A mummified Egyptian head sat largely unknown for nearly 100 years, preserved in the basement of a medical building – but now, researchers have restored the identity of the young woman who lived 2,000 years ago

WHO WAS MERITAMUN?

The researchers say the mummy’s real name was lost long ago, so they’ve named her Meritamun, which means ‘beloved of the god Amun.’

It’s thought that she stood about 5 feet 4 inches tall, and was between the ages of 18 and 25 when she died.

The researchers are waiting on the results of radiocarbon dating to determine her true age, but they say the mummy may date as far back as 1500 BCE.

Analysis of the scans revealed that Meritamun had two tooth abscesses, and patches on the skulls where the bone had thinned indicate she was anaemic.

While the lack of other body parts to study prevents the researchers from knowing exactly how she died, this condition would have caused Meritamun to be pale and lethargic at the end of her life.

It remains unclear how the mummified head first came to the University of Melbourne, but researchers are now working to find out more about the life and death of the ancient woman, including when she lived, what diseases she had, where she was from, and what she ate.

Tooth decay in the ancient skull suggests she may have lived after 331 BCE, when sugar was introduced as a result of Alexander’s conquest of Egypt.

But, they say honey could also have caused this condition, and the mummy could date as far back as 1500 BCE.

As her real name was lost long ago, the team has decided to call her Meritamun, translating to ‘beloved of the god Amun.’

It was previously thought that the head may have decayed from the inside, meaning removal of the bandages could cause severe damages.

But, the CT scans revealed this was not the case – the skull was found to be in ‘extraordinarily good condition.’

‘The idea of the project is to take this relic and, in a sense, bring her back to life by using all the new technology,’ says Varsha Pilbrow, a biological anthropologist who teaches anatomy in the University of Melbourne’s Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience.

‘This way she can become much more than a fascinating object to be put on display.

‘Through her, students will be able to learn how to diagnose pathology marked on our anatomy, and learn how whole population groups can be affected by the environments in which they live.’

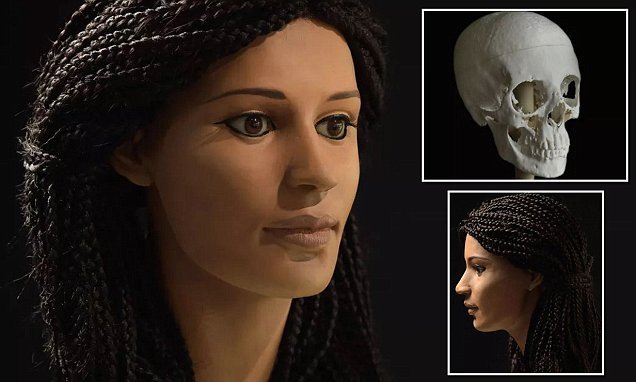

Experts conducted CT scans and 140 hours of 3D printing to reconstruct the face of ‘Meritamun,’ combining medical research with forensic science, Egyptology, and art to ‘bring her back to life’

Experts conducted CT scans and 140 hours of 3D printing to reconstruct the face of ‘Meritamun,’ combining medical research with forensic science, Egyptology, and art to ‘bring her back to life’

HOW THEY DID IT

The researchers used computerised tomographic (CT) scanning and a consumer-level 3D printer to reconstruct the skull.

Gavan Mitchell, an imaging technician from the Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience, printed the skull in two sections to optimize detail in the jaws and base of the skull.

Then, with the printed skull as a base, sculptor Jennifer Mann constructed Meritamun’s face.

This was done by attaching plastic markers at different points on the skull to mark varying tissue depths at key points, based on population averages.

The sculptor then applied clay according to the musculature of the cage and ratios of the skull.

While the nose on the mummified head had been squashed by the bandaging, the researchers were able to estimate its shape based on the dimensions of the nasal cavity.

They determined Meritamun had a small overbite, and the CT scan results allowed them to estimate her ears.

Once this was configured, the reconstruction was cast in polyurethane resin and painted.

The team used a dark olive hue for Meritamun’s skin, and based her hair on that of an Egyptian woman, Lady Rai, who lived around 1570-1530 BCE.

The original specimen lies face up in an archival container at the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology in the School of Biomedical Sciences, and is tightly bound by bandages, blackened by oil and embalming fluid.

‘Her face is kept upright because it is more respectful that way,’ says museum curator and parasitologist, Ryan Jeffries.

‘She was once a living person, just like all the human specimens we have preserved here, and we can’t forget that.

‘The CT scan opened up a whole lot of questions and avenues of enquiry and we realized it was a great forensic and teaching opportunity in collaborative research.’

The researchers used computerised tomographic (CT) scanning and a consumer-level 3D printer to reconstruct the skull. The skull was printed in two sections to optimize detail in the jaws and base

The researchers used computerised tomographic (CT) scanning and a consumer-level 3D printer to reconstruct the skull. The skull was printed in two sections to optimize detail in the jaws and base

With the printed skull as a base, sculptor Jennifer Mann constructed Meritamun’s face. The team is also working to determine what Meritamun ate and where she lived based on carbon and nitrogen atoms in the tissue

With the printed skull as a base, sculptor Jennifer Mann constructed Meritamun’s face. The team is also working to determine what Meritamun ate and where she lived based on carbon and nitrogen atoms in the tissue

The head was scanned at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine, where forensic Egyptologist Dr Janet Davey, from Monash University, determined it was Egyptian.

And, based on the bone structure, including the size and angle of the jaw, the structure of the roof of the mouth, and the shape of the eye sockets, the researcher was able to determine the gender.

Davey, who previously restored the face of King Richard III, then confirmed the findings with another expert in the UK.

Analysis of the scans revealed that Meritamun had two tooth abscesses, and patches on the skulls where the bone had thinned indicate she was anaemic.

The researchers say this could have been caused by malaria parasites, including malaria or schistosomiasis, a flatworm infection.

While the lack of other body parts to study prevents the researchers from knowing exactly how she died, they say this condition would have caused Meritamun to become pale and lethargic at the end of her life.

‘The fact that she lived to adulthood suggests that she was infected later in life,’ says Stacey Gorski, a biomedical science masters student at the University of Melbourne.

‘Anaemia is a very common pathology that is found in bodies form ancient Egypt, but it usually isn’t very clear to see unless you can look directly at the skull. But it was completely clear from just looking at the images.’

The team is also working to determine what Meritamun ate and where she lived based on carbon and nitrogen atoms in the tissue, and radiocarbon dating will reveal just how old the mummy really is.

‘By reconstructing her we are giving back some of her identity,’ says Dr Davey, ‘and in return she has given this group of diverse researchers a wonderful opportunity to investigate and push the boundaries of knowledge and technology as far as we can go.’