The average human produces a litre of sweat every day, so in a world of ever-mounting social pressures it's no surprise that, since the first commercial deodorant in the late 1800's, personal hygiene industries - deodorants and soaps in particular - have flourished.

Unlike their primitive counterparts, many modern day deodorants do more than just mask odours with a fragrance.

Why Do We Sweat?

The most crucial role sweating plays in human physiology is cooling to maintain a constant core temperature (homeostasis).

Sweat, a mixture comprising mainly water, minerals and oils, takes heat with it as it evaporates from the skin, cooling the body's surface temperature down as it does so.

Apocrine glands, unlike eccrine glands, are not always stimulated by heat alone; anxiety, stress and hormone fluctuations can trigger excretion...

Sweat ≠ Stench

Humans, like many species of animal, stink by design.

In the wild, a pungent smell can be useful, acting as a deterrent to predators or an allure to prey, but, in modern-day society, body odour is a source of embarrassment.

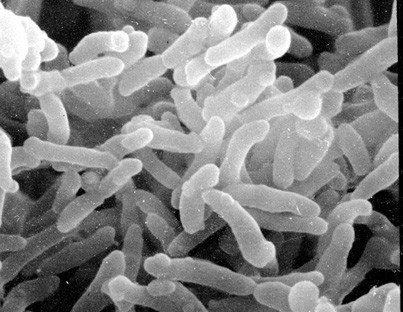

However, our sweat excretions are not directly responsible for body odour. Instead, we have the fermenting effects of the human microbiota, colonies of foreign microorganisms, to thank for our scent.

Bacteria, present in droves in the smelly underarm and genital regions, can - like most microorganisms - be useful to us (stimulating immune response systems and maintaining skin pH balance, for example).

However, certain species - Corynebacterium in particular - break components of apocrine-produced sweat into acids, many of which have a foul odour - propanoic, butyric and trans-3-methyl hexanoic acid are all common culprits.

This, combined with the wicking, aerating effect of wiry armpit/pubic hair, leads to body odour.

Antiperspirants

For a long time, the only solution to natural body odour was washing regularly.

However, as alkaline hygiene products were developed to better cut through grease and dirt, some oft-used modern day soaps began to exacerbate hygiene problems.

The problem? Long-term use of alkaline soaps strips the skin off its most valuable defence to many bacteria: acidity.

The natural pH of skin is around 5.5, meaning alkali-loving microorganisms struggle to survive. A small shift in acidity allows these bacteria to proliferate, significantly upping odour output.

A new, more robust solution was required.

Enter antiperspirants.

Fragranced deodorants of varying origins had been around for many hundreds of years, but their purpose had been to mask rather than eliminate odour.

In 1941, American Jules Montenier patented the first antiperspirant, which claimed to reduce the amount a wearer sweats, thereby eliminating the moist environment in which bacteria thrive.

The active ingredient in antiperspirants today is typically an aluminium salt, usually aluminium chlorohydrate or an aluminium zirconium compound.

The salt reacts with electrolytes in sweat to form a gel, plugging the skin's pores and preventing secretions from escaping.

A secondary mechanism of action encourages contraction of the pores - an astringent effect - further hindering sweat release.

Safety Concerns

Since their conception, there have been multiple health scares surrounding antiperspirant use, often regarding long-term exposure to aluminium compounds.

Aluminium is feared to be toxic in high doses, affecting the blood-brain barrier and damaging DNA.

Following an investigation, the Food and Drug Administration concluded:

Despite many investigators looking at this issue, the agency does not find data from topical and inhalation chronic exposure animal and human studies submitted to date sufficient to change the monograph status of aluminium-containing antiperspirants.

Unfounded and fictitious health concerns have also arisen, such as the rumour linking aluminium salts to breast cancer, thought to have originated as a hoax email.

Going Au Natural

There's a case to be made for ditching the roll-on. Research suggests that quantity and composition of sweat can be altered by dietary and exercise improvements.

What's more, antiperspirants may inhibit more than just sweat production; the secretion of pheromones, the evolutionary chemical markers we use to attract potential mates, may be affected in a similar way.

If you enjoyed this article and would like more, follow the everyday science blog for your daily dose of science.

References:

Chemistry 4th Edition by Housecroft & Constable

www.thefactsabout.co.uk

www.wikipedia.org

www.mentalfloss.com

James May's BBC Earth Lab