This post was inspired by the Himal-Health-Contest #3 which asked participants to write a response concerning cancer. I don’t have a lot of direct experience with this disease so I can’t write a heartfelt story about how it has affected my life. However, I have been a research scientist for over 10 years so I thought I would delve into an inserting aspect of cancer research. Since my specialty is microbiology, I decided to look at the connection between cancer and the microbiome.

What is the microbiome?

The human microbiome is the collection of microbial organisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses etc.) that live in and around our bodies. It consists of trillions of microorganisms — outnumbering human cells by 10 to 1. However, microbial cells are much smaller than human cells so it only comprises ~2% of a human’s body weight (1). The majority of the microbiome is located in the gut, but components of the microbiome can be found on almost every part of the body.

Although the microbiome is non-human, it is a distinct organ that carries out activities essential to our well-being. Components of the microbiome have been shown to protect against pathogens, aid in digestion, reduce cardiovascular disease, and improve overall health (2). These microbes are considered symbiotes: We provide shelter and nutrients for them and they help us in turn.

The microbiome helps prevent cancer

Many studies have shown that the microbiome plays an active role in preventing and treating cancer. The microbiome protects the body against cancer-causing pathogens like Helicobacter pylori (3). It has also been shown that commensal bacteria can help activate the immune system against cancerous cells and regulate inflammation. The inflammation response is an important factor here because it may increase the risk of cancer* (see @justtryme90’s fantastic article on cancer and inflammation for more info on this subject). In addition to these general effects, there are numerous studies showing that the microbiomes of patients with cancer often deviate from that of healthy humans (4). Understanding why this happens may provide key insights for certain cancers.

Leveraging the microbiome against cancer

To illustrate the kind of work being done in this field, I’d like to highlight some research that shows the potential use of the microbiome in helping detect cancer. As I mentioned previously, patients with cancer often have unusual microbiomes. Several scientists have seized upon this observation as a potential way to detect cancer. The research article “Stool Microbiome and Metabolome Differences between Colorectal Cancer Patients and Healthy Adults” by Tiffany Weir et al. from the Ryan lab at the University of Colorado aims to do just this (5).

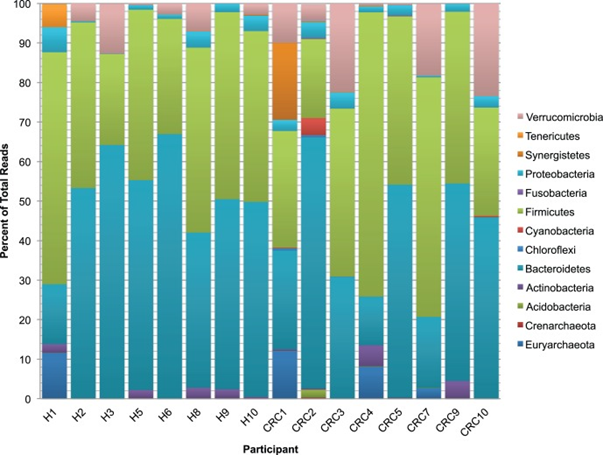

In this article, researchers compared the gut microbiomes of healthy adults and adults with colorectal cancer. They were able to determine the gut microbiomes of humans by analyzing the bacteria excreted in their stool. In other words, they collected poop from all their test subjects. Now poop is always humorous, but it’s also quite convenient in this context as gathering it is non-invasive and humans are always producing it. Once the researchers had analyzed all this crap (ha!), they compiled their findings in the chart below.

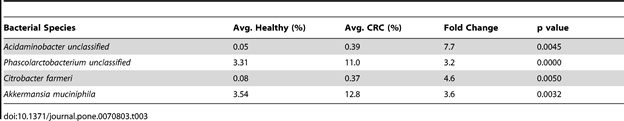

This chart shows the relative proportions of different types of bacteria in each subject with each column representing the microbiome of an individual and each color representing a specific phylum of bacteria. Now if this chart just looks like a bunch of gibberish, I don’t blame you. Microbiomes are insanely complicated and even though it’s clear that individuals have differences in their microbiomes, it is not at all clear which differences are important in regards to cancer and which are simply natural variation between different people. Fortunately, the researchers did a lot of work crunching the numbers from this data set and were able to find some clear differences between healthy patients and cancerous patients. Some of the most significant differences are shown the table below.

As you can see, several bacterial specific are significantly overrepresented in patients with colorectal cancer (abbreviated CRC in the chart). For example, akkermansis muchinphila composes only 3.54% of the gut microbiome in the healthy group, but nearly quadruples in prevalence to 12.8% in cancerous subjects.

I like this study because it directly shows a use of the microbiome in helping detect cancer. It’s easy to envision a cancer screen in the near future in which stool samples are analyzed for cancer-associated bacteria. However, it is important to point out the limitations of this study. We still don’t know why patients with colorectal cancer show increased levels of certain bacterial strains and we don’t know if these strains are in any way causing the cancer or are merely associated with it.

Anyways that’s all for today. Big thanks to @himal for inspiring this post and good luck to everyone else participating in the competition.

References:

(1) https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-human-microbiome-project-defines-normal-bacterial-makeup-body

(2) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4290017

(3) http://cancerpreventionresearch.aacrjournals.org/content/10/4/226.long

(4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4742587

(5) http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0070803