The colonization of the Moon is the proposed establishment of permanent human communities or robotic industries on the Moon. [wiki]

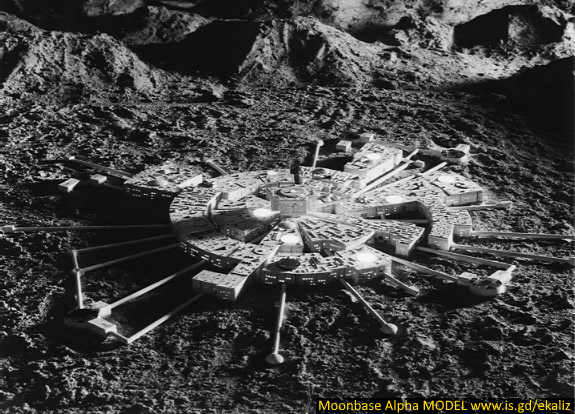

Photo is a MODEL 'Moonbase Alpha' from Geocities

"The US could lead a return of humans to the surface of the Moon within a period of 5-7 years from authority to proceed at an estimated total cost of about $10 billion," conclude NASA's Alexandra Hall and NextGen Space's Charles Miller in one of the papers.

A Summary of the Economic Assessment and Systems Analysis of an Evolvable Lunar Architecture That Leverages Commercial Space Capabilities and Public–Private Partnerships

Based on these assumptions, the analysis concludes as follows:

• Based on the experience of recent NASA program innovations, such as the COTS program, a human return to the Moon may not be as expensive as previously thought.

• The United States could lead a return of humans to the surface of the Moon within a period of 5–7 years from authority to proceed at an estimated total cost of about $10 billion (±30%) for two independent and competing commercial service providers, or about $5 billion for each provider, using partnership methods.

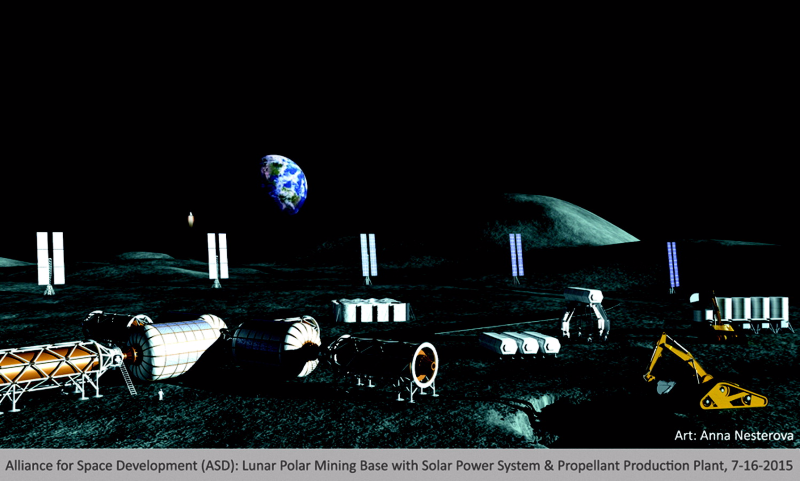

• The United States could lead the development of a permanent industrial base on the Moon of four private-sector astronauts in about 10–12 years after setting foot on the Moon that could provide 200 metric tonnes of propellant per year in lunar orbit for NASA for a total cost of about $40 billion (±30%). See Figure 1 for prototypical Moon base.

• Assuming NASA receives a flat budget, these results could potentially be achieved within NASAs existing deep space human spaceflight budget.

• A commercial lunar base providing propellant in lunar orbit might substantially reduce the cost and risk NASA of sending humans to Mars. The ELA would reduce the number of required Space Launch System (SLS) launches from as many as 12 to a total of only 3, thereby reducing SLS operational risks, and increasing its affordability.

• An International Lunar Authority, modeled after CERN and traditional public infrastructure authorities, may be the most advantageous mechanism for managing the combined business and technical risks associated with affordable and sustainable lunar development and operations. This model also provides a possible solution to reconciling the 1967 Outer Space Treaty with commercial development.

• A permanent commercial lunar base might substantially pay for its operations by exporting propellant to lunar orbit for sale to NASA and others to send humans to Mars, thus enabling the economic development of the Moon at a small marginal cost.

• To the extent that national decision-makers value the possibility of economical production of propellant at the lunar poles, it needs to be a priority to send robotic prospectors to the lunar poles to confirm that water (or hydrogen) is economically accessible near the surface inside the lunar craters at the poles.

• The public benefits of building an affordable commercial industrial base on the Moon include economic growth, national security, advances in select areas of technology and innovation, public inspiration, and a message to the world about U.S. leadership and the long-term future of democracy and free markets.

“When I was little, I dreamed of being the first woman on the Moon,” Hall said. “Maybe that’s unrealistic now. But I can use this amazing story of individuals who are passionate about space to have a big impact on education and public outreach. And from a purely selfish point of view, I’ll get to be in mission control when the rocket is launched and travel vicariously through it.”

READ THE PAPER --> http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/space.2015.0037