In the Clarendon lab in Oxford, where physicists keep a battery with the longest battery life the world has ever seen. It powers the Oxford Electric Bell, and it’s been running almost continuously for over 176 years.

It was bought by the Reverend Robert Walker, who was a reader in experimental philosophy at Oxford. That’s what they used to call physicists in those days, and should hopefully give you an idea of quite how long ago we’re talking.

He brought it back in 1840. So let’s just take a second to put that in some context. If we skip back another 60 years, the year is 1780. Mad King George is still on the British throne, the US declared independence just four years earlier, and Napoleon is still a schoolboy. Over in Italy, a physicist, Luigi Galvani, was dissecting a frog’s leg with metal tools, but when he touched the nerve, he saw the frog’s muscles twitch and he thought that this was “animal electricity”.

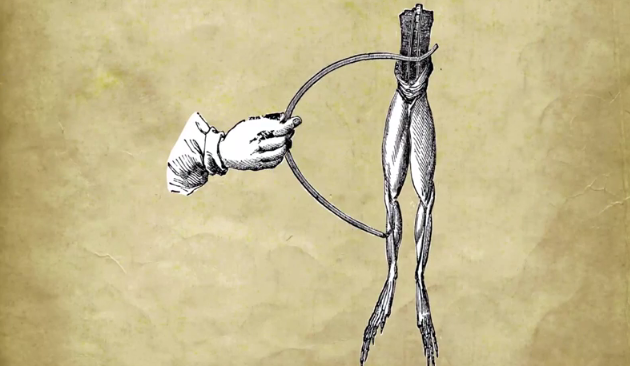

Another Italian physicist, Alessandro Volta, heard of this experiment, and realized that the frog’s leg was just a fancy electrolyte that allowed current to flow between the copper and iron tools that Galvani was using. And Volta went on to invent the first ever battery in 1800, called the voltaic pile, made by piling up discs of copper and zinc — well, here I’ve got aluminum foil as in the picture — and sandwiching them with discs of cardboard that was soaked in brine.

And by piling up cells like, you can see that you produce a battery, and it still works!

And then in 1825, the London instrument makers Watkin and Hill made the Oxford Electric Bell and the dry pile battery that powers it.

And although it was just 25 years after Volta invented the first ever battery, this battery here went on to outlive every single other battery the world has ever produced and has won the Guinness World Record for the world’s most durable battery.

How does such an old battery last so long? Well, it’s a dry pile battery, so it’s got a paste inside with the minimum amount of water needed for the electrolyte to work. And all that water is kept in with this solid sulfur coating.

But beyond that, we don’t really know what’s inside it. Looking at diagrams of other batteries from around the time, it’s probably got about 2000 of discs made from zinc and manganese dioxide all stacked up.

But to find out what it’s exactly made of, we’d have to cut it open and end its 176-year run. In this time, the bells have run around 10 billion times, give or take, although this is an active physics laboratory, so thankfully for all the physicists around here it’s now inaudible and it’s behind two panes of glass. Each time the bell rings, the clapper takes a tiny one nano-amp of current, but the voltage between the bells is a whopping 2 kilo-volts. That’s nearly 10 times the voltage of UK mains electricity.

How long can it keep on running for? Well, no one really knows. The people round here reckon that the bell will break from wear and tear long before the battery runs out of power.

In 1841, just one year after Oxford bought the bell, the instrument makers themselves wrote in a letter, “The residual electrical power sufficient to keep up the ringing of the bells “seldom lasts more than three or four years. “It’s a pretty apparatus, but alas, “very transient in its working powers.” How wrong could they be?