Stemchurch - Day # 3: Blessed are the meek because they will receive the land by inheritance

.jpg)

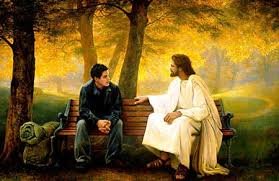

Who are the meek

The bliss on which we wish to meditate today lends itself to an important observation. He says: "Blessed are the meek because they will possess the land." As well; In another passage from the same Gospel of Matthew, Jesus exclaims: "Learn from me, for I am gentle and humble of heart" (Mt 11:29). From this we deduce that the beatitudes are not just a good ethical program that the teacher draws for his disciples; They are the self-portrait of Jesus! He is the true poor, the meek, the pure in heart, the persecuted for justice.

Here is the limit of Gandhi in his approach to the sermon on the mountain, which he also admired a lot. For him, he could even do without the historical person of Christ. I would not even mind, "he said once," if someone showed that the man Jesus really never lived and what is read in the Gospels is nothing but the imagination of the author. Because the sermon on the mountain would always remain true before my eyes.

It is, on the contrary, the person and the life of Christ that makes of the Beatitudes and of the whole sermon of the mountain something more than a splendid ethical utopia; makes it a historical realization, from which each one can draw strength for the mystical communion that unites him to the person of the Savior. They belong not only to the order of duties, but also to that of grace.

To discover who are the meek proclaimed blessed by Jesus, it is useful to briefly review the terms with which the word meek (praeis) is embodied in modern translations. Italian has two terms: "miti" and "mansueti". The latter is also the term used in the Spanish translations, the meek ones. In French the word is translated with doux, literally "sweets", those who have the virtue of sweetness

Each of these translations evidences a true but partial component of bliss. We must consider them together and not isolate any, in order to have an idea of the original wealth of the evangelical term. Two constant associations, in the Bible and in the ancient Christian genesis, help to grasp the "full sense" of meekness: one is that which brings together meekness and humility, the other that brings meekness and patience; the one brings to light the inner dispositions from which meekness springs, the other the attitudes that it impels to have regarding the neighbor: affability, sweetness, kindness. These are the same traits that the Apostle demonstrates when speaking of charity: "Charity is patient, it is helpful, it is not envious, it is not enriched " (1 Co 13, 4-5)".

Jesus, the meek

If the Beatitudes are the self-portrait of Jesus, the first thing to do when commenting on one of them is to see how he lived it. The gospels are, from end to end, the demonstration of the meekness of Christ, in its double aspect of humility and patience. He himself, we have remembered, is proposed as a model of meekness. To Matthew Matthew applies the words of the Servant of God in Isaiah: "He will not quarrel nor shout, the broken reed will not break it, nor put out the smoking wick" (Mt 12, 20). His entry into Jerusalem on the back of an ass is seen as an example of a "meek" king who flees from any idea of violence and war (Mt 21, 4).

The ultimate proof of the meekness of Christ is in his passion. No gesture of anger, no threat. "Insulted, he did not respond with insults; when he suffered, he did not threaten »(1 Pet. 2, 23). This feature of the person of Christ had been recorded in such a way in the memory of his disciples that St. Paul, wanting to exhort the Corinthians for something dear and sacred, wrote to them: "I beseech you for meekness (prautes) and kindness ( epieikeia) of Christ "(2 Cor 10: 1).

But Jesus did much more than give us an example of meekness and heroic patience; He made meekness and non-violence the sign of true greatness. This will no longer consist in standing alone over others, over the mass, but in descending to serve and uplift others. On the cross, Augustine says, He reveals that true victory does not consist in making victims, but in becoming victims,

.jpg)

.png)

Meekness and tolerance

The bliss of the meek has become of extraordinary relevance in the debate on religion and violence, ignited after events such as September 11. She remembers, first of all us Christians, that the Gospel does not give rise to doubts. There are no exhortations to nonviolence, mixed with contrary exhortations. Christians may, at certain times, have erred about it, but the source is clear and to it the Church can return to be inspired again in every age, sure of finding nothing but truth and sanctity.

The Gospel says that "he who does not believe will be condemned" (Mk 16, 16), but in heaven, not on earth, by God, not by men. "When they persecute you in a city," Jesus says, "flee to another city" (Mt 10:23); it does not say: "put it to iron and fire". Once, two of his disciples, James and John, who had not been received in a certain Samaritan village, said to Jesus: "Lord, do you want us to say that fire comes down from heaven and consumes them?" Jesus, it is written, "turning around, he rebuked them." Many manuscripts also reflect the tone of the reproach: "You do not know what spirit you are, because the Son of man has not come to lose the souls of men, but to save them" (Lk 9, 53-56).

With meekness and respect

But let us leave aside these considerations of apologetic order and try to see how to make the beatitude of the meek a light for our Christian life. There is a pastoral application of the bliss of the meek that begins already with the First Letter of Peter. It refers to the dialogue with the external world: "Give worship to the Lord Christ in your hearts, always ready to give an answer to all those who ask you for the reason of your hope. But do it with meekness (prautes) and respect "(1 Pet 3,15-16).

Two types of apologetics have existed since antiquity: one has its model in Tertullian, another in Justin; one is oriented to win, the other to convince. Justin writes a Dialogue with the Jew Trypho, Tertullian (or a disciple of his) writes a treatise Against the Jews, Adversus Judeans. These two styles have had a continuity in Christian literature (our Giovanni Papini was certainly closer to Tertullian than to Justin), but it is true that today the first is preferable. The Encyclical Deus caritas est of the current Supreme Pontiff is a shining example of this respectful and constructive presentation of Christian values that gives reason for Christian hope.

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)