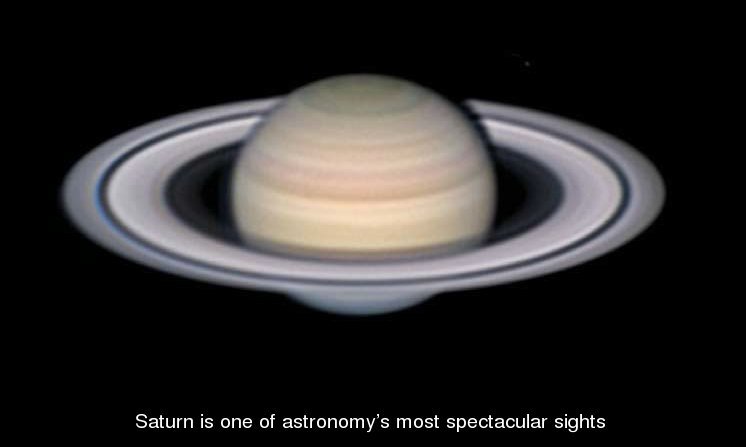

Perhaps you have noticed the difference. We’ve all shown Saturn to someone, or perhaps you’ve shared a clear view of a bright star cluster with someone who hasn’t seen such a thing before. In these and similar cases, the sheer beauty of the object is the whole point; any impressive facts are secondary. It doesn’t really matter how big or far away it is. When someone sees Saturn for the first time we hear a shout of surprise, a shared experience of joy at seeing something wonderful.

Now think about one of those other sights — the ones that make your gut tighten up, that stop your mind for a few seconds until you recover and are able to take it all in. You probably know the essential facts about this object, but it still baffles you. Chances are that you’re looking at something faint, perhaps a very distant galaxy cluster, or perhaps you targeted a quasar. But in each case you’re seeing something that is best appreciated when you know how unimaginably far away or immense it actually is.

You are probably not going to call a stranger over to see this. What you know you’re seeing overwhelms you, sets you back on your heels, but you don’t know if the person next to you can appreciate that gray spot in the same heart-stopping way that you do. It’s not because the image in your eyepiece is indistinct or faint, it’s because you’ve encountered the sublime.

The difference between these two kinds of experiences is not unique to astronomy. In fact, philosophers no less distinguished than Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant have pondered the different emotional experiences. They and other intellectual luminaries explored what affects us so deeply when we encounter enormous or uncountable things. They came to different conclusions but agreed that the sublime is distinct from mere beauty. So what really happens to us when we encounter something awesome in the eyepiece, and why does it feel so different?

Kant decided that beauty is social, that it can be reasonably summed up as something we share with others. But that is not so with the sublime. The experience of the sublime puts you right up against what you’re viewing; it’s just you and the universe and at first it seems like there’s a bad fit between the two. It’s a solitary experience. Kant explained it like this: faced with something that is just too much for us, we are halted in our tracks, unable to imagine or absorb it. But after this initial moment of blockage, our sense of reason comes to the rescue, and we’re able to fashion a kind of accommodation between ourselves and whatever is out there.

It’s that brief moment of being blocked, and then rescued, that produces the exhilaration of the sublime. What for a moment had seemed an imaginative defeat has become just the opposite, an experience of awe and of participation in wonder. It’s what you sometimes feel on the observing field on a good night. You can share the view, but your feelings can only be shared with the universe.