One of the most outrageous, seemingly impossible things I could tell you that is nevertheless true is "The United States has had the technology needed for interstellar flight since the mid 1970s." That can't be true, surely? Why then aren't there starships on their way to exoplanets as we speak? As usual, the devil is in the details.

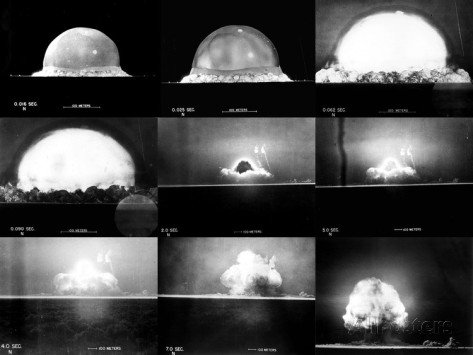

The devil, in this case, is the atomic bomb. Following the Trinity tests, it was noticed that one of the metal test objects was virtually unharmed in some places by the blast. After later study it was determined that this happened because the object happened to have graphite oil on those spots. The oil absorbed the intense heat of the nuclear conflagration, boiling away in the process but leaving the metal underneath wholly unblemished.

News that there existed a relatively simple way to insulate metals against even close range nuclear blasts electrified engineers of the day, including Freeman Dyson. George Dyson, Freeman's son, gave an excellent TED talk about his father's involvement in the Orion project and the astonishing feats of manned spaceflight it could have made possible by now.

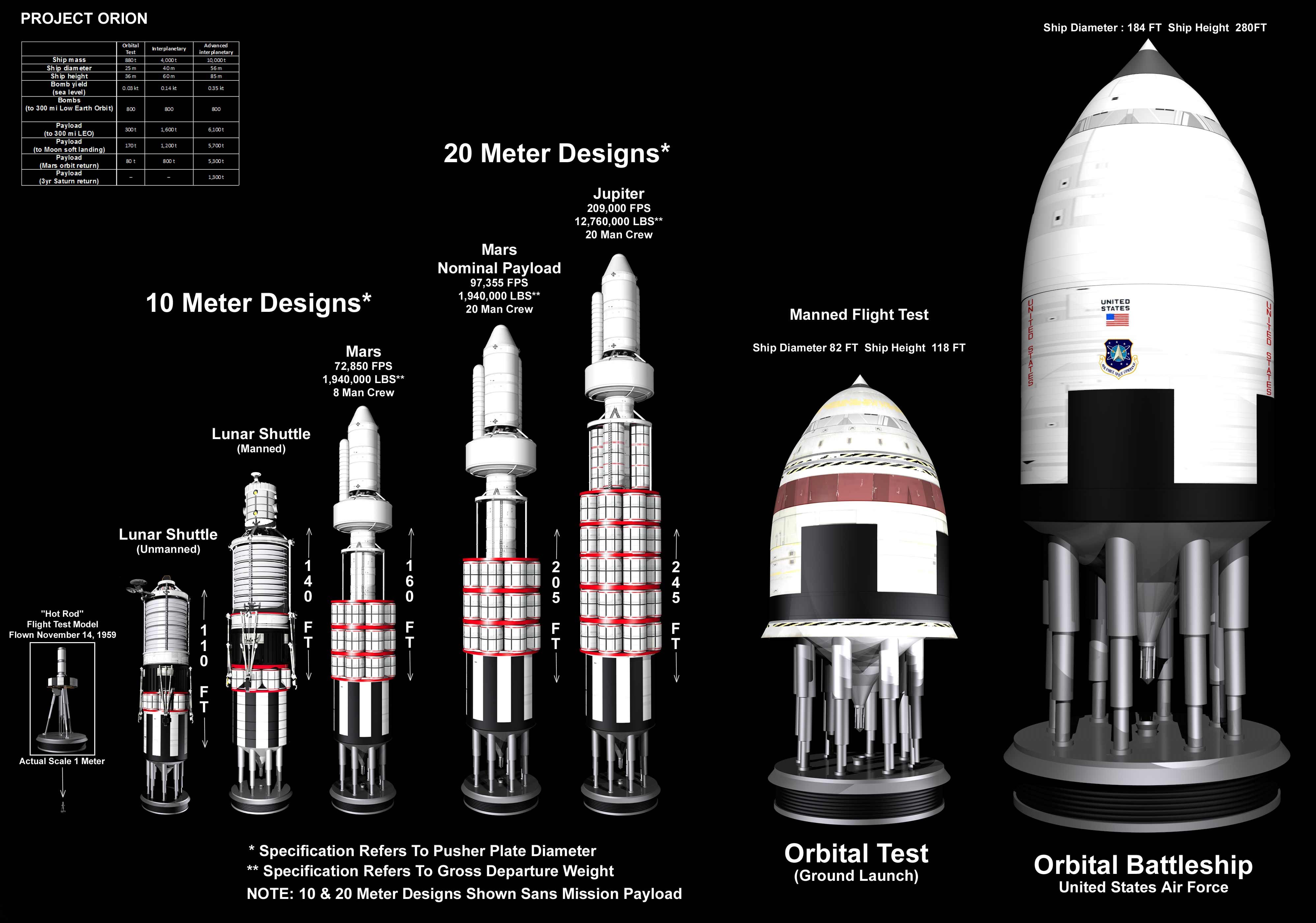

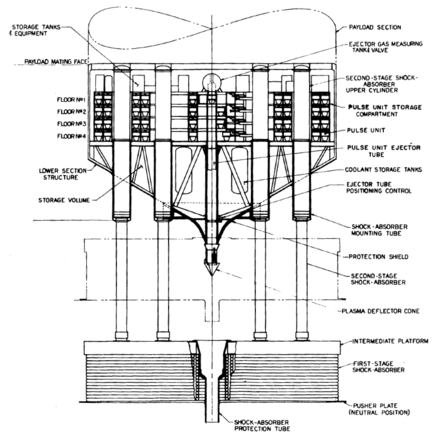

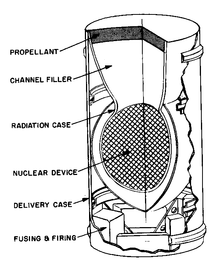

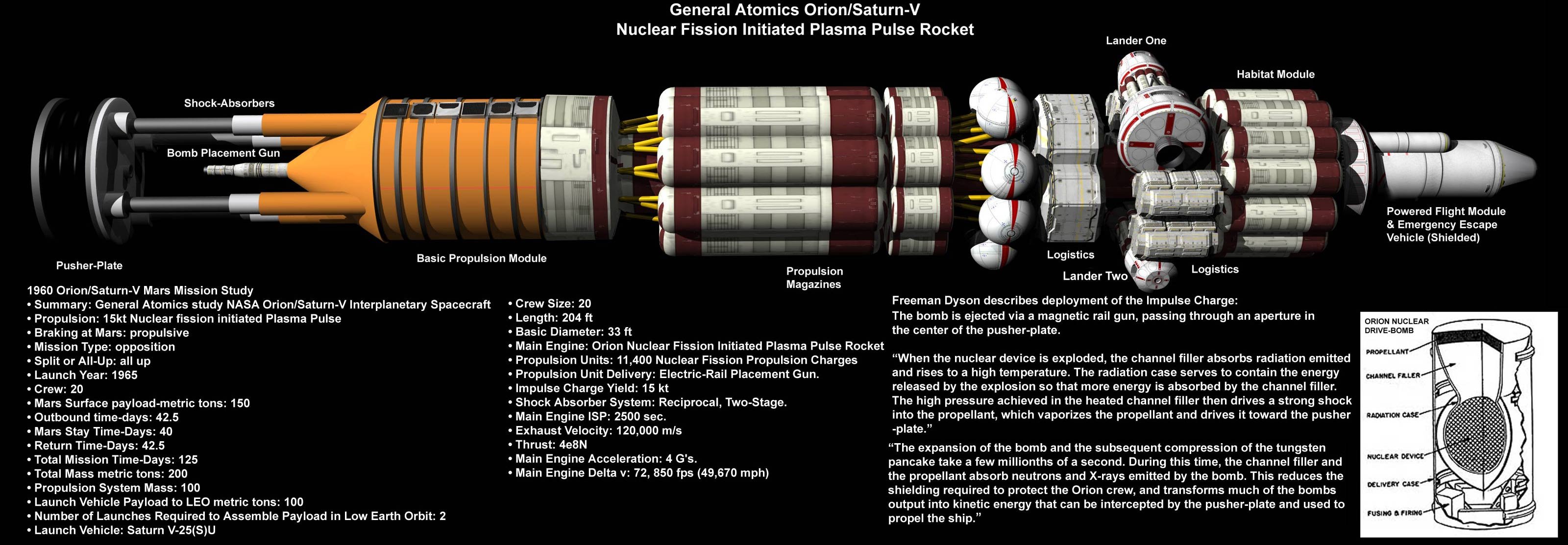

The concept was at once simple and wildly audacious. Small coffee can sized nuclear "bomblets" would be rapid fired by a railgun out the back of the Orion vessel. They would pass through a narrow hole in the "pusher plate", the shock absorbing barrier that would catch the brunt of the resulting nuclear blast. The vessel would then ride that blastwave forward. The next bomblet's explosion would add momentum to the vessel, then the next and so on, with pores in the pusher plate re-applying a new thin layer of protective graphite oil between each blast.

It was designed during the "anything goes" era of nuclear technology, largely on account of the cold war. However insane and over ambitious this might seem, the math checks out. It is absolutely feasible from an engineering standpoint. Just not from a political one. The Partial Test Ban treaty with Russia, which prohibits upper atmospheric nuclear detonations, resulted in the cancellation of the Orion project. It was then indefinitely mothballed, waiting for a more favorable political climate.

It did not especially help that the version of Orion shown to president Kennedy was armed to the teeth with nuclear missiles and howitzers. They severely miscalculated what sort of man Kennedy was when they presented him with that hypermilitarized mockup.

It's a terrible shame, too. Nuclear pulse propulsion makes it possible to achieve the speeds necessary to cross the vast distances between stars in under a human lifespan. Specifically, using modern thermonuclear bomblets, it would be possible to accelerate one of the larger Orion concept craft to one tenth the speed of light. At that speed, it would take 47 years to travel from our own solar system to Alpha Centauri, including the time needed to decelerate at the destination.

Orion can also be launched from the Earth's surface. It makes possible unprecedented surface to orbit payload capacities. You could basically send up an entire orbital colony in one launch. Some plans called for the pusher plate to be made of uranium so colonists could slowly cannibalize it for use in the colony's reactor.

This interested NASA intensely. They designed their own conceptual nuclear pulse propelled spacecraft, much smaller and more modest than Orion, intended to be assembled in orbit rather than launched from Earth. This would evade the partial test ban treaty but severely limit the size of the vessel, hampering its utility. Still, having a high speed reusable interplanetary shuttle, never meant to land on any planet, would make routine manned missions to any solid mass in the solar system a breeze.

Lament, then, for the starship that never was. Current approaches to nuclear propulsion favor nuclear thermal rockets, as the acceleration profile of nuclear pulse is very hard on the astronauts. To call it a "bumpy ride" would be a severe understatement, and general (appropriate) wariness of nuclear explosives turn many off to the idea.

If we dig Orion out of early retirement, it will likely be out of desperation. Orion's ability to launch an immense payload from Earth to orbit, then to accelerate it to a significant fraction of the speed of light gives us a powerful potential weapon against incoming asteroids. It is perhaps the only weapon we could leverage that, on short notice, would give us a fighting chance against that sort of threat.

It is also the only way we could get enough of humanity off Earth in a hurry to save our species if it turned out that the asteroid can't be stopped. The largest Orion designs, at 4,000 tons, could easily include all of the equipment necessary to grow a self sufficient food supply, to recycle waste water indefinitely, and in all other ways to keep the occupants alive for decades or even centuries.

So, the capability is there. Let's hope we never have to use it, and that if Orion vessels ever fly, it's because we pulled our heads out of our asses and decided to get serious about expanding our species into space. I pine for a future in which Orion vessels putt putt putt between destinations within the solar system setting up colonies and trading resources, while Orion probes are sent to promising exoplanets to get a closer look.