The concept of free will existing is a dramatic misconception. While we feel that we might be able to do whatever it is we want, or say whatever we want; we can combine several scientific studies and research, providing some strong evidence that free will cannot possibly exist.

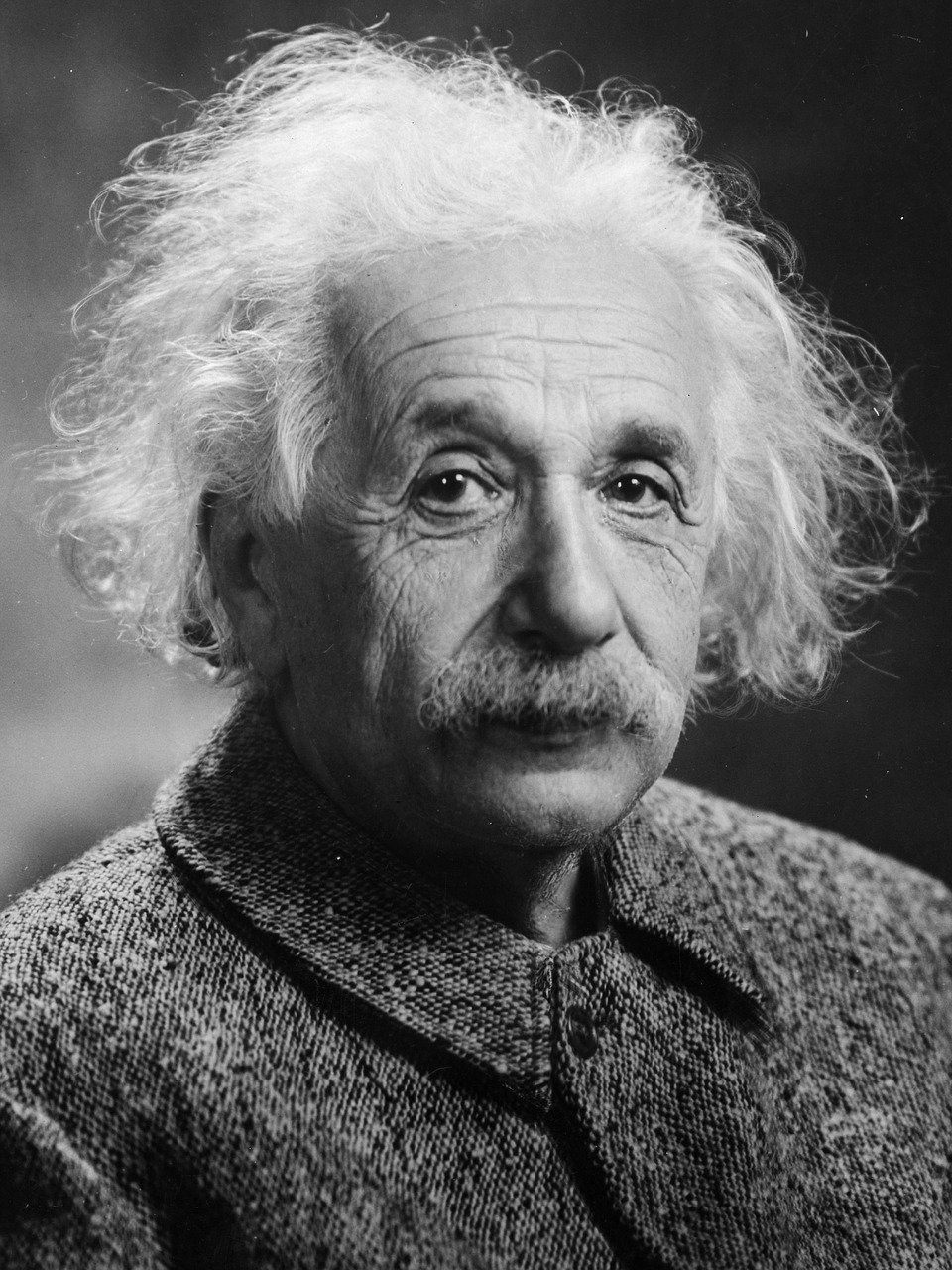

Let's start wtih how the Brain works. Its not rocket surgery. Neurons make up the human brain and nervous system, and are responsible for the electro-mechanics of life. When a neuron wants to interact with other parts of the body, it will send an electrical message onward, that will be inepreted, and result in an action. There's about 86 billion of these in our bodies1, which means that there's an almost unfathomable number of electrical signals flying around the body at an atomic level.

A Neuron [Source]

There's a grand total of about 7,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms that make up a human body.2 That is a lot of chaos going on. Somehow, all those elemental atoms enable our ongoing existence, and enable me to write this, and you to read this.

I'm not smart enough to explain the exact mechanics of how a neuron works, so here's a direct quote from Wikipedia, regarding their conductivity:

All neurons are electrically excitable, maintaining voltage gradients across their membranes by means of metabolically driven ion pumps, which combine with ion channels embedded in the membrane to generate intracellular-versus-extracellular concentration differences of ions such as sodium, potassium, chloride, and calcium. Changes in the cross-membrane voltage can alter the function of voltage-dependent ion channels. If the voltage changes by a large enough amount, an all-or-none electrochemical pulse called an action potential is generated, which travels rapidly along the cell's axon, and activates synaptic connections with other cells when it arrives.3

Electricity is created when there are electrons that have fled (or been wrenched) from their atomic home. Electricity flows along conductive matter, and can't travel (very well, along insulating matter); neurons have a coating that makes them conductive, enabling them to transmit their electrical impulses. The generation of an electrical impulse in a neuron, as above, occurs due to chemistry.

Electricity,, but not in the body. [Source]

Electricity,, but not in the body. [Source]An electron, impossibly small, isn't the only thing that makes up the universe, there's quantum particles that exist on the sub-atomic level, and incredibly; even in a vacuum, "There are quantum particles popping into and out of existence throughout the Universe. There's nothing, then pop, something, and then the particles collide and you're left with nothing again. And so, even if you could remove everything from the Universe, you'd still be left with these quantum fluctuations embedded in spacetime.4"

Can we then assume, if sub-atomic, quantum particles are flickering in and out of existence everywhere, throughout the universe (even in a vacuum); that perhaps these quantum anomalies would influence the action of our neurons, sending signals throughout our body that we can't control, or even think to do?

This involves some elaborate thinking, and combining the seemingly random nature of quantum mechanics with what we know about the function of the neuron. Albert Einstein said that "God does not play dice with the universe"; in confusion at Quantum Mechanics and theory. He was not comfortable with the idea that the universe was random and untamed.5Does this then mean that the entire universe is deterministic, instead of random? Quantum mechanics allows us to predict events based on the current state of things,6 and the likeliness of any particular outcome. The deterministic, classical view is that you can predict what is going to happen next. The quantum view is that you can only calculate the level of probability that something will unfold in a certain way.

If there's a high probability of something occurring, a Neuron firing; and this can be predicted by the models of Quantum Mechanics; then this is a death sentence for the very concept of free will. It can't possibly exist if there's a 70% chance of me going for a run, and a 30% chance of staying at home and being lazy. That's not free will at all, is it?

There's a very intelligent discussion on knowing neurons that explores whether the notion of free will exists or doesn't. There's huge amounts of study elsewhere in the scientific, psychological and philosophical archives of literature, and there is no proof one way or the other.

Quantum Mechanics is seen as one of the closest 'grand unifying' theories of the physical universe, but even with its incredible depth, we still can't determine if free will exists. There's arguments for, and arguments against, but we don't know enough yet to say one way or the other with 100% certainty. With what we do know, we can say, that our perception that we do have freewill, may be a misconception.

Sources

- The Univeristy of Queensland Brain Institute - "What is a Neruon?"

- Khan Academy, Matter, Elements and Atoms | Chemistry of Life.

- Wikipedia - Neruon.

- What is Nothing? Physics.Org

- One of Einstein's most famous quotes is often completely misinterpreted - Business Insider

- The Strange World of Quantum Mechanics - Dan Styer