugs-and-treatments/antipsychotics/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2655089/

https://www.ascpp.org/resources/information-for-patients/what-is-psychopharmacology/

https://www.coursehero.com/file/p6ku5tq/15-What-is-a-chemical-straitjacket-Chlorpromazine-Thorazine-was-the-first-and/

https://www.medicinenet.com/chlorpromazine_tablets_liquid-oral/article.htm

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/haloperidol

http://www.druglib.com/druginfo/perphenazine/description_pharmacology/

http://www.dana.org/People/Authors.aspx?id=37752

http://www.dana.org/Cerebrum/2009/Updating_the_Diagnostic_and_Statistical_Manual_of_Mental_Disorders/

http://healthland.time.com/2013/05/07/as-psychiatry-introduces-dsm-5-research-abandons-it/

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/892473

https://www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/

http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/neuropsychiatry

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wps.20514

https://medicine.yale.edu/psychiatry/education/residency/about/daniel_s_barron.profile

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/why-psychiatry-needs-neuroscience/

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/15/opinion/theres-such-a-thing-as-too-much-neuroscience.html

https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-By-the-Numbers