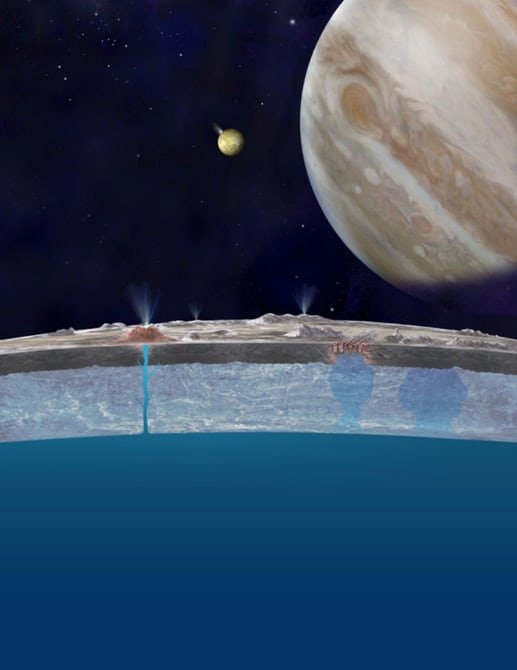

Jupiter’s moon Europa is a very intriguing body in our solar system for the exploration of life. When the Galileo probe examined the moon it discovered a disruption of its magnetic field, and the explanation that most scientists give for that disruption is that Europa has a huge saltwater ocean underneath its miles thick icy shell.

What do we know about Europa?

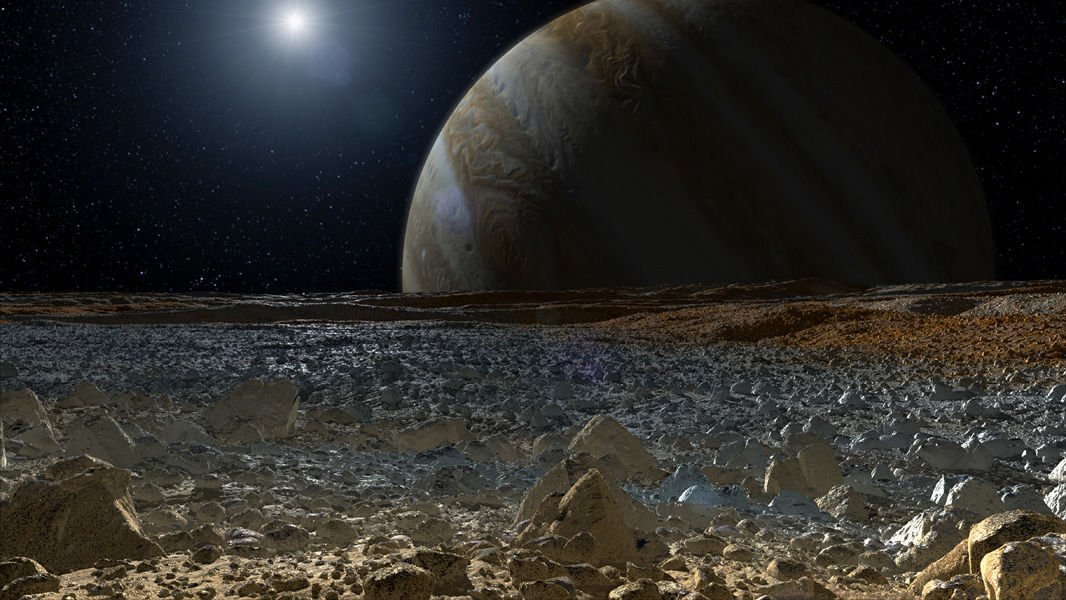

Europa was discovered by Galileo Galilei in January of 1610, around the same time as his discovery of Io, Ganymede, and Callisto – together known as the Galilean moons. Slightly smaller than our moon, it is tidally locked to Jupiter – which means one side always faces the large planet. But some research suggests that it might not be fully locked, and that could explain some of Europa’s features.

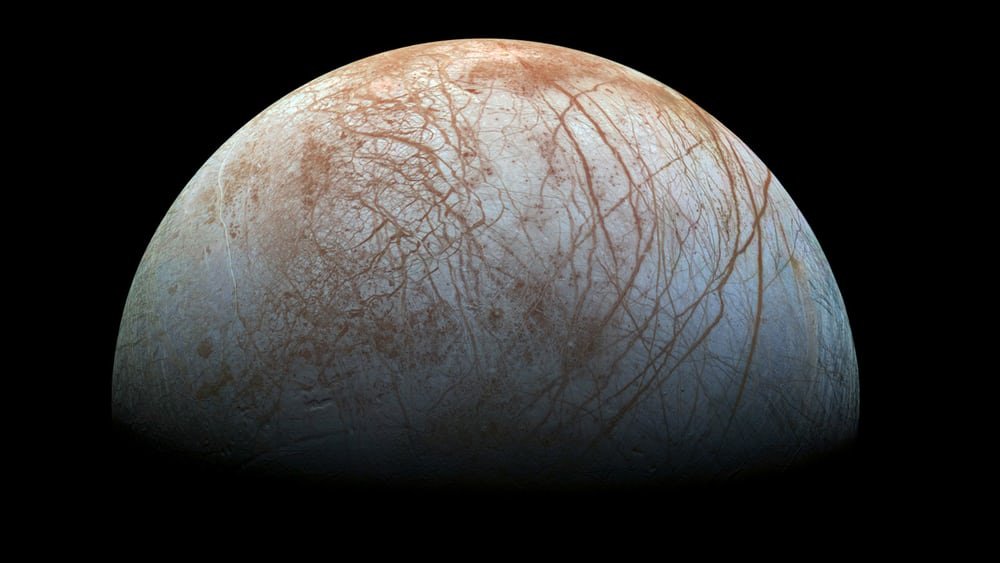

Europa lacks craters or mountains which lead scientists to believe that the surface is tectonically active and young. The most obvious feature of the moon are the long brown lines that run along its surface, these are called linea. These are thought to be caused by the stress of gravity from Jupiter and the other moons cracking the icy shell and depositing salt along the seams. This same push and pull of Europa is thought to create some heat in the ocean below, enough to keep it liquid.

Scientists have recreated this in a lab by chilling saltwater to -173C and then blasting it with electrons - simulating the radiation from Jupiter. After many hours the salt turned a similar brown color, and the longer the electrons were left on, the browner the color became – which they suggest could be used to tell the age of the lineae.

Europa has a thin atmosphere composed of oxygen created by the strong radiation of Jupiter in a process called radiolysis. These ultraviolet radiation particles collide with the icy surface and split the water into oxygen and hydrogen, much of the hydrogen is light enough to escape Europa’s gravity – which forms a gas cloud behind the moon as it orbits. The free oxygen and hydrogen can recombine with other materials to create basic life building blocks like carbon dioxide, hydrogen peroxide, and oxidants.

Recent evidence provided by the Hubble Space Telescope detected water vapor 100 miles above its surface. Independent studies have proven this by using the same method by which exoplanets are discovered – by detecting changes in light when it passes in front of Jupiter. The water plumes are sporadic, showing up in only 3 of 10 photos taken over the course of 15 months, but they are there and by some estimates went as high as 125 miles above the surface. But this lack of plumes in the other 7 photos indicate that the water eruptions from these cryogeysers are sporadic.

These observations are also pushing the limits of the Hubble, and astronomers are hoping that the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2018, will be able to provide more information by using the infrared vision capabilities it has.

Could it be possible for a probe to catch some of this vapor and analyze it?

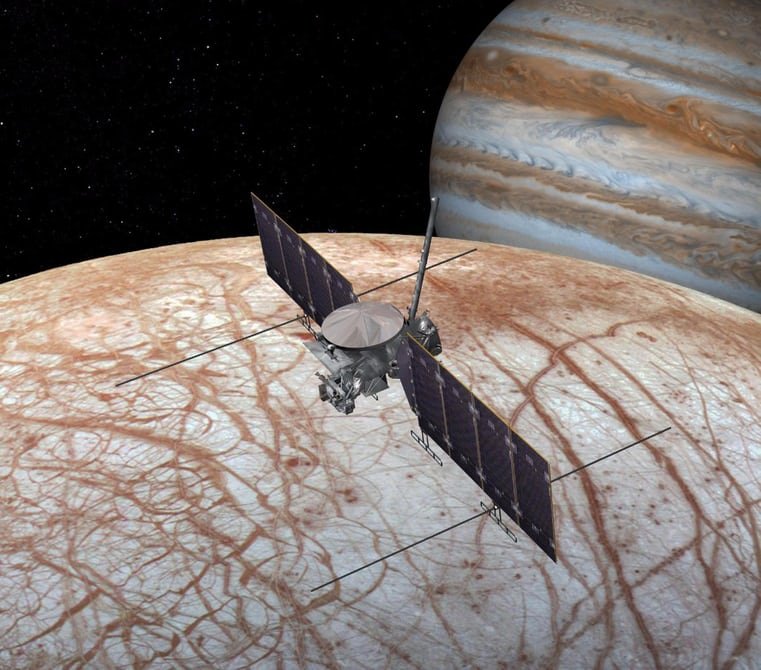

NASA has plans to launch the Europa Clipper mission to the moon sometime in the early 2020’s. After its several year journey it will perform up to 45 flyovers from anywhere between 16 miles up to 1700 miles above the surface. Using the nine scientific equipment selected for this mission it will be able to produce high-resolution photos and determine its composition. A magnetometer will more accurately detect the depth and salinity of its ocean. Ice penetrating radar will determine the thickness of its ice layer. Thermal equipment will determine the temperature of these ice plumes, checking for the possibility of an internal heat source from the interior in addition to the heat generated by the tidal forces.

Here is the exact list of scientific instruments to be aboard the probe:

- Plasma Instrument for Magnetic Sounding (PIMS)

- Interior Characterization of Europa using MAGnetometry (ICEMAG)

- Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE)

- Europa Imaging System (EIS)

- Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface (REASON)

- Europa THermal Emission Imaging System (E-THEMIS)

- MAss SPectrometer for Planetary EXploration/Europa (MASPEX)

- Ultraviolet Spectrograph/Europa (UVS)

- SUrface Dust Mass Analyzer (SUDA)

This also isn’t the only probe that will be launched to examine the moons of Jupiter. The European Space Agency is scheduled to launch its Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer in 2022 to arrive in 2030. This mission’s main focus is Ganymede, but it will perform multiple flybys of Callisto and make two passes of Europa as well.

Many scientists believe where there is water there can be life, so what about life on Europa?

“From an astrobiology perspective, Europa really brings together the three keystones for habitability, and that is of liquid water, access to the elements needed to build life, and potentially the energy needed to power life.” – Kevin Hand, NASA’s deputy chief scientist.

Some theories included ‘lakes’ locked inside the glaciers covering the surface could support life.

More popular theories in support of life on Europa state that deep oceanic hydrothermal vents could support life like on Earth – called extremophiles. This type of life obtains their energy from the chemicals released by these vents and create organic material through chemosynthesis. These organisms that feed off the chemicals released from the vents are then eaten by other animals and create the food chain.

If life of that nature is too advanced to be supported on Europa, there is thought that a life such as endoliths could be found. Endoliths are simple organisms (bacteria, fungus, algae, amoebas - microbials) that can live inside rock. This is how some scientists think life could have been transported there from asteroid collisions in a process called lithopanspermia.

One proposed way to get down there and check for life is what is known as the ‘meltbot’. Using nuclear energy it would melt itself down through the ice where it would deploy a hydrobot to travel around and gather information to beam that data back to Earth. This mission and others have been suggested for orbiters and landers as well, but none have been funded.

This has led some to propose that a manned mission be sent as soon as possible, the only catch is that it would be a one way trip. Objective Europa wants to send a crew to search for life there, while eventually giving up their own. A sacrifice for science.

Assuming that we can send a team all the way there with all the equipment they might need, and a way could be found to protect them from the lethal dose of radiation that they would absorb each day, and that the pressures at the bottom of the ocean up to 60 miles deep could also be handled – would it be worth it? What about the numerous unknown problems that will arise?

That is really the goal of Von Bengston, the creator of Objective Europa, he wants to put the problem out there and let the most brilliant answers be posted on their website. He says that the people in history were willing to die to explore, and people are sent off to die in wars all the time. So why not send some volunteers to die in the name of science?

The discovery of life created on another body, especially within our own solar system, would be the greatest discovery of all time. It would prove that life can be found elsewhere in the galaxy, a question that is at the forefront of numerous minds. Life on Europa would most likely have been created there independently of Earth, so that would point to life being pretty easy to develop if the basics are there. Would the possibility of an answer be worth a few human lives? Let me know your opinion in the comments down below.

And if you think you know a solution to any of these numerous problems, go ahead and post it over on their forums.