A New Series

This is my first science post. I intend this to be the first episode in an "introduction to biology" series, a sort of Biology 101. I chose biology because it's my favorite hard science, the reason being that it's more anthropocentric than the other hard sciences. And I, being a selfish anthropos, like whatever revolves around me. If the sun won't do it, a science might!

Source

Yellow ball = me. Blue ball = biology.

What is life?

If, as almost all textbooks (and its etymology) tell us, biology is the study of life, then what is life?

Biologists often attempt to define life by its properties: living organisms reproduce, they evolve, they consume energy, they respond to stimuli, they grow, and so on (see, for instance, Concepts of Biology, pp: 6-9.)

Are the conditions sufficient?

A fire reproduces, consumes matter to feed itself. A snowball rolling down a slope can grow. A universe might evolve. A black hole consumes energy. So does my smartphone, faster than I'd like. I respond to flame by retracting my hand, but so does the flame when I pour water at it. Yet fires, universes, black holes, and smartphones are not alive.

Are the conditions necessary?

A woman after menopause can't (normally) reproduce, but that doesn't make her dead. Nor can variocele surgery bring men back to life. The last living dinosaur was unable to breed, but it wasn't exactly dead (though it would soon be).

Beyond the actual

And all the examples I gave are real. I didn't even go into "what if" scenarios. A scientist could certainly make up his mind to create a robot that would satisfy all conditions for life.

Source

"Of course I'm alive. Here's my ID. I'm Turing-certified and everything," the robot stated in an interview.

Plus, we don't even know whether viruses are alive. And NASA had to widen its net (its definition of life) in order to increase its chances of catching some aliens.

The Plan

So where does this leave us? (As far as I'm concerned, something is alive if it possesses consciousness. But that's a different – and more complicated – story.) Myself, I'm a fan of dialectics: I believe debate and juxtaposition lead to higher retention rates, and make learning easier, funner, and deeper. For instance, juxtaposing Lamarckism (the theory that acquired characteristics, like scars, can be passed on to offspring) to Mendelian inheritance (the theory that "you're wrong, Lamarck!"), can help us grasp these concepts better than if they were presented to us alone, like a single fighter in a boxing ring. That would be boring. That would be rote memorization. We might imagine a student crying: "I want a fight, damn it!"

So what I propose we do here, is answer the question "What is Life?" through revisiting the old biological rivalry between mechanism and vitalism: the theory that life is something over and above simple chemical and physical processes, something completely distinct from inanimate matter. And we will do this, via a case study of the research that landed Eduard Buchner the 7th Nobel Prize in Chemistry. So, without further ado, I give you the man who killed vitalism!

Source

"The work on which I have to report lies on the boundary between animate and inanimate nature." - Eduard Buchner

Vitalism VS Mechanism

Is there a "living principle" in addition to mechanics? Is it life qua life that makes certain things happen, or can everything be reduced down to chemistry? Vitalism is the idea that certain processes can never be carried out by inanimate nature. Fortunately, unlike many other theories of its ilk, vitalism was falsifiable! This made it scientific: it was possible to conduct experiments that would disprove vitalism, since vitalist scientists of the 19th century "predicted that organic materials could not be synthesized from inorganic components".

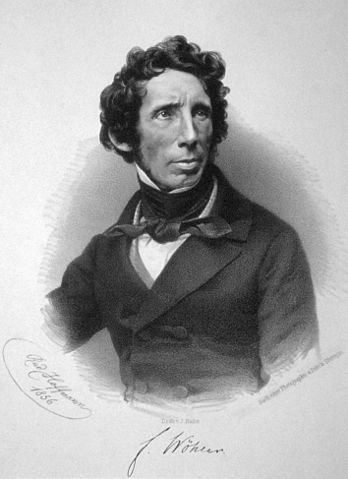

The unsung hero

Friedrich Wöhler, in 1828, succeeded in artificially producing urea, thus smashing the formerly held idea that urea could only be produced in animal bodies, under the influence of "the life force" (Cell-free fermentation, p. 105). However, no one seemed to pay any attention, since vitalism, true to its name, remained alive despite this achievement. Vitalism therefore remained the prevailing dogma.

Source

"I'm still mad at you," Wöhler stated in an interview with the author conducted via a medium.

Enter fermentation

Fermentation - that beautiful process that gives us beer and wine among other things - was destined to become the battlefield on which the fates of vitalism and mechanism would be decided. "Fermentation was seen to be a physiological act inseparably linked with the life processes of yeast," Buchner stated in his Nobel Lecture. The mechanistic theory - in this case the enzyme theory - enjoyed great favor, but zero successes. "[E]very attempt made to separate such an enzyme from the yeast cells had failed." "[E]ven [Louis] Pasteur himself, the great experimenter had no success." (Cell-free fermentation, p. 107.)

Trying to get at the machinery inside the yeast, scientists threw everything they had at it. They boiled it, crushed it, doused it with various chemicals (ibid. pp. 108-9). But to no avail. As Buchner says in his Nobel lecture: "Lüdersdorff in Berlin had, as far back as 1846, crushed yeast cells on a sheet of ground glass with the aid of a glass roller, a task which, however, took an hour for 1 g of yeast. When dextrose was added to the pulp thus obtained, 'not one single bubble of gas' was given off, and the vitalistic theory thus seemed confirmed."

Rats! What can be done! I guess it's off to ebay to buy us some good yeast-crashing equipment.

Age of the machines

Source

Aptly named.

What you're seeing above is basically a mechanized pestle that, with the help of sand, can pulverize yeast to get at the magical "vitalistic" stuff inside. With the device pictured above, this can be done within a few minutes. The result is then added to a hydraulic press, where 500 cc of liquid can be obtained from 1000 g of yeast, to create "pressed yeast juice", which Buchner merrily handed around to the audience of his Nobel lecture. Lastly, "[i]f sugar solution is added to freshly expressed yeast juice, a strong formation of gas sets in after a little while." Thus, Buchner had succeeded in showing that fermentation can occur without living organisms, just enzymes.

Source

What is it with the early 20th century and self-explanatory machine names?

Piece of pie?

I made it sound easy. Science rarely is. It took Buchner alone decades and dozens of distinct experiments to get these results. But his work paid off. "If we now summarize the results of all these experiments, we establish that a separation of the fermentation effect from the live yeast cells can be carried out. [...] The active agent in the expressed yeast juice appears [...] to be a chemical substance, an enzyme, which I have called 'zymase'. From now on one can experiment with this just as with other chemicals." (Cell-free fermentation, p. 113)

And thus vitalism was pronounced dead: "Just as it was earlier learnt how to produce urea without a living animal, in the test tube, without any life force, so it is seen here that an apparent action of live cells can take place without cells." (Cell-free fermentation, p. 119) And, conversely, mechanism was crowned victorious: "We are seeing the cells of plants and animals more and more clearly as chemical factories." (ibid.)

Conclusion

Hopefully my approach will have given you an idea of what life might be, by stating what it definitely is not: it's not something that can do things inorganic matter can't. Life is purely material and mechanical. Any attempt to say that life is something over and above, will - if history is to be trusted - lead to the dreaded "ne plus ultra", a "go no further", a "science stops here". In Buchner's words:

Even though we may still be a long way from our goal, we are approaching it step by step. Everything is justifying our hopes. We must never, therefore, let ourselves fall into the way of thinking "ignorabimus" ("We shall never know"), but must have every confidence that the day will dawn when even those processes of life which are still a puzzle today will cease to be inaccessible to us natural scientists. (Cell-free fermentation, p. 105)

Study questions

- Do you think life is better defined positively or negatively? By stating what is is, or what it is not?

- Can we ever define life in such a way as to exclude all non-life, and to include all life? For instance, if we define life as DNA-based, do you think non DNA-based life is impossible?

- Do you think life is mechanical? If yes, how mechanical are we? In his title song of his album Mechanical Animals, Marilyn Manson says, "If we cry we will rust". I’m pretty sure that is completely unrelated to what we've discussed here, but feel free to comment.

Sources Cited:

Are Viruses Alive?

Boundless Biology

Cell-free fermentation

Concepts of Biology

Defining Life: Q&A with Scientist Gerald Joyce

Dialectic

Lamarckism

Mendelian inheritance

Necessity and sufficiency

Penn State physicist poses theory of evolving universe

Varicocele

Vitalism

Notes:

Dinosaurs didn't actually die off. They evolved into love birds.

steemSTEM is the go-to place for science on Steemit. Check it out @steemstem or visit on #steemSTEM in steemit.chat ( https://steemit.chat/channel/steemSTEM )

DeepThink is the go-to place for the humanities on Steemit. Check it out @SteemDeepThink or visit on discord ( https://discord.gg/7qyarFD )