I’ve spent a significant part of my life studying things that other astronomers studied before me. Many asked me why do I put so much time in studying something that has already been discovered and meticulously described? Let me tell you a story from my childhood. A short time after Apollo 11 landed on the surface of the Moon, I was looking at the lunar disk through my 60-mm refractor. My dad was curious to why I still look at an object that has been just observed by Armstrong and co. I’ve seen pictures and I’ve read about the landing. What was so interesting in the Moon? I don’t remember my own answer. I hope that it was similar to what I would have answered today.

A plethora of stars and constellations have been described and catalogued. Some of them found their places in catalogues when first telescopes were advanced pieces of technology. Since those dark times, we have expanded our knowledge beyond the bravest expectations of first telescope users. Some would question the very idea of studying and observing some objects once again. Some would argue that it’s similar to re-inventing a bicycle. Why bother looking at the night sky through simple telescopes that don’t even allow you to contribute to science?

There are some amateurs that still can contribute and their small projects and simple equipment still deliver interesting discoveries like Epsilon Aurigae that was widely covered in media. We call this “meaningful observations”. However, the vast majority of “casual” sky-watchers will never add any value to the cumulative knowledge about the world around. So why bother?

Image Credit: Pyramidg.org

The answer is that everything has a meaning. My observations do not have to lead to ground-breaking discoveries. The very contribution is far from being my intent. My telescope opens up a whole new world to me and observing it is a satisfying experience on its own. Take Giza Pyramids for example. You can read about them in a bunch of history books, but does it make you less interested in visiting Giza in person?

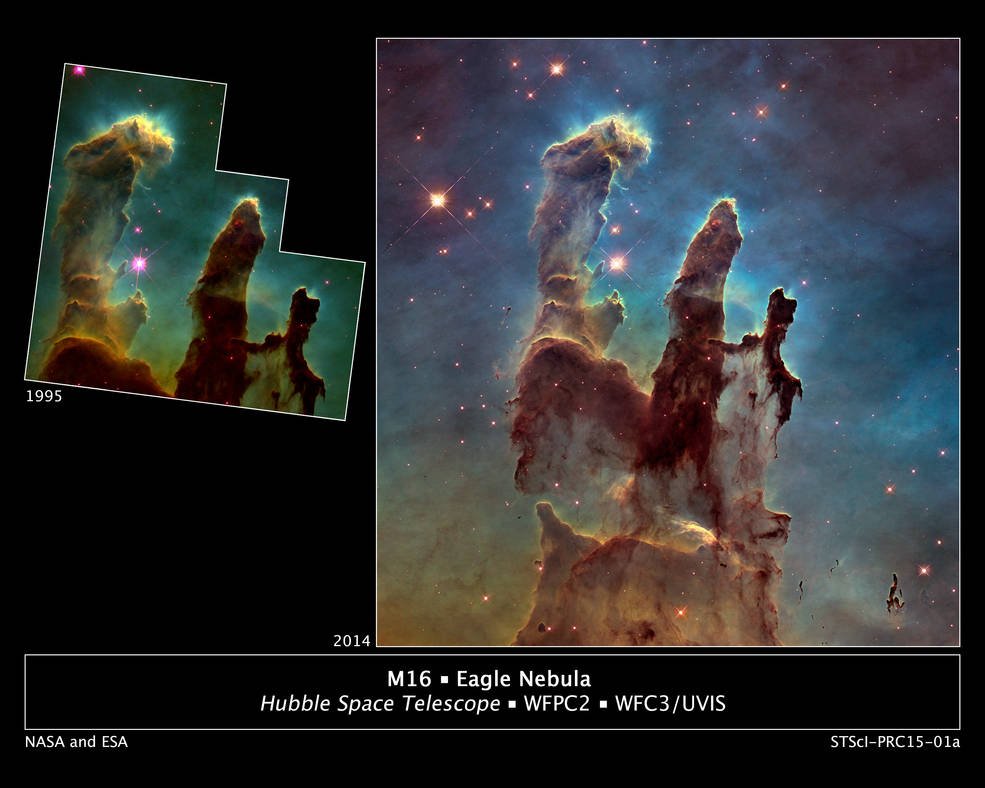

Observing the Eagle Nebula (M16) is the same experience. Just like the Orion Nebula (M42), the Eagle Nebula has been studied for a long time and the amount of knowledge related to this nebula is enough to make sure that amateur astronomers will unlikely discover anything significant. However, the very fact that other people have seen it doesn’t make it less attractive. A small illustration of pyramids in a history book will never give you a feeling of connection to ancient times when you touch the stones of a pyramid.

Eagle Nebula (M16), NASA/ESA/Hubble

One needs to touch and experience in order to understand and feel satisfied. That’s what I felt when studying the Moon after Apollo 11. That’s what I feel today when looking at the sky. No imagery can give me the same kind of feeling. The surface of the Moon and amazing shine of star clusters lose their charm when portrayed in magazines and scientific TV-shows. The universe talks to you when you look at it and this reason alone is enough to make every minute of my life spent looking through my telescope meaningful.