Have you ever asked yourself the question, what if cells could remember things? Obviously, cells don’t have a mind on their own and the fact that apparently “mindless entities” can achieve such complex tasks when put together in tissues or organs it’s almost magical, the phenomenon it’s called emergence. If you think about it, a bunch of cells is writing this post right now and more cells are reading it. Anyway, some cells do have a memory of some form, we have known this for years that our immune system keeps track of the pathogens it encountered to act more promptly to quench future infections. For a while we thought that was it, we thought that memory was a perk exclusive of immune cells. But, Dr Shruti Naik and colleagues made recently an interesting discovery. They found that the regenerative potential of skin is enhanced when its cells have been previously exposed to chemical, microbial or mechanical stressors (Naik et al., 2017). Which implies that skin cells do have a memory too.

How can a cell remember without a brain of its own?

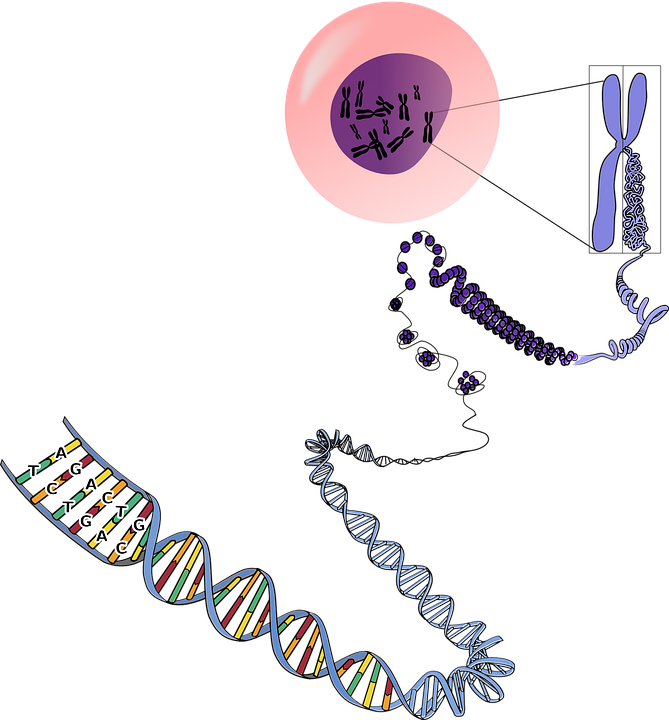

To understand this, we must have a look at how cells work. Everybody knows that cells contain DNA, lots of it and I mean a lot. If this doesn’t sound scientific enough I’ll give you numbers, to be exact each human cell contains about 6 picograms of DNA. You may ask, is that it? Well, if you were to stretch the DNA to its full length, it would be about 3 meters long and the amazing fact is that it’s contained in a small cell of only few microns (Ref Book 1). Every cell in our body contains the exact same amount of DNA, they contain all of it, even parts that they don’t need. For that to be possible, cells have to package the DNA into a compact, denser form called chromatin using proteins that bind DNA, creating the biological equivalent of a zip file. Now, DNA is basically the cell’s recipe book that contains all the info necessary to make a protein, the portion of DNA that contain the info to make a full protein is called gene. Like when you open your recipe book (assuming that you are not looking it up on youtube from your tablet), you must search for the right page, so the cell has to “unzip” the DNA in the right region, copy the gene and translate it into a language readable for its protein-making machine. Please note that I am really oversimplifying, if you want to read more in detail about this process I suggest you to check-out this reference (Ref Book 2).

Again, like when you use your recipe book, if you open it always at the same page, somehow over time this page will be easier to find, you may reach a stage where you just throw your book in the air and it will land on the right page (I really hope you are nicer to your recipe books than me). So, what Dr. Naik discovered, is that when skin cells, or to be specific, epithelial stem cells (EpSCs), are activated during inflammation, many regions of their chromatin become more open. This means that all the genes comprised in these regions are more likely to be expressed. The surprising part was that these regions of the chromatin remained opened long after the inflammation was subsided. Most of the genes comprised in these regions encoded for proteins that actively participate in healing, thus these cells now confer a healing advantage (Naik et al., 2017).

In other words, these regions of open chromatin were acting as a “memory” for the cells. Now we must understand that when a cell replicates, all its chromatin gets disassembled and reassembled, erasing all the previously open regions (Margueron & Reinberg, 2010). This means that for the skin tissue to really retain this memory, it must contain a subset of cells that do not actively divide or that at least have a low proliferation rate. We know for a fact that skin tissue have several different types of EpSCs (Takeo, Lee, & Ito, 2015) and these also have different proliferation rates (Fuchs, 2009).

The interesting part is that what was observed for the EpSCs could also occur among stem cells in other tissues, thus inflammatory memory could be a much more prominent phenomenon that we had anticipated.

But what are the clinical ripercussions of such cell memory?

You must think that having the “healing genes” always activated must be a good thing right? Not exactly, because tissue healing is a delicate process that must be carefully orchestrated between the stem cells, the surrounding cells and the immune system. Anything that alters the balance risks of causing complications such as cancer. So having EpSCs with lingering memory of inflammation may cause cancer (Mantovani, Allavena, Sica, & Balkwill, 2008) or even fuel further inflammation in a self-perpetuating process that may end up with chronic inflammation (an example would be the insurgency of psoriasis). In a more extreme case, the hyper-activity of these “memory” stem cells may cause stem cell exhaustion and premature ageing.

I did not want to sound too negative or to scare you, my aim was just to emphasize how delicate is the balance in our body. Anything that disrupts the delicate interplay between the cells that participate in tissue healing can cause a lot of problems. It is true that sometimes too much of a good thing is a bad thing.

References:

- Fuchs, E. (2009). The tortoise and the hair: slow-cycling cells in the stem cell race. Cell, 137(5), 811–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.002

- Mantovani, A., Allavena, P., Sica, A., & Balkwill, F. (2008). Cancer-related inflammation. Nature, 454(7203), 436–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07205

- Margueron, R., & Reinberg, D. (2010). Chromatin structure and the inheritance of epigenetic information. Nature Reviews. Genetics, 11(4), 285–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2752

- Naik, S., Larsen, S. B., Gomez, N. C., Alaverdyan, K., Sendoel, A., Yuan, S., … Fuchs, E. (2017). Inflammatory memory sensitizes skin epithelial stem cells to tissue damage. Nature, 550(7677), 475–480. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24271

- Takeo, M., Lee, W., & Ito, M. (2015). Wound healing and skin regeneration. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 5(1), a023267. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a023267

- Ref Book 1: Mitchel, Campbell Reece. Biology Concept and Connections. California, 1997

- Ref Book 2: Molecular cell biology - Lodish 2016