When you think of an Egyptian Pharao you probably have a certain picture in your mind: the blue-golden-stripes of the King’s headdress, the crossed arms position, and the straight looking full of confidence – a King’s behaviour, simply said.

The term ‘Pharao’ is deeply connected with kingship in Ancient Egypt, but did you know what it really meant? It was written in hieroglyphs like this: 𓉐 𓉼 = transliterated = pr ꜤꜢ = spoken [per-aA] = means ‘the great house’! So the king was the exclusive authority to provide a house or home for his people! By leading the people of the ‘two lands’ (Upper and Lower Egypt) in a supportive way he was allowed to have been named the per-aA, the PHARAO.

The Egyptian Language is quite complicated, so I want to teach you a bit of reading hieroglyphs in future posts. But today I want to give you a brief insight into the pictorial expressions of the Ancient Egyptian Pharao.

Vestments of a King

The Crown

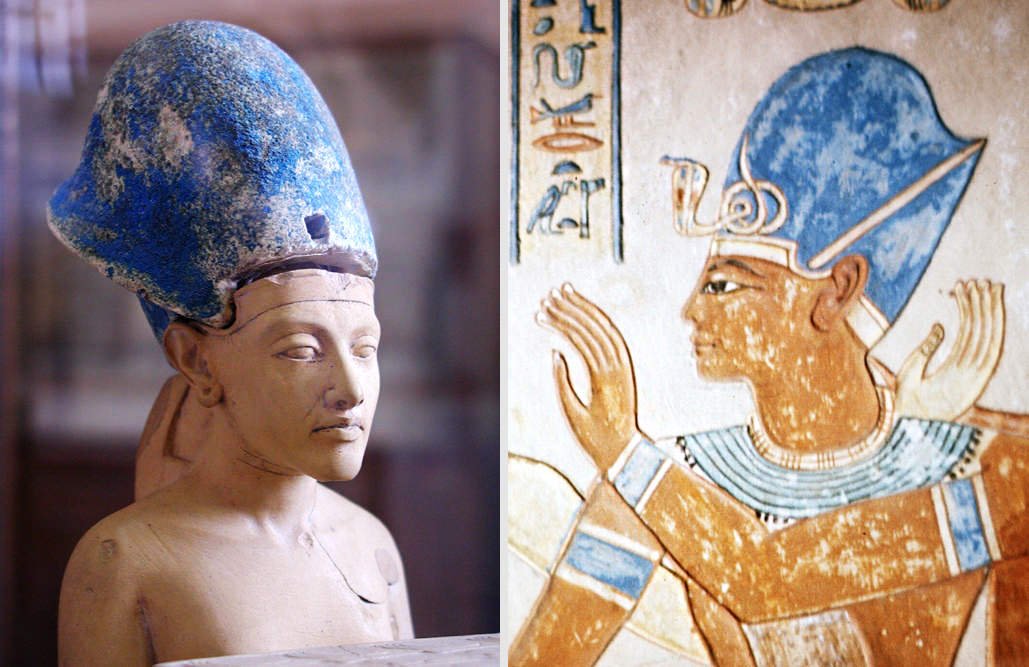

The Blue Crown

There were many other crowns used by the kings and one important example that were mostly used in times of war was the blue crown: 𓋙. We can see this in pictures of Pharao Tutankhamun as well as Akhenaten.

Image 2b (right): Ramses III. in the tomb of Amenherkhepshef, QV 55, Luxor, Queens Valley.

The ‘Nemes’

The well known pharaonic headdress is called ‘Nemes’. It is still controversial discussed what it really meant and how it was worn. In TV documentaries you see often just a scarf with blue and yellow or golden stripes thrown over the head. But as you can see on the following picture of the famous mask of Pharao Tutankhamun, the Nemes was bound together on the backside like a braid.

Another interesting fact might be that Egyptologists never found an archaeological evidence of a real existing crown or a nemes.

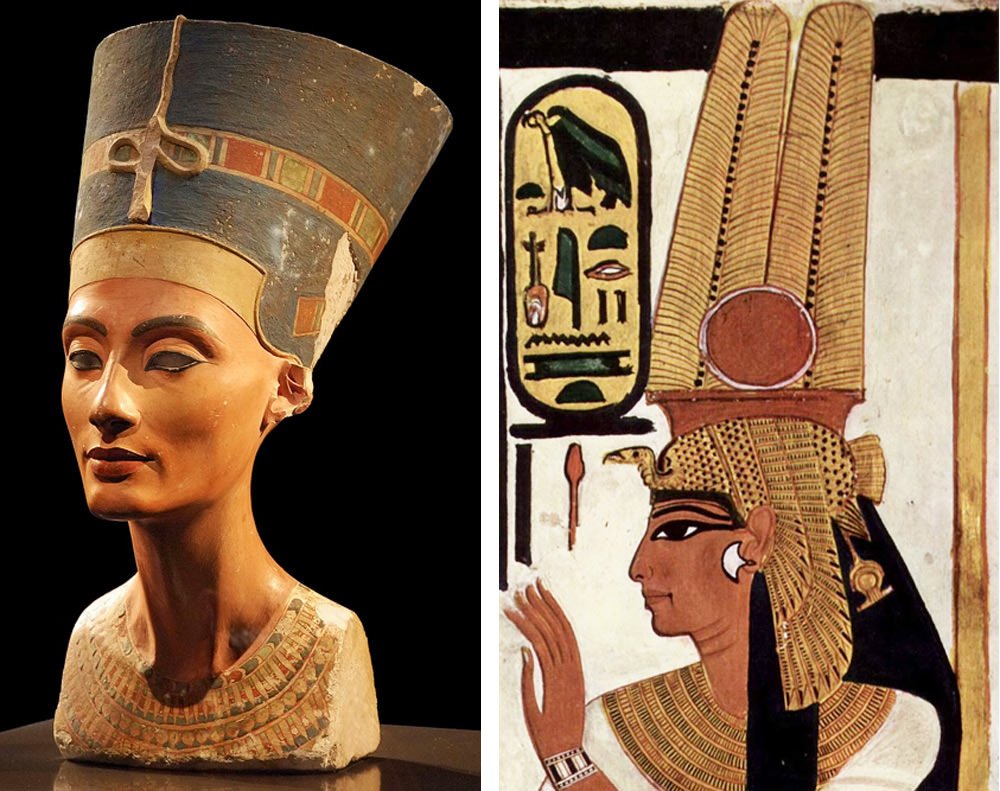

Women in high positions such as the royal wifes or daughters often wore headdresses that can not be considered as crowns but at least as a sign of the elite.

The Beard

There are two so-called ceremonial beards: the straight one and the bent one. When you see a picture with a Pharao that has a bent beard, it means the deceased King is depicted! These beards were generally false beards, that were fixed on the chin.

The beard was so important that even female leaders like Hatshepsut put on an artificial beard to show she was the first ‘man’ of the state. But, although she was acting and looking like a man, she still considered herself as women, which is shown by using the female grammatical form in her name and elsewhere. In other words: SHE was still called a SHE and not a HE. ;)

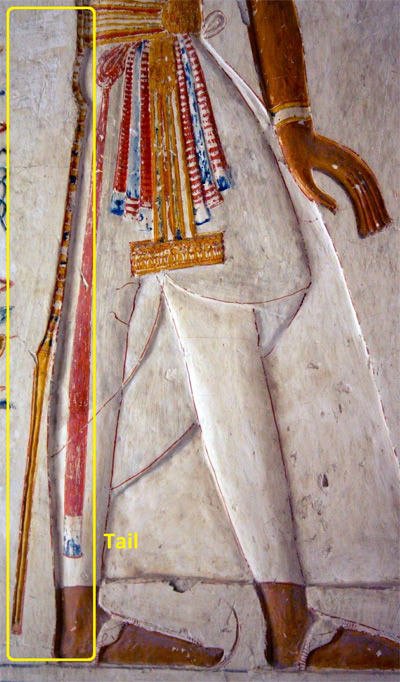

The Crook and the Flail as Scepters

Pharaos had often a so-called crook or ‘crosier’ in his hands. The name of this was ‘heqa’ and is seen by most scholars as a shepherd’s crook and meant ‘to rule’. But the hieroglyph heqa 𓋾 also was used as the word for ‘magic’. The God Osiris used the crook in the death court to judge over the deceased and decided if their Ba, the moving part of the soul, would be able to pass easily to the afterlife.

The flail 𓌅 , often crossed with the crook, is also a sign of the Pharao being the ‘shepherd’ of his people and is seen to be actually as a fly whisk.

Image 7b (right): Ushebti figure of Tutankhamun, Egyptian Museum Cairo.

Like a Boss King

The Animal’s Tail

Don’t mess with the Pharao

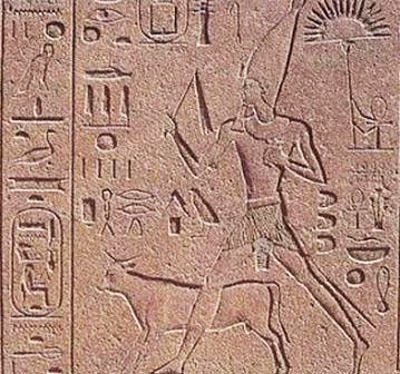

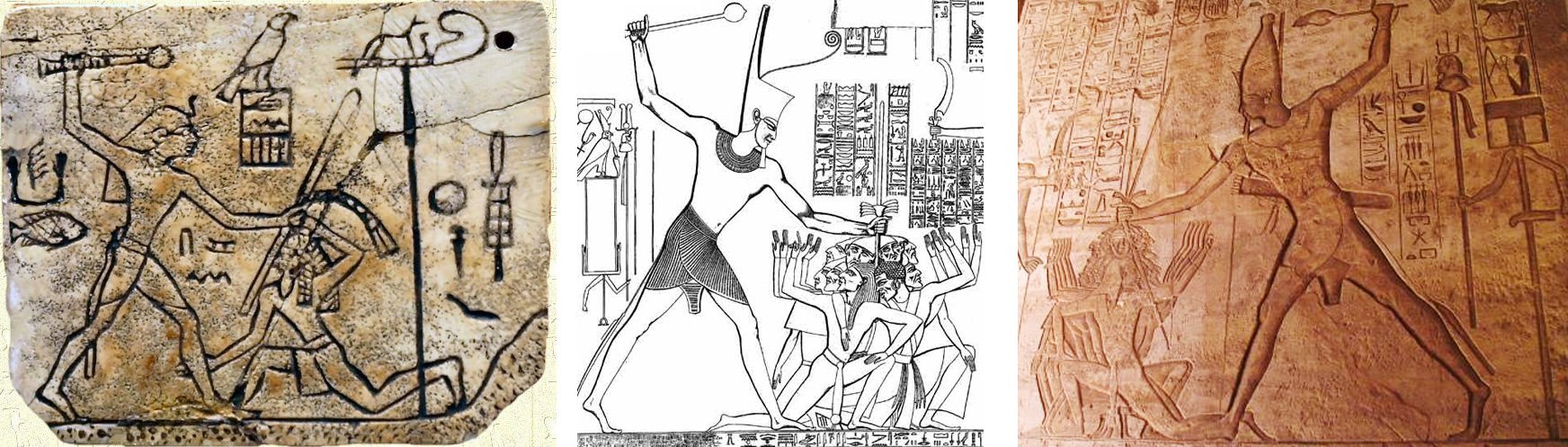

The Ancient Egyptian percieved their own country as the centre of the world. Everything that was not Egyptian was considered ‘outside of their peaceful environment’. When it came to conflicts with intruders from other countries such as from the north or from the south (less from the west because of the huge desert area), the Pharao had to make sure that this ‘egyptian world’ was safe. He had, of course, to defend Egypt against the foreign invasion. This is depicted in the often used motive of the ‘Beating of the Enemy‘. You can see this in many variations but always with the same message: the great Pharao (in much bigger size as his opponents) grip the enemy or enemies on their scalp(s) or and erect the other hand, holding a weapon, that is going to swing down on them.

Image 10b (centre): Drawing of Pharao Seti I.

Image 10c (right): Ramses II., Abu Simbel.

Sources and further reading:

• Budge, E. A. Wallis (Ed.): The Book of the Dead. The Papyrus of Ani in the British Museum. Longman, London 1895.

• Staehelin, Elisabeth, in: Lexikon der Ägyptologie IV, 1982, cols. 613–618, s.v. Ornat.

• Fischer, Henry G., Notes on Sticks and Staves in Ancient Egypt, Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 13 (1978), pp. 5-32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1512707

• Hilliard, Kristina / Wurtzel, Kate, Power and Gender in Ancient Egypt: The Case of Hatshepsut, Art Education, Vol. 62, No. 3 (May 2009), pp. 25-31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20694765

• Uphill, Eric, The Egyptian Sed-Festival Rites, in: Journal of Near Eastern Studies 24, 1965, No. 4, pp. 365–383.

• https://dornsife.usc.edu/what-is-a-king-to-do/historical-context/

• http://www.arabworldbooks.com/egyptomania/sameh_arab_sed_heb.htm

Images:

Image used in the editorial picture: Source

Image 1: Source / Image 2a: Source / Image 2b: Source / Image 3a: Source / Image 3b: Source / Image 4a: Source / Image 4b: Source / Image 5a: Source / Image 5b: Source / Image 6: Source / Image 7a: Source / Image 7b: Source /Image 8 Source / Image 9: Source / Images 10a–c: Source

Feel free to ask all the question of what you always wanted to know about Ancient Egypt. That’s my job and my passion. Let’s discuss your thoughts and ideas.

If you liked this article, please follow me on my blog @laylahsophia. I am a german Egyptologist writing about ancient and contemporary Egypt, history of science, philosophy and life.