The picture shows a mountain lion peering out at a photographer. Mountain lions go by many names, including puma, cougar and panther. All of these cats belong to the concolor species,. The animals may be found wandering wild (though no longer in great numbers) across regions in Canada and the United States. According to a report issued by the US Geological Survey, a high percentage of concolors test positive for the parasite T. gondii. This is the organism that causes the zoonotic disease, toxoplasmosis.

The picture is credited to Larry Coats of the US Fish and Wildlife Service (public domain).

A domestic cat

This image was released into the public domain by its author, George Chernilevsky.

Recently I read some thoughtful blogs on Steemit about toxoplasmosis (authors credited in "Sources" at the end of this post). I did a little research and came up with a few ideas I'd like to add to the discussion. Here goes:

If you search for 'toxoplasmosis' on Steemit, you're bound to come up with alarming information about cats. These furry household favorites, it seems, are sometime purveyors of an insidious parasite,T. gondii. An infected cat may shed T. gondii in the family home, and potentially spread the disease, toxoplasmosis, among family members.

When the process of disease dissemination is described, one fact is often repeated: It is in the cat, and only in the cat, that the parasite T. gondii reaches sexual maturity and completes its life cycle. A search on Google, for "toxoplasmosis and cats", will likely yield the same result. From these search results, it would seem reasonable to assume that, if there were no more cats, there would be no more toxoplasmosis.

Not exactly. T. gondii is an inventive survivor and has devised a neat way to get around its cat problem.

Asexual Reproduction

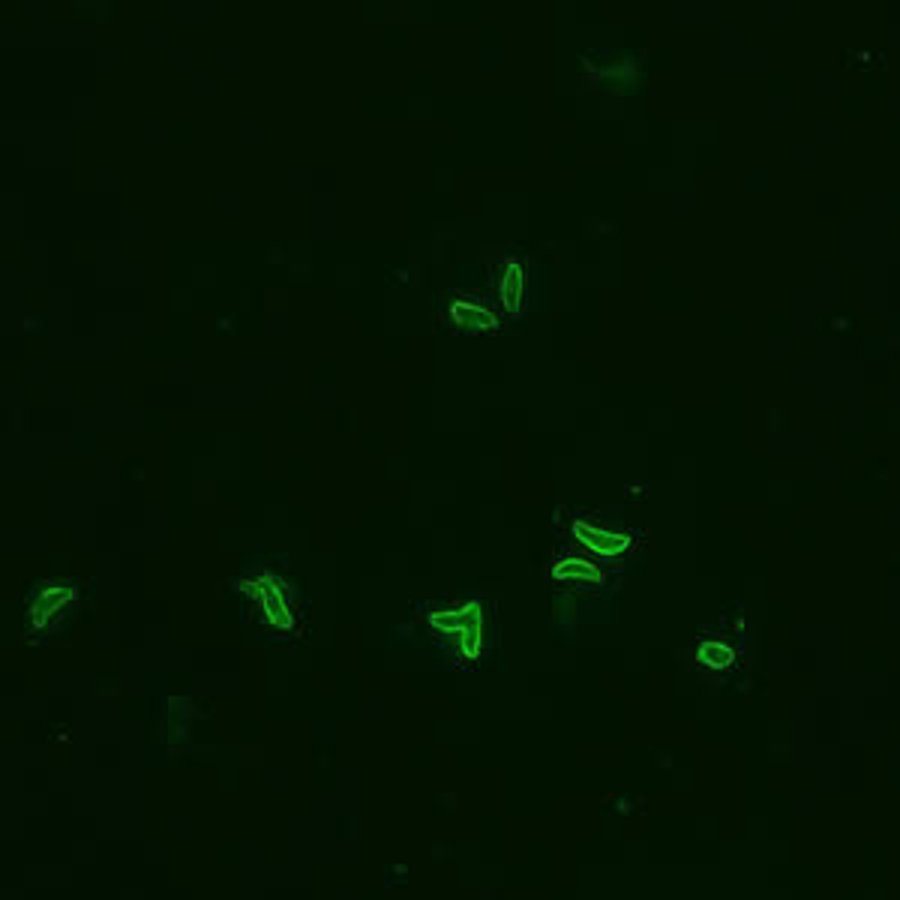

The image above shows rapidly replicating T. gondii tachyzoites. The tachyzoite is an intermediate stage of T. gondii asexual reproduction. Tachyzoites mature into bradyzoites. The growth of T. gondii slows down during this stage. The bradyzoite is encapsulated in a cyst. In this state, the parasite can usually resist a number of assaults, including those from the host's native immune system.

Image source: United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention: public domain.

T. gondii yearns to be in a cat's intestines, where it can mature and "complete its life cycle". However, the parasite has alternative strategies. It reproduces asexually if it can't find a cat. It does this in an "intermediate" host. In this less-desired host, the parasite can continue to infect warm-blooded animals without ever touching base with a cat. According to a research paper published in Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, asexual reproduction of T. gondii outside its preferred host (the cat) can proceed "ad infinitum". The parasite reproduces by cloning. The only downside to cloning for T. gondii is possible frustration :) and loss of genetic diversity, which sexual reproduction enables. Of course, genetic diversity is very important in evolutionary adaptation.

The beautiful bird in the picture is a pigeon from Kowloon, China. The bird is a delicacy on restaurant menus in Kowloon. It also is a potential source of toxoplasmosis. A 2012 article published in the online journal, Parasites and Vectors, reported that T. gondii was discovered in tissue samples taken from chickens, ducks and pigeons in Lanzhou, China. The animal specimens were purchased from a market where local people shopped for dinner. The authors of the article conclude that the prevalence of T. gondii in consumer meat "poses a potential risk for T. gondii infection in humans." Please note, the only way a cat would enter this picture is if it managed to get a piece of undercooked meat from the dinner table. Image credit: Citycat at Chinese Wikipedia, who has released the photo into the public domain.

As far as finding a suitable "intermediate" host, just about any warm-blooded animal will do. Birds, people, dogs, cats, mice, and many others, will serve. So it's not just cats that carry and introduce T. gondii into the environment. We all do. If every cat on the planet disappeared tomorrow, T. gondii would still thrive.

There's another problem with looking to cats in order to stop the spread of toxoplasmosis. When we speak of cats and T. gondii, we have to think big. Really big. Like lion and leopard. For T. gondii likes all felids, not just cats we find in our homes or out in the street. Blaming the house cat, or the "feral" cat for toxoplasmosis isn't a very productive exercise.

In 2015, the journal, Parasite, reported a fatal T. gondii infection in a giant panda at the Beijing Zoo. This was the first case of "clinical toxoplasmosis" in a giant panda recorded by the journal. This photo was released into the public domain by its author, Clute88.

Toxoplasmosis

T. gondii is "at least 10 million years old". It has survived, apparently, because it is extraordinarily adaptable. Numerous strains and subspecies have evolved over time.

The relationship between the mouse, the cat and the human seems to have occasioned a leap in the parasite's evolutionary development, and this occurred about 11,000 years ago, with the introduction of farming. Before this time, mice weren't much of a presence in human activity. However, with the growth and storage of grain, mice proliferated in human environments. Cats followed. The presence of cats was encouraged by humans because the felines controlled the proliferation of mice. With the establishment of a cat/mouse/human nexus, T. gondii was offered an opportunity, which it exploited brilliantly. Therefore, as is true in many cases where invasive species find a niche, humans played a significant role in the spread of toxoplasmosis.

Toxoplasmosis cyst in a mouse brain. From the journal Parasite. Authors:Carmen Anca Costache, Horaţiu Alexandru Colosi, Ligia Blaga, Adriana Györke, Anamaria Ioana Paştiu, Ioana Alina Colosi & Daniel Ajzenberg. The image is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Research indicates that mice infected with T. gondii show no fear of cats. This behavior suggests to some researchers that the parasite is actually manipulating the mouse so that it is more likely to be consumed by a cat. In this way, the parasite may complete its life cycle inside the cat's intestine.

This image of a pinyon mouse is in the public domain because it was prepared by an employee of the United States Park Service.

Perils of Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is one of the most widespread diseases on earth. A 2018 report suggests that 30% of the world's human population may be infected. The parasite can be fatal in immunocompromised individuals and can cause birth defects if a mother suffers an acute infection during pregnancy.

A female goat.

One route of transmission from animals to humans is raw (unpasteurized) goat's milk.. This image was released by its author Liserfern under a CC1.0 universal public domain license.

Effects on the Healthy

Generally, healthy people who are infected with T. gondii harbor the parasite with little consequence. However, a number of studies have suggested a connection between psychiatric syndromes and infection with T. gondii. The strongest association, it has been suggested, exists with schizophrenia. The studies that showed this association were not longitudinal. Which means there may have been discrete factors that influenced the results--for example, stressed people might be more inclined to own cats and therefore more likely to be infected with T. gondii (just an example of how outcomes might be distorted). Fortunately, there is at least one longitudinal study, carried out in New Zealand, and published in Plus One Journal that looked at the connection between behavioral issues and T. gondii. This study took a cohort of individuals, male and female, from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds (1,307 subjects) and followed them from birth until age 38. Over those years, the participants were periodically evaluated. The outcome of the study: "little evidence that T. gondii was related to increased risk of psychiatric disorder, poor impulse control, personality aberrations or neurocognitive impairment".

Of course, that is just one study, but it was one that followed standard study protocols.

Another, recent study (published 2017 in the journal Pathogens), with the suggestive title, Is Taxoplasma gondii a Trigger for Bipolar Disorder?, outlines the strong associations between various psychiatric disorders and T. gondii. However, buried in the middle of this article is one telling sentence: "...the role of infectious agents remains controversial, and to date, no clear cause-effect etiopathogenetic relation can be established." What this means is, association and correlation do not equal causation.

That said, T. gondii is prevalent in brain and muscle tissue of its hosts. In immunocompromised individuals (those with HIV, for example), toxoplasmosis can cause a vicious type of encephalitis. This, however, does not make the case that T. gondii causes either bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.

The Monk Seal

This picture of a Hawaiian Monk Seal was taken by Dr. James P. McVey for NOAA. As a work of the U. S. government, the picture is in the public domain.

One of the most emotionally resonating issues in the discussion of cats and T. gondii is the possible extinction of the Hawaiian Monk Seal. This marine mammal is listed as an endangered species. Recently, several of these seals have been found dead off the coast of Oahu from what seems to be toxoplasmosis. Cats on the island have been blamed for these deaths, because T. gondii is excreted in cat feces, and runoff containing feces washes into the sea. Therefore, the T. gondii contaminated runoff is presumed to have come in contact with seals. Many people believe, if cats were removed from the island, contamination of the water with T. gondii would cease and the endangered Monk Seal would be protected. This suggested course of action needs scrutiny.

As we have already established, T. gondii exists in many warm-blooded animals, besides the cat. These intermediate hosts include the rat, mongoose, mouse and bird. All of these are likely heavily infected with T. gondii. Of particular interest is the bird, because, according to OSHA, not only cat, but bird feces can carry T. gondii. Avibase ("the world bird database"), suggests that there are 233 bird species on Oahu.

Many sources exist that document contamination of beaches and parks with bird feces. One that addresses Hawaii in particular is entitled Microbial Load from Animal Feces at a Recreational Beach. In a book published by the University of Hawaii Press, Hydrology of the Hawaiian Islands, the authors state that duck feces and pigeon feces contaminate runoff from the land and beach in Hawaii.

It's probably true that runoff contaminated with cat feces in Hawaii carries T. gondii. But cats are not the only likely source. They are, though, the obvious source and the easiest target. An example of how they can be mistakenly targeted may be found in two Canadian episodes.

Port Alice, British Columbia, Canada. Author Sflostrand. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 International license.

A 1998 toxoplasmosis outbreak occurred in British Columbia. The source was water contamination, but, it was discovered cats were not the only culprits. Cougars were at least equally responsible. And, again, in 2018, deceased marine mammals in the Pacific Northwest were found to be contaminated with T. gondii, but the source was not just cats. It was also opossums.

So, while it is true that cats are the preferred ("definitive") host for T. gondii, they are hardly the exclusive candidates for spreading this parasite--on land or on sea. Perhaps, instead of indicting cats for carrying and spreading toxoplasmosis, we should target the parasite. This would seem to be a more effective approach. There is research underway to do just this, and the research has met with some success. Although there is no vaccine for humans, there are some that show modified utility in cats and mice.

The Tragic Story of Lyall's Wren

Sketch of a Lyall's Wren (also called Stephens Island Wren), by John Gerard Keulemans, 1895. The image is in the public domain because the copyright has expired.

The story is told of how Tibbles the cat extinguished the last Lyall's Wren on Stephen's Island, New Zealand. The story is true, sort of. Tibbles didn't single-handedly wipe out this species. There were other cats on the island. But none of these cats hired a boat to take them to Stephens Island. Humans introduced the cats to a pristine habitat, a habitat where flightless birds cavorted free of native predators.

According to fossil remains, Lyall's Wrens were once widely distributed across New Zealand. It is guessed that they were hunted into extinction by humans, as this predatory species expanded into new areas--everywhere except Stephens Island. In 1891, this refuge also became unsafe, when lighthouse construction was begun on the island. Shortly thereafter, humans brought cats to the preserve. This was the last gasp for the wren.

In light of this history, it's not reasonable to indict one cat, or a colony of cats, for the extinction of Lyall's Wren. The process of extinction was long and complex, and was due mostly to human activity. A recent National Geographic headline, New Zealand Announces Plan to Wipe Out Invasive Predators, highlights how the plight of the wren is similar to that of many native species. Endemic species in New Zealand have been in the bull's eye of invasive predators for generations. Most of these predators were introduced by, you guessed it, humans.

Well, there it is, my defense of the cat. While it is true that I love cats, circumstances in the past have also put turtles, birds, fish, dogs, and even mice in my care. It might be said that I'm pretty much, though not entirely, species neutral.

I'd like to credit three excellent blogs that got me thinking about this topic:

- Toxoplasmosis is the Leading Disease-caused Death for the Endangered Hawaiian Monks Seals (Neomonachus Schauinslandi), Showing How Much Damage Cats Can Indirectly Do to the Wildlife, by @valth

- Will Toxoplasmosis Make You Like Cats? Let's Take a Closer Look at the Disease and the Parasite That is Responsible for It!, by @valth

- Mind Bending Effect Caused by Toxoplasmosis Might Have Made You Interested to Pursue Business!, by @conficker

Some Direct Sources for My Blog:

http://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/mountain-lion-puma-cougar

https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1389/pdf/circ1389.pdf

https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19120791

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC108598/

http://mmbr.asm.org/content/64/3/607.full

http://parasite.org.au/para-site/text/toxoplasma-text.html

https://greengarageblog.org/20-big-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-asexual-reproduction

https://www.theage.com.au/education/variation-is-genetic-key-to-survival-20080225-ge6rje.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/01/travel/fare-of-the-country-pigeon-a-delicacy-for-cantonese-cooks.html

https://parasitesandvectors.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1756-3305-5-110

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1984-29612014000400547

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26514595

https://agresearchmag.ars.usda.gov/2008/sep/toxoplasma/

http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0037-86822017000400580

http://www.pnas.org/content/115/29/E6956

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/once-a-toxoplasma-parasite-infects-mice-they-never-fear-cats-again-9757150/

http://www.waterpathogens.org/book/toxoplasma-gondii

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5343064/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4046541/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5645871/

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxoplasmosis/gen_info/faqs.html

https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10091351

https://www.neuroscientificallychallenged.com/blog/toxoplasma-gondii-human-behavior

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4669300/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4757034/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5371891/

https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/4/adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infection/322/toxo

http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/13654/0

http://manoa.hawaii.edu/hpicesu/DPW/AS_THESIS/07.pdf

https://www.osha.gov/pls/imis/generalsearch.citation_detail?id=314314121&cit_id=01001

https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?region=UShioa

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2771205/

Hydrology of the Hawaiian Islands,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9576522

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/parasites-from-cats-and-opossums-found-in-dead-marine-mammals/article580829/

https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/07/new-zealand-invasives-islands-rats-kiwis-conservation/

http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/lyalls-wren

http://www.newzealandlighthouses.com/stephens_island.htm

*The purplish cat image at the end of the blog was created with a Microsoft 3D Paint program.