Image Source

This post was inspired by a conversation I had at genomics conference several years ago. During a poster session, I came across a metagenomic report on the changes in the bladder microbiome during an infection. While talking to the presenter, she casually pointed to a figure depicting the control microbiome of the bladder. In other words, it showed the bacteria that naturally live in the bladder. This immediately caught my attention because it challenged the long held notion that urine is sterile. I asked the presenter about it, and though she had fielded this question plenty of times before, she was excited to tell me that her lab was one of the first to show that the bladder and normal urine contain a significant number of microbes. In fact, her explanation as to why scientists used to believe urine is sterile and how they refuted that initial assumption was fascinating enough that I still remember it to this day.

To adequately explain this topic, I went to google scholar and dived into the literature on the subject. Initial papers on urine bacteria and the bladder microbiome started popping up around 2012. However, I decided to focus on an excellent review of the subject called “The Bladder Is Not Sterile: History and Current Discoveries on the Urinary Microbiome.” (1) This review was written by Krystal Thomas-White, Megan Brady, Alan J. Wolfe, and Elizabeth R. Mueller, and was published in the journal Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports.

Despite my misgivings about the journal, the review in question turned out to be extremely well-written and gave an excellent synopsis of this topic. More importantly, they made it all easy to understand. They began with an explanation as to why the “urine is sterile” myth arose in the first place.

Why does everyone think urine is sterile?

This myth primarily arose because urinary bacteria tend to grow very slowly. In the mid-1800s, scientists like Louis Pasteur and William Roberts showed that urine will become contaminated with bacteria and turn cloudy if exposed to air, but would remain clear if kept in a sealed tube (3).

How scientists disproved this myth.

The rise of metagenomics is responsible for dispelling this long held belief. Metagenomics is the study of genetic material from the environment. It is commonly used to identify uncultivatable bacteria from unusual samples. To identify bacteria in urine, scientists used a technique knowns as 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing.

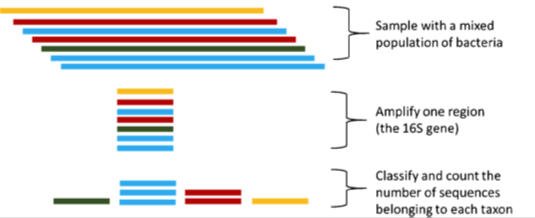

Overview of 16S rRNA sequencing (1)

This technique is summarized in the figure to the left, but in brief, a conserved gene found in all bacteria known as the 16S gene is amplified with PCR and sequenced using next generation sequencing technologies. Using this technique, scientists were able to identify bacterial strains within healthy urine samples.

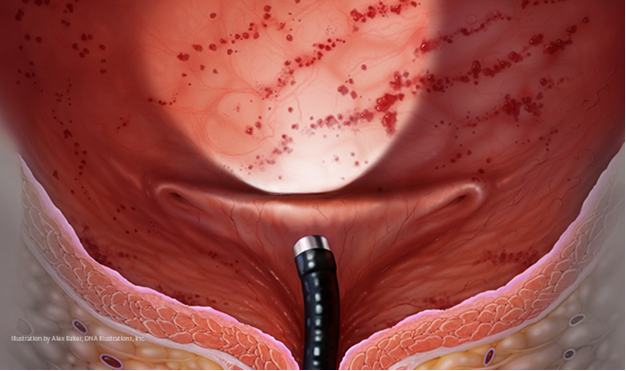

Although these results were promising, scientists still had to prove that these bacteria were not contaminants picked up during sample collection. The typical method for collecting urine was the standard “pee in a cup” technique. Though easy to perform, environmental bacteria could get in the cup or urine could pick up bacteria through, as the researcher put it, “vulvo-vaginal contamination” (contamination from the penis isn’t really discussed so I guess that’s one point in guy's favor for being the cleaner gender). Scientists needed a guaranteed method for extracting urine without any possibility of contamination so they turned to suprapubic aspiration. This is a fancy way of saying the injected a needle directly in the bladder to extract samples (6). It makes me cringe a bit, but I can’t argue with the results. Using suprapubic aspiraction, the scientists were able to show that uncontaminated urine contained bacteria in healthy individuals.

Despite these discoveries, the urinary metagenome may have remained a footnote of medical science were it not for the increased emphasis we now put on the human microbiome. Scientists now know that most of the human body is colonized with non-pathogenic bacteria. These bacteria are collectively known as the microbiome and play important roles in health and disease. Thus, the natural bladder microbiome could be a medically relevant component of a healthy bladder.

Medical relevance of the bladder microbiome

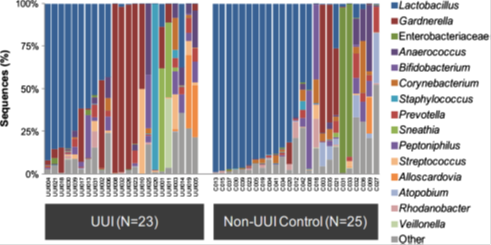

Besides dispelling a common myth, metagenomics finally gives us the tools needed to adequately study the bladder microbiome and, more importantly, urinary tract infections. Scientists can now examine patients with urinary tract infections and identify the specific bacteria causing the infection. Preliminary studies have already shown promise with clear differences between healthy bladders and infected bladders.

Relative abundance of different bacterial communities in patients with urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) compared to control patients (1).

In the future, doctors hope to be able to use metagenomics to identify pathogenic bacteria in the bladder before they become a massive infection. In fact, some studies have already yielded promising results (7). Metagenomics studies may also be able to identify probiotic bladder bacteria, microbes that promote bladder health and fight infection. However, only time will tell how much of an impact these metagenomics studies will have on our pee.

References

(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27182288

(2) .jpg)

(3) https://www.jstor.org/stable/25257957

(4) https://fankhauserblog.wordpress.com/1993/02/17/preparation-of-bacteriophage-stocks

(5) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20064694

(6) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suprapubic_aspiration

(7) https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/08/21/178178

About the Author: I’m a research currently living near Boston. I recently left academia to work in in industry, but I miss teaching so I decided to start writing articles on interesting discoveries in the world of microbiology. My goal is to uncover subjects that are unusual, unique, and might one day have a major impact on our daily lives. If you like this work, please consider giving me a follow: @tking77798

SteemSTEM

I’ve decided to start putting my support behind the @steemstem project and I encourage you to do the same. SteemSTEM is a community driven project which seeks to promote well written/informative Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics postings on Steemit. The project not only curates STEM posts on the platform through both voting and resteeming, but also re-distributes curation rewards as STEEM Power, to members of Steemit's growing scientific/tech community.

To learn more about the project please join us on steemit.chat (https://steemit.chat/channel/steemSTEM), we are always looking for people who want to help in our quest to increase the quality of STEM (and health) posts on our growing platform, and would love to hear from you!