In the mid 1600s, the prominent English doctor Thomas Sydenham publicly claimed that foul vapors rose from the Earth's rotting center and infected cities, which led to epidemics. Another Englishman, Edwin Chadwick, put it even more bluntly when he said that "All smell is disease."

From ancient times until the 1880s, the miasma theory of disease was the dominant theory of disease in Europe and East Asia. Put simply, it claimed that bad odors and foul vapors caused disease. Miasma comes from ancient Greek and translates to "pollution". It was an incredibly dominant theory for that entire period. Though we now know that this is a misconception, and that disease in fact comes from microscopic invasive organisms, for most of history there were actually quite convincing reasons to believe in the miasma theory of disease.

An 1800s representation of miasmas causing cholera.

Image in the public domain.

The prevalence of miasmic theory permeated science, culture and literature. Malaria literally means "bad air". In Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre, a typhus epidemic kills a number of girls in the orphanage the titular character resides in, and is quite explicitly caused by the orphanage being in a "cradle of fog and fog bred pestilence". Napoleon's doctors' support of the miasma theory of disease likely contributed to the severity of the typhus epidemic that ravaged his Grande Armée during his invasion of Russia, which was the beginning of the end for Napoleon.

That's not to say that adherence to the miasma theory of disease was universal. There were several other theories as well, but only one of them was a real competitor to the miasma theory of disease- the contagion theory, the idea that there was some sort of agent being transmitted between individuals causing the disease. To be clear, however, it might have been a competitor, but it was still a distant second- in the English debates regarding the transmission of cholera in the 1840s, less than 5% supported the idea that cholera was primarily transmitted contagiously. So how could so many doctors and scientists be so wrong?

Cholera bacteria.

Fair use image

In order to understand exactly why they came to the wrong conlcusion, we have to put ourselves in their shoes. First off, they didn't have microscopes. They had absolutely no way to see invasive microorganisms, so they had to take it on faith that these invisible monsters actually existed. And for all that we as a society tend to imagine people before our time as fools for not knowing everything we do, these were, for the most part, pretty intelligent and capable men who would have done very well for themselves if they'd been born in our time. In fact, much of the scientific data at the time tended to lean towards their perspective- creating plans to treat epidemics and diseases as though they were caused miasmically often DID work. Removing garbage and human waste from the streets did, in fact, reduce disease rates, albeit not for the reasons they thought. In addition, wealthier, better smelling neighborhoods tended to have less disease than poorer, smellier neighborhoods. The miasmic theory of disease also tended to claim that cities and development should avoid swampy lowlands- areas which do, in fact, often harbor diseases that can erupt into epidemics.

This doesn't even touch on the problems that faced the contagion theory of disease from the contagions themselves. While some diseases spread directly from person to person, like the common cold, smallpox, or polio, many others spread in other ways. Cholera spreads from infected fecal matter into the water supply and back into people. Malaria is a protozoan that is spread by mosquitoes, and then repeatedly relapses as reservoirs of the disease in your liver reactivate. The bubonic plague and many other diseases are zootics- they spread from animals to people. Many of these methods of spreading far more closely resembled the data that would be expected from the miasmic theory of disease than they did the contagion theory of disease to scientists and doctors at the time, and for good reason.

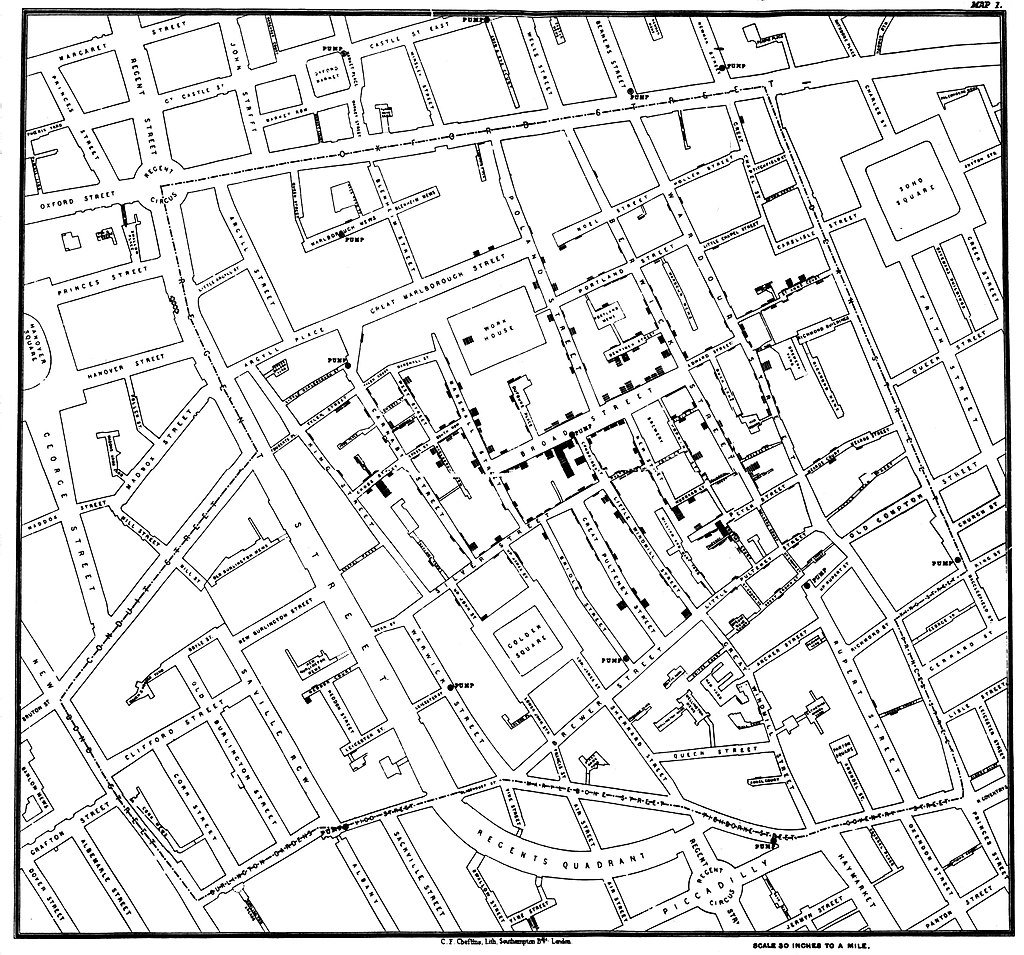

The tide did slowly begin to turn, though. One of the most significant moments was the 1854 cholera outbreak in London. A prominent doctor and skeptic of miasmic theory at the time, John Snow (no relation to the Game of Thrones character, though I do like to imagine that the character is named after the doctor) managed to map the outbreak and successfully prove that it originated from a single water pump, the Broad Street Pump, and successfully head off the epidemic.

John Snow's map of the outbreak. The black bars on the buildings represent the severity of the outbreak in the examined buildings, and the infected pump can be seen on Broad Street. Image is in the public domain.

Following John Snow's triumph, the spread of the microscope, the accomplishments of Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch's postulates, and the work of many other scientists contributed to the eventual rise of the germ theory of disease, which has saved countless lives to this very day. The germ theory of disease is one of the greatest accomplishments of science, without a doubt, and its rise is a fascinating and rich epic that I've barely touched on.

This whole epic touches on something else as well, though- the way in which science itself develops. Thomas Kuhn, in his philosophy of science work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, described a pattern in the way that new scientific theories arise. Rather than science being the slow accumulation of data, as it was commonly described before Kuhn, Kuhn claimed that science operated under paradigms that are periodically overthrown. The usurpation of miasmic theory's throne by the germ theory of disease is one of the most clear-cut examples of Kuhn's ideas.

While miasmic theory is a major misconception by today's standards, by the standards of the time, it was actually pretty decent science. In its better forms, it did actually save a lot of lives by ensuring streets clean of human waste and garbage, and avoiding swampy lowlands, among other prescriptions. It can really only be understood as harmful in comparison with the early germ theory of disease- and again, only by today's standards. By standards at the time, there was simply not yet enough evidence to conclusively prove miasmic theory wrong. As that evidence accumulated, science responded, and overthrew the miasmic theory. Science is sometimes slow to change course, but when it does so, it has very seldom been wrong to do so. This is one of its greatest strengths.

.......................................................................................

This post is an entry in @Suesa's Science Challege #2.

All photos in this article are public domain or fair use images found used from the Wikimedia Foundation.

Bibliography:

-The Ghost Map, by Steven Johnson

-The Illustrious Dead, by Stephan Talty

-The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn

-https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germ_theory_of_disease#cite_ref-21