When I tell people I work with reptiles, many immediately recoil in disgust or fear. They don’t think about the turtles, crocodilians or lizards, but their minds go directly to the poor snakes. They imagine a deadly snake, like a cobra or a rattlesnake, reared up and exposing its fangs ferociously (luckily, snakes, and even venomous snakes, are generally not like that at all). Despite their fearsome reputation, venomous snakes (and lizards) actually do far more good than harm, and that is all thanks to the miraculous substance we call venom.

So just what exactly is venom and how did it come to be in reptiles?

A reptile’s venom is actually modified saliva carrying a variety of proteins, toxins, and polypeptides that serve a number of purposes. Venom may be used to kill or subdue prey, for diet-relation functions or even as a form of defense. There are four basic types of venom that attack the body differently. Proteolytic venom destructs the molecular structure of the bite wound and surrounding area. Hemotoxic venoms target the heart and cardiovascular system. Neurotoxic venom affects the nervous system and brain. And cytotoxic tissues cause intense pain by destroying tissues by eating away at the flesh. So that's some pretty nasty stuff.

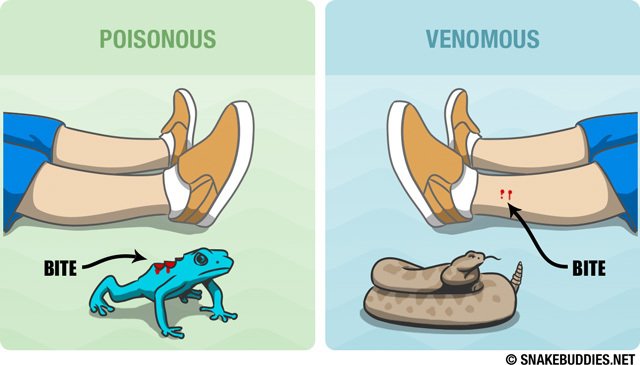

CreditVenom and poison are similar in function and structure, but differ in their delivery mechanisms. Poison must be ingested or absorbed through physical contact from animals such as toads or butterflies. Venom is injected in prey, either through a sting, fangs or sharp spines, by animals such as snakes, jellyfish and scorpions.

Recent gene sequencing has found that the earliest (extremely primitive) venoms observed in snakes contained proteins similar to those found in lizards, suggestion that venom originated only once in their entire lineage – roughly 170 million years ago. This venom was extremely simple, comprised of only a couple proteins created by a pair of primitive venom glands. From there, the venoms and the delivery mechanisms of the different lineages diversified. This origin of venom is suspected to be what made the rapid diversification of snakes during the Cenozoic period possible.

In some species, the venom glands atrophied or disappeared entirely. Many snakes lost their ability to produce venom when they developed another technique for subduing prey: constriction.

Many snakes inject their venom through fangs; delivering their venom in a fashion reminiscent of a hypodermic needle. Some lizards, like the gila monster, bite down and chew on flesh, drooling their venom messily into the open wound. And some, like the spitting cobra, are able to force venom through their teeth, allowing them to accurately spit toxins several meters to blind their target!

A few snakes, such as the copperhead, are not all that potent to humans despite being classified as venomous. This is because most venomous species actually tailor their venom to be more toxic to the prey species that dominate their diets, and may not be as harmful to non-target species!

A recent study revealed that venom can also be used to track prey that has been bitten. Many snakes, like rattlesnakes, bite and release their prey extremely quickly, to avoid confrontation with potentially dangerous animals. Once the prey has been bitten, it attempts to flee, while the snake tracks it, waiting for the venom to take effect. Using a process known as prey relocalization, western diamondback rattlesnakes (and their kin) are able to track the venom in the prey’s system. The 2013 study found that the snakes responded more actively to mice carcasses injected with venom, and were better able to track the prey than mice that had no traces of venom.

Venom has become one of the deadliest and most useful tools in the animal kingdom. It's development gave snakes a clear advantage over their prey, allowing them to diversify rapidly. Fortunately, through breakthroughs in medical research, we have already begun to harness the power of venom for good. Snake venom is used to treat many conditions, from blood pressure to strokes and heart attacks. As fearsome as venomous snakes may be, their remarkable venom may just save a life.