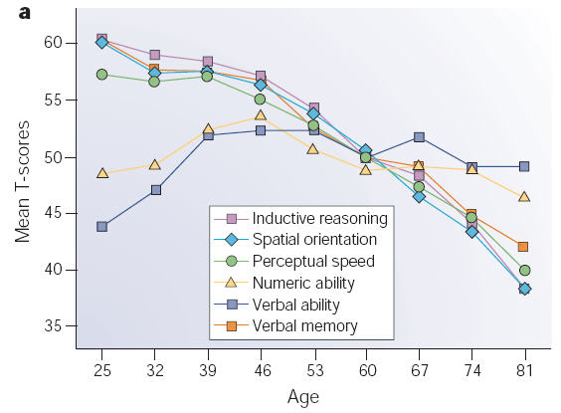

In my scientific field of cognitive aging, it is extremely common to see a figure similar to this one:

This figure represents the narrative of cognitive decline that you are most likely to hear, and in my view is an overly pessimistic one. The story goes something like this:

The trajectory of cognitive decline can be conveniently thought of in terms of Cattell’s ideas of “fluid intelligence” and “crystallized intelligence”. Fluid intelligence is composed of many cognitive domains that deal with flexibly manipulating information in novel situations without relying on previously acquired knowledge, whereas crystallized intelligence represents the ability to utilize experience and knowledge. On average, aging is accompanied by a decline in fluid intelligence starting as early as the mid-twenties. In contrast, crystallized intelligence, which relies much more on experience, actually improves with age. This is why leaders, who must rely on wisdom and experience, are typically older than their twenties.

That narrative, while effective at motivating a graduate student in their twenties like me to get busy solving this problem, may not be completely true.

This is because most of these graphs come from cross-sectional data, which means that the ages are represented by different people. Cognition is not followed across 60 years for each individual, but instead, different age-cohorts are used to find the averages of cognitive performance for each age group.

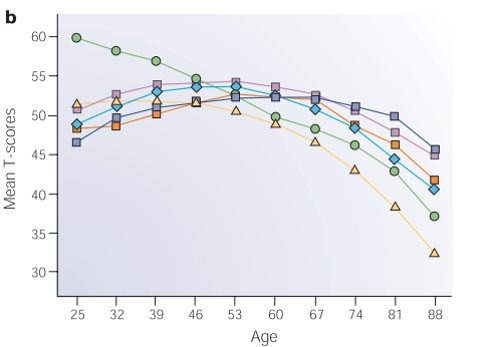

When we look at longitudinal data, a different picture appears. Longitudinal data represents data that is measured from a participant over time. The figure presented here does not have 60 years’ worth of longitudinal data, but does have much longer stretches than the cross-sectional data above

According to this figure, perceptual speed does seem to decline consistently from the early twenties. However, much of the other “fluid intelligence” cognitive domains, such as inductive reasoning and spatial orientation, continue increasing into the 50’s or 60’s. Also, verbal ability, a crystallized intelligence task, now also drops, instead of staying stable into old age like it did in the cross-sectional sample. I am partial to this longitudinal data because it gives me a bit more time to work on fixing the problem, but in truth, most likely both of these pictures are incorrect.

That is because both cross-sectional and longitudinal designs have weaknesses that bias the results of scientific studies.

Cross-sectional designs primarily suffer from cohort effects, which can be especially bothersome in aging studies. This is partially because there are large differences between age cohorts that may affect the performance on cognitive tests. Other factors may lead to non-representative cohorts. For instance, most academic institutions most easily recruit students that attend that institution. In addition, elderly subjects who choose to participate in a research study are necessarily mobile enough to make it to the experiment and likely to be engaged and interested in science, which may select for a non-representative portion of that population. Middle aged individuals who can participate in research experiments may be more likely to not have a day job that would otherwise prevent them from coming to the lab during normal work hours.

Longitudinal designs may look more convincing because cognitive performance is followed over the lifespan. However, these designs suffer from their own drawbacks. First, it is difficult to control for training effects, which will inevitably occur if the participant is frequently being tested on similar cognitive tasks. The researcher needs the tasks to be similar, so that they can compare the participant’s performance over time, but in many tasks, improvements due to practice are expected. Another issue is attrition, and particularly attrition that could be caused by some confounding factor. In aging studies, it may be more likely for an older participant who is suffering from cognitive decline to drop out of the study, thus artificially inflating the performance of the group as a whole.

Cognitive aging is not a set in stone. Whatever the true average trajectory is, recent research has demonstrated a telling and hopeful fact: that cognitive decline is highly variable between and plastic within individuals. Understanding that variability will help us strive forward towards improving cognitive outcomes in older age.

Figures from:

Hedden, T., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2004). Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(2), 87–96.