Depending on how much contact you have with me on steem.chat or discord, you know or don’t know that I’m currently working on my bachelor thesis. This caused my posting behavior to go from “once a day” to … well, “once every one or two weeks, maybe.”. A bit over a month and things should be back to normal, although I assume it’ll be hard to go back to the regular posting I did almost a year ago (my Steem birthday is 16th of June!).

Nevertheless, I want to provide you with some scientific content again. While writing the introduction to my thesis, I had to do some research on nucleases. After finishing that, I looked at all the sources cited and thought to myself ”Hey, I already put so much work into this, I could just as well use it to get some easy money on Steemit teach people something!”.

So, today, I’ll present to you a post about nucleases, the things that are used to edit genomes.

If you don’t know what DNA is made of, can’t tell the difference between amino acids and nucleobases, and think guanine is a fruit, please read my post on the building blocks of life for a fun introduction to … uhm, the building blocks of life. You’ll need it. I mean, you can read this post without having understood any of the things mentioned. I will include silly sketches. Maybe those help.

What’s a Nuclease?

After you’ve read the introduction to “the building blocks of life”, you now know that nucleobases are the things DNA consists of. The word nuclease consists of two parts: Nucle- and -ase. The nucle- refers to the nucleobases, the -ase is a word ending usually used for enzymes. Most of you probably think that enzymes only break stuff down (that’s what you’re usually taught), but in general, enzymes catalyze biochemical reactions that would take millions of years if left to their own. Pretty neat, right? @suesa

Nucleases specifically are enzymes that make changes to DNA or RNA, which both are made up of nucleobases.

Which explains why nucleases are used for genome editing! If you want to make changes to a genome, you use enzymes that catalyze such a reaction. But what does actually happen?

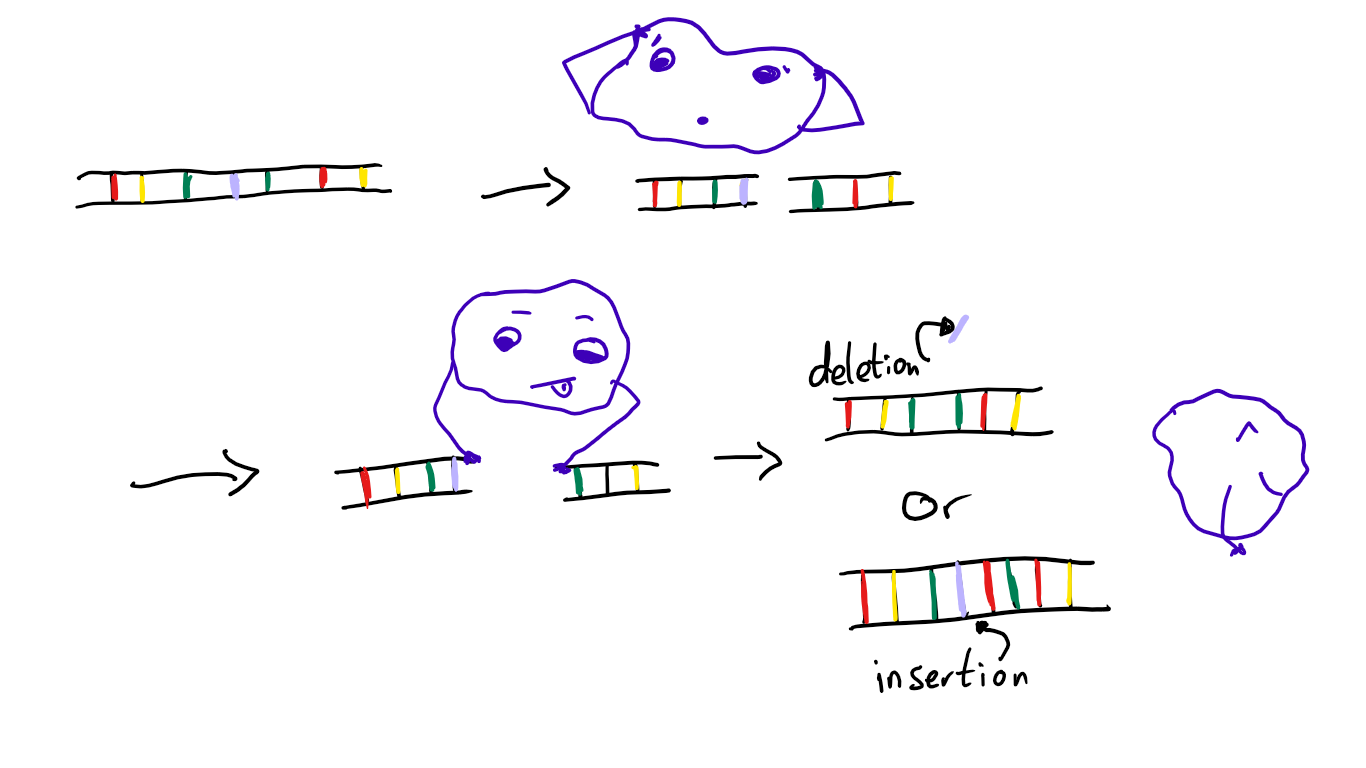

The general way nucleases used in genome editing work is that they introduce a break to the DNA double-strand. This break is then repaired through one of two pathways: Nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ, I am not going to write this out every time) or homology-directed repair (HDR, not going to write this again either)1. What’s that? Well, it’s in the name!

NHEJ does not require a sequence homologous to the DNA that has been broken in two. Instead, enzymes simply “glue” the ends together in the best way they can. This can lead to random insertions or deletions (so-called “indels”, not to be confused with “incels”) of nucleobases.

Cool way to deactivate a gene by causing a random mutation. Not so cool if you want to insert something specific. That’s where HDR comes in.

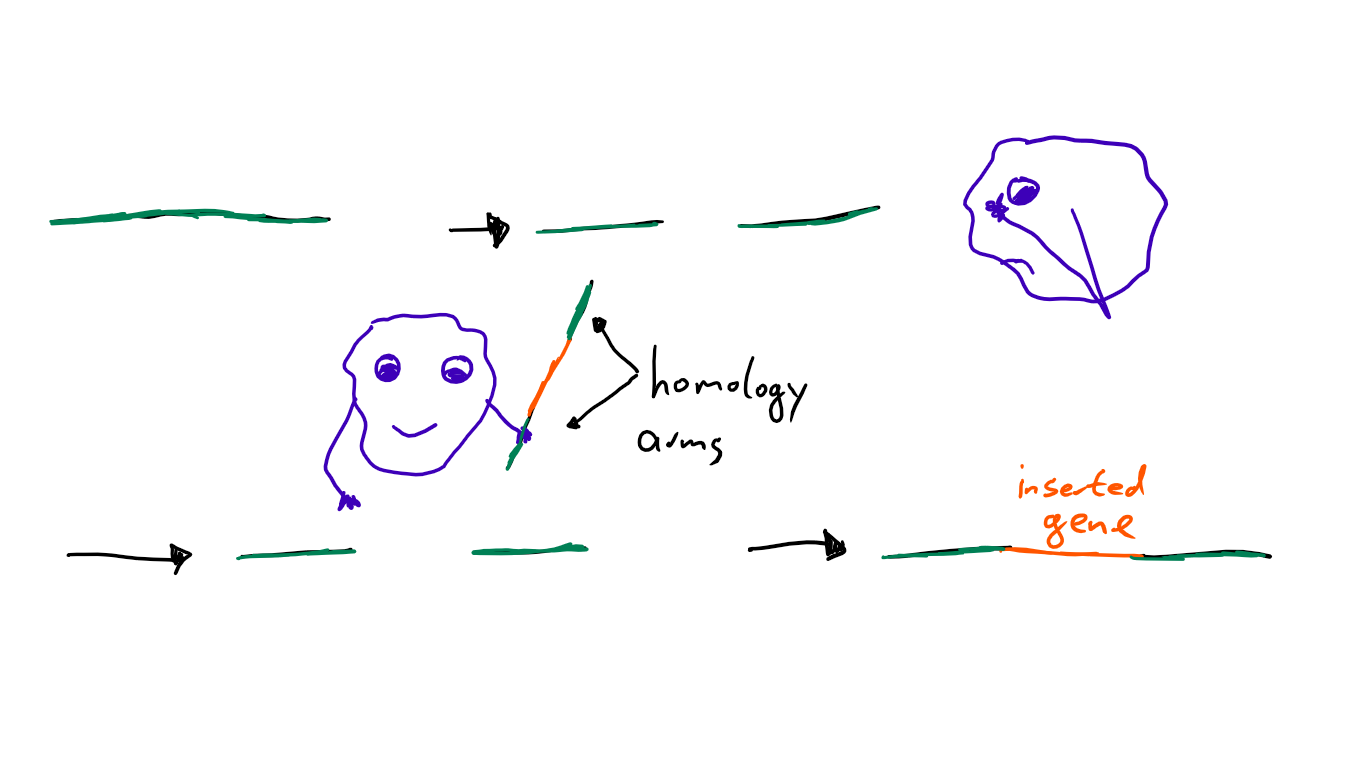

HDR is a repair of DNA directed by homology, which means the enzymes that repair the DNA have a template they use. A blueprint for what they want to achieve. In a natural context, HDR uses the second copy of the gene that’s available in the cell. But if we want to introduce a DNA sequence artificially, we need to provide that template ourselves. This template needs two “homology arms” (= sequences that are the same as the DNA sequence where the break happened) and between those, the insert (= piece of DNA we want to introduce). Then some biochemical magic process happens, and we got our mutation! Easy as that.2

ZFNs and TALENs

Biologists love their abbreviations. Then again, who wants to write a text about zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector-based nucleases (TALENs) and write out the full name every damn time? Not me. Certainly not most of the others. So we make it easy and use an abbreviation. But what’s behind those? And why do I group two nucleases, that sound completely different, together? Am I that lazy?

Yes, but that’s not the reason I’m putting those two in the same section. ZFNs came first. They were discovered in the egg cells of a specific frog (Xenopus laevis, for those interested)3. What do they do?

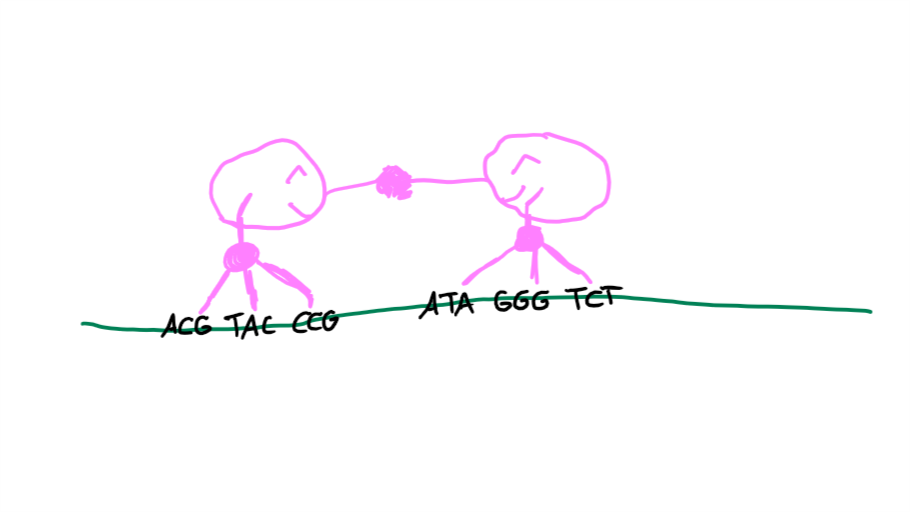

ZFNs have, as the name suggests, zinc fingers. Those have a specific nucleobase triplet they target. 3-5 fingers per ZFN result in a pretty good recognition of a target sequence where the DNA should be broken in two. Even better, you need two ZFNs, which each has their set of “fingers”, to create this break.4 You can imagine it like this:

The two ZFNs find the DNA sequence, they dimerize (“two get together and connect”), they break the DNA, the DNA is repaired through either NHEJ or HDR, everyone is happy.

What about TALENs?

Basically, the same concept.

TALEs (transcription activator-like effectors, basically what I wrote earlier just without the “nuclease” part) are proteins from a certain kind of bacteria that infects plants5. Those alone can not break DNA. But they can find and bind to DNA sequences! And that very efficiently6!

Biologists don’t like to see good systems go to waste. And they already knew how ZFNs work. What they then did was taking a ZFN and replacing its zinc fingers with the system TALEs use for DNA recognition7. Who would have thought that real-life Frankenstein would be so … boring.

That’s the only difference between ZFNs and TALENs. That’s why I grouped them together. Understand one, understand the other! If it was just always this easy.

CRISPR/Cas9

CRISPR/Cas9 is the newest system using a nuclease to induce DNA breaks, and …

Oh, look at the time! I think CRISPR/Cas9 has to wait a bit more; this post is already very long.

Stay tuned!

Sources:

1Gaj, T., Gersbach, C. A., & Barbas III, C. F. (2013). ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Cell Press, 31(7), 397-405. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004

2 Resnick, M. A. (1976). The repair of double-strand breaks in DNA: A model involving recombination. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 59(1), 97-106. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(76)80025-2

3 Miller, J., McLachlan, A. D., & Klug, A. (1985). Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. The EMBO Journal, 4(6), 1609–1614.

4 Carroll, D. (2008). Zinc-finger Nucleases as Gene Therapy Agents. Gene Therapy, 15(22), 1463–1468. doi:10.1038/gt.2008.145

5 Bogdanove, A. J., Schornack, S., & Lahaye, T. (2010). TAL effectors: finding plant genes for disease and defense. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 13(4), 394-401. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.010

6 Schornack, S., Meyer, A., Römer, P., Jordan, T., & Lahaye, T. (2006). Gene-for-gene-mediated recognition of nuclear-targeted AvrBs3-like bacterial effector proteins. Journal of Plant Physiology, 163(3), 256-272. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2005.12.001

7 Christian, M., et al. (2010). Targeting DNA Double-Strand Breaks with TAL Effector Nucleases. Genetics, 186(2), 757-761. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.120717