My day job includes studying plankton to understand and develop mathematical models of their growth and interactions (ecology). My capable technical staff person and I produced the following video earlier this year. The narration is in Japanese, because we work for an institute in Japan, but we recently added English subtitles:

Plankton are small, but far from simple

I once made the mistake of referring to plankton as “relatively simple organisms” during a discussion with one of my close colleagues, Kai Wirtz, while visiting him in Germany. He quickly corrected me and pointed out that they have been here a lot longer than we humans have. They’ve been here a lot longer than any mammals, in fact. That means that even though they are small, and lack brains, they have in their DNA the ability to survive a wide variety of changes in environmental conditions. They must, because they have made it through many ice ages, and likely through worse than that before there were any ice ages. Furthermore, plankton are considered ideal subjects for ecological studies because of their small size, large numbers, fast growth, and in some cases the ease with which they can be cultured.

Here I’ll introduce some of what I’ve learned about how plankton, and especially phytoplankton (free floating algae) dynamically adjust their physiology in response to ever-changing environmental conditions. You can see more, including the two previous videos in our series (so far without English subtitles, though) at my webpage.

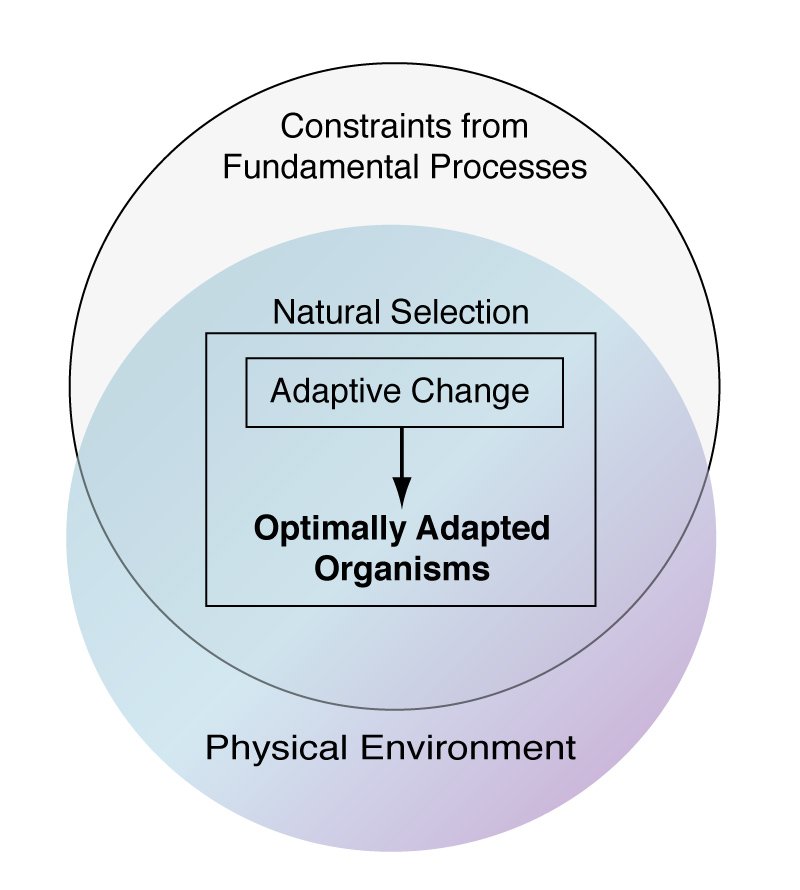

Optimization through natural selection

To understand and develop mathematical models of plankton, my colleagues and I find it quite useful to consider that natural selection should tend to lead to the evolution of organisms optimally adapted to their environments. This optimization happens subject to constraints imposed by both the physical environment and fundamental physics, chemistry, etc.

You can find more details in this review paper, Optimality-based modeling of planktonic organisms that I published in 2011, and in this 2014 perspective paper, Leaving misleading legacies behind in plankton ecosystem modelling.

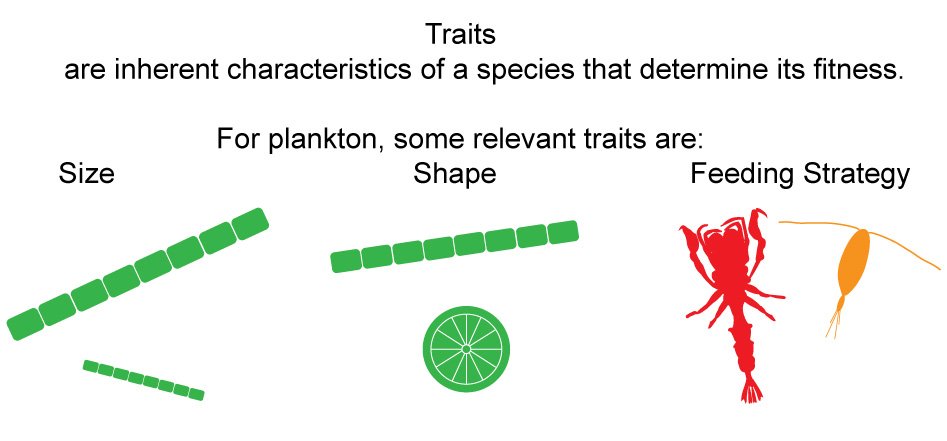

First, just to get some terminology out of the way, ecologists often refer to the defining characteristics of species as traits:

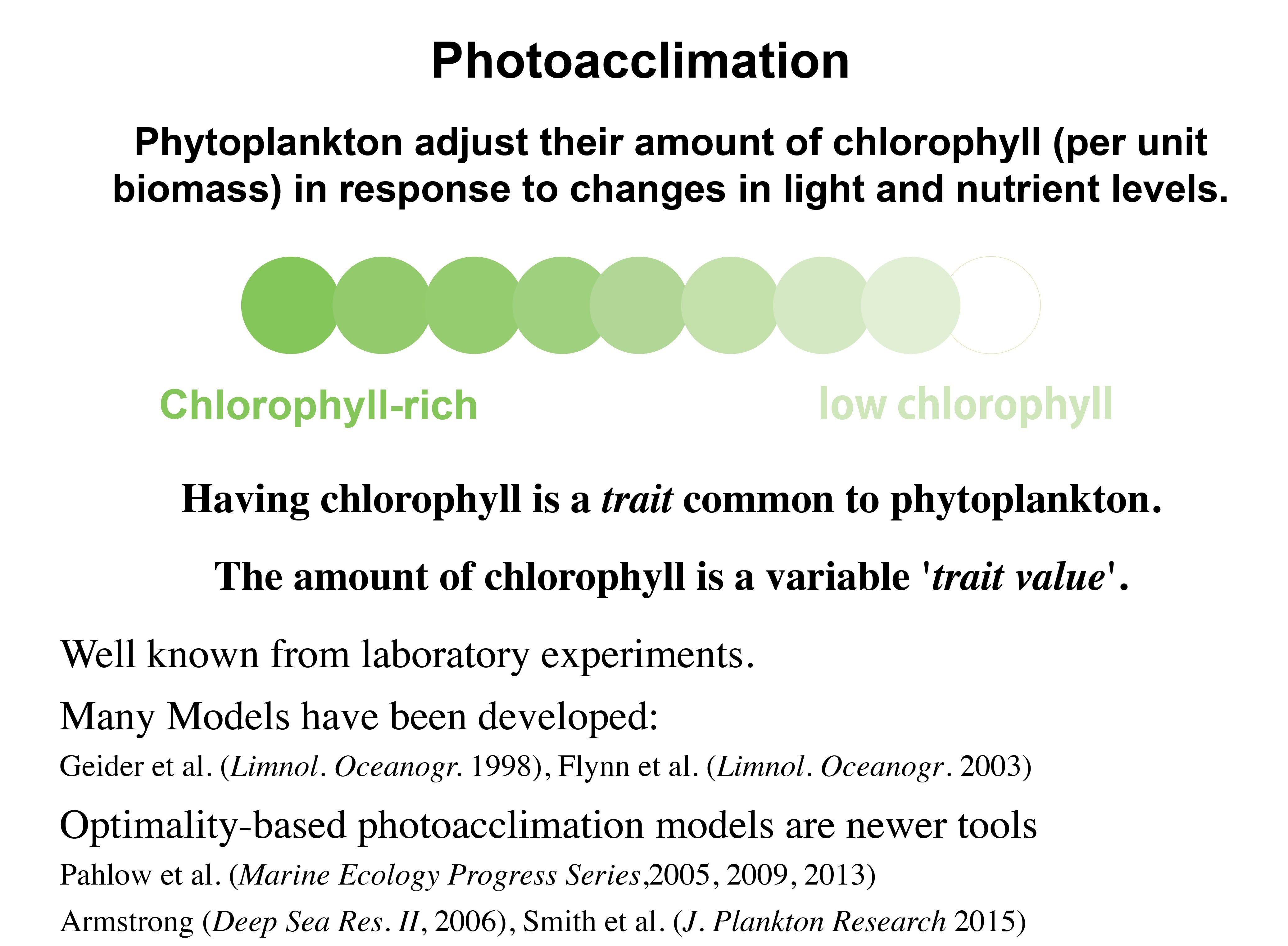

Organisms adjust their physiologies in order to change their trait values, both as they mature and in order to cope with ever-changing environmental conditions. Phytoplankton, which grow and produce organic matter by photosynthesis, are very good at adjusting their physiology to maximize their light-harvesting, and hence their growth rates. Photoacclimation refers to the reversible adjustment (acclimation) of chlorophyll levels within phytoplankton cells, in response to changes in nutrient and light levels:

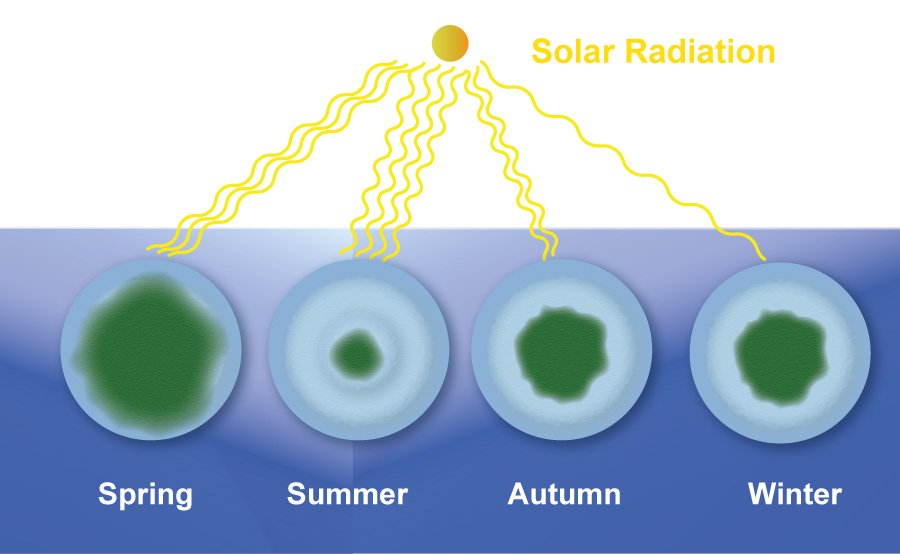

This results in typical seasonal changes in the chlorophyll content of phytoplankton living near the surface of the ocean:

The video above shows maps of the North Pacific with the seasonal change of chlorophyll as observed by satellite. Three factors cause those observed changes: 1) photoacclimation of individual cells as I just described, and 2) shifts in the dominant species with time and location, and changes in the total biomass of phytoplankton.

In future posts, I plan to explore the links between the ideas of ecology and those of economics and even human nutrition, as I began to do in this post.

S. Lan Smith

Kamakura, Japan

August 27, 2016