"Larks", "night owls" and "hummingbirds"

About 10 percent of the population belong to the so called "larks", whereas 20 percent are "night owls". The rest is partly labeled as "hummingbirds", whereby some of them are more larkish, some more owlish.[1]

To be a morning (lark) or an evening person (night owl) respectively something in between (hummingbird), is called your chronotype.

I have always been quite an extreme night owl and therefore all along hated slogans like "The early bird catches the worm" or also in German "Morgenstund hat Gold im Mund", which imply that people who stand up early are more diligent, flexible, social and successful. Instead my own motto is "The early worm gets caught by the bird". :-)

Source: pixabay.

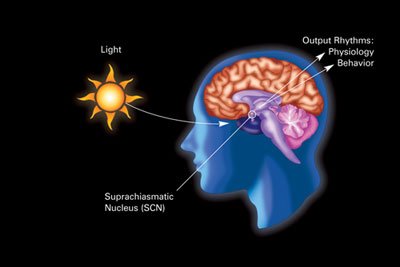

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) regulates our circadian rhythms.

|

Already long time ago scientists found out that most organisms with a life span of at least several days have circadian rhythms, that approximate the length of a day and a night. That enables them to anticipate the changes imposed by the alternation between day and night.[2] Our circadian rhythms are regulated by a paired master oscillator (controlling slave oscillators throughout the body) in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a region of the brain in the hypothalamus, situated directly above the optic chiasm.[3] |

By National Institute of General Medical Sciences - Circadian Rhythms Fact Sheet, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7408107 |

Whereas the average is reported to be 24.2 hours[4], the circadian periods of blind test probands showed a range of 23.83 to 25.00 hours.[2] (The phase of the SCN oscillator of individuals with normal eyesight is entrained by the external light/dark cycle.[5])

What are the reasons for the existence of different chronotypes?

As the studies above show, obviously diverging circadian rhythms cause individuals to be "larks", "night owls" or "hummingbirds", but what are the reasons for these differences?

"Not a morning person? Blame your genes, scientists say".[6] Many articles start similar like the above, and yes, indeed, even if not everything is fully understood yet, because the regulation of the circadian rhythm is a polygenic trait[7], at least we can say for sure that the individual varying combination of a certain number of genes (or more exact: alleles of these genes) is responsible for our chronotype.

Before I continue my article by presenting the results of a few research works regarding the effects of some involved genes, I would like to hold for a moment and go back to the opening paragraph: "Blame your genes, scientists say", blame? Am I a criminal, just because I prefer to get up later than the average guy and reach my maximum of activity in the afternoons, evenings or even at night? Are the genes of "larks" or "hummingbirds" also to blame, because they get tired so early in the evening? Does the value of work depend on when it has been done or is it still the result of the work what matters? Do "night owls" have to change their intrinsic rhythm of life and adapt to the extrinsic rhythm of a society dominated by a minority of "early birds"? I say "NO!", the society has to adapt and accept the peculiarities of the single individual, especially also because it is associated with quite some health risks to live permanently in contradiction with ones own circadian rhythm. For example it seems that not only a short sleep duration is a risk factor for obesity, but also "social jetlag" which means the discrepancy that often arises between circadian and social clocks.[8]

How exactly do genes influence our circadian rhythms?

First of all it should be emphasized that still a lot of work has to be done until we really understand the influences of all parameters which influence our sleep-wake cycles.

Many studies have been accomplished, and I can only present a few of them in a very short form:

-

M. von Schantz and S. N. Archer examined already in 2003 the effects of the Period (Per1, Per2 and Per3) and Cryptochrome (Cry1 and Cry2; where the term "crypto" should suits very well to an article written on this platform ...) genes on the circadian rhythms of mice.[2] They recognized that the concentrations of the proteins encoded by these genes fluctuate over the day-night period of 24 hours and reach a maximum during the middle of the night. The proteins build trimeric complexes (varying combinations of PER1/PER2/PER3 + CRY1/CRY2 + CK I) inhibiting the further transcription of their own genes in a complicated process (whereby they suppress the positive effect of another protein complex CLOCK:BMAL1). Slowly their concentration decreases, so that the genes are not inhibited any longer, and the cycle can start again.

The scientists found out that both, mutations in the different Clock genes and disabling of one or more types of the Per and Cry genes either altered the circadian period or abolished the rhythm completely.

-

Especially interesting in this context seems to be the gene Per3 which exist in form of two different alleles, whereas the longer one associated with morningness, and the shorter one with eveningness.[9]

Also newer studies hint at the importance of Per3 as "the primary circadian pacemaker in the mammalian brain".[10]

-

Panda and his colleagues at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have identified an "alarm clock gene". In the journal Science they describe how the gene KDM5A encodes an enzyme, JARID1a, responsible to activate cells and organs each morning.

Similar like von Schantz and Archer also the Salk researchers suspect that the PER protein inhibits its own production at night (by activating the brake protein HDAC1). However JARID1a reactivates CLOCK and BMAL1 by countering the influence of HDAC1 so that the synthesis of PER can start all over again.

In human and mouse cells that were genetically altered to under-produce JARID1a, the PER protein didn't reach its normal concentration each day. Treated with a drug that mimics JARID1a, the circadian rhythms of the mouse cells returned to normal.

Similarly genetically modified fruit flies displayed low levels of PER protein as well, so that their biological clocks got completely confused. By inserting JARID1a into the DNA of the flies, the HDAC brake got released, and the flies came back to a normal cycle.[11] -

In 2015 a study executed in the Department of Genetics of the University of Leicester[12] concentrated on examining the gene expression associated with early and late chronotypes in Drosophila melanogaster (the "common fruit fly"). The genetic system responsible for the circadian rhythm is rather similar between insects and human, therefore the scientists expect that some of the identified fly genes are also important for diurnal preference in humans.

The researchers compared the genetic material of different fly strains that either exhibited morning- or evening-like behavior. In the course of this they discovered nearly 80(!) genes influencing the time-dependent activity of the flies. Most of these genes are present in the mammalian genome as well, and therefore could be sensible starting points for research in human.

Dr Ezio Rosato, lead investigator, said: “A key finding of this study was that most of the genes that we identified are not core-clock genes, but genes involved in a diverse range of molecular pathways. This changes our view of the body clock, from a pacemaker that drives rhythms to a time reference system that interacts with the environment."[13]

- https://www.nasw.org/users/llamberg/larkowl.htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC544627/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suprachiasmatic_nucleus

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10381883

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12481141

- http://fusion.net/not-a-morning-person-blame-your-genes-scientists-say-1793847813

- https://biologydictionary.net/polygenic-traits/

- http://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822(12)00325-9

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12841365

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/8863

- http://www.salk.edu/news-release/alarm-clock-gene-explains-wake-up-function-of-biological-clock/

- http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fneur.2015.00100/full

- http://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/press/press-releases/2015/may/geneticists-clock-genetic-differences-between-larks-and-owls

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S105381191300921X

- http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-23988352

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21807927

- http://www.everydayhealth.com/columns/robert-rosenberg-sleep-answers/sleep-and-high-blood-pressure/

- http://www.cell.com/trends/neurosciences/abstract/S0166-2236(15)00174-5

- http://www.iflscience.com/health-and-medicine/should-work-start-10am/

- http://personal.lse.ac.uk/kanazawa/pdfs/paid2009.pdf

- http://www.sicotests.com/psyarticle.asp?id=331

Are "night owls" more susceptible to disease than other chronotypes?

The results of some studies indicate that "larks" tend to be more healthy in average than "night owls".

For example the method of Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) helped to find out that, compared to early and intermediate chronotypes, late chronotypes display white matter differences in the frontal and temporal lobes, cingulate gyrus and corpus callosum.[14] This could be the consequence of the fact that they often show a chronic form of jet lag together with sleep disturbances, susceptibility to depression and higher consumption of nicotine and alcohol.

Similar like the authors of the study I assume that "night owls" are not more fragile in health by definition, but as a consequence of the common social rhythms that clearly favor "early birds" and intermediate chronotypes. They conclude: "This study has far-reaching implications for health and the economy. Ideally, work schedules should fit in with chronotype-specificity whenever possible."

Here I see an analogy to the widespread belief that left-handers on principle would die more early than right-handers. That is not true in general, but happens under some circumstances when they are put into environments which suits better to right-handers, for example when they have to work on machines designed for "righty" operators or if in school they are forced to use their weaker right hand for writing.[15]

Lack of sleep is considered to increase the risk of many diseases, for example type 2 diabetes [16], high blood pressure [17] and a weaker immune system.[18]

Circadian rhythms differ not only between different individuals, but also alter during the lives of single persons. Whereas older people often become "larkish", especially teenagers and young adults tend to be late chronotypes. Sleep expert Paul Kelly suggests 11 a.m. as an optimal school start time for 18-year-olds.[19]

"Night owls" are more intelligent. :-)

Not to leave my fellow "night owls" too depressed by the insight that our modern world was designed by "early birds" for "early birds", I will end this article with something you may appreciate to hear. :)

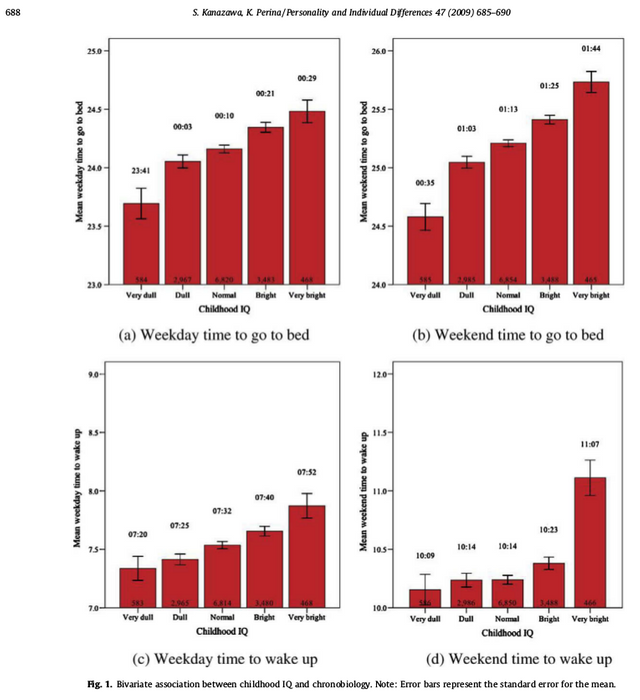

In 2009 Satoshi Kanazawa (who likes bitcoin will like this name as well, I guess) and Kaja Perina published a study in which they attest "night owls" to be more intelligent than average.[20]

In the abstract they state that according to their Savanna–IQ interaction hypothesis more intelligent individuals tend to acquire and endorse evolutionarily new values and behavior. Hereby they chose their values and preferences within a frame of given genetic predispositions. This extends to their circadian rhythms, too. Thus the Hypothesis predicts that intelligent individuals would rather tend to be nocturnal than less intelligent ones.

It has to be said that the mentioned Savanna–IQ interaction hypothesis[21] isn't uncontroversial, but nevertheless an appraisal of a big representative sample of young Americans confirmed the prediction that nocturnal individuals should be more intelligent than the "early birds" in average.

The graphics below stem from the study above and are rather self-explaining: more intelligent individuals (with a higher IQ) go to bed and also wake up later, especially at weekends when there is no external constraint to get up early. According to that research extreme "night owls" are also peculiar intelligent.