For medical students, writing a clinical history for the first time can be a moment similar to losing your virginity: full of confusion, with doubts about what to do despite knowing the theory, and after some time it will be a shameful memory about which you do not want to tell the whole truth. It is true that we all receive classes during our studies on its correct formatting, but when you get to the internships, you will find that (at least in my case) they only taught you how to fill a part, and you will go through that kind of initiation in which you will have to find a resident doctor with enough patience and free time to explain the rest to you.

You may know what to ask the patient during the anamnesis (fancy word for the medical interrogation), and in what part of the history to write down that data, but the order of the studies, the physical examination, the medical orders, and other components is generally not part of the explanation given during the studies. It is something like taxes and everything related to banks; something that at no time they explain to you in classes, and that you are supposed to learn for yourself after being thrown into the cold and uncaring outside world. But not everything is bad, I am to help you, and be your ray of light amidst the darkness, in exchange for just one UpVote (shameless self-promotion, the road to success in Steemit? Remember to reread this post in a few days to find out).

Now, leaving the obligatory introduction aside, let´s get to the topic at hand: as you surely know, a clinical or medical history is a medical-legal document that collects all the information about the patient and his case, following a strict chronology and with a certain order to facilitate reading in times of emergency. It not only talks about the patient's current illness, it also contains details about important previous illnesses, the procedures that have been practiced, and legal consents to avoid those lawsuits that have become so fashionable. The order can vary from country to country, from one service to the other, and even from hospital to clinic, but the most commonly used in my country, and the one I consider most practical, is the following:

1. Arrival Summary

Every undergraduate intern will quickly learn how to write this part; his first on-call services will usually consist of writing dozens of ingress summaries until resident doctors trust him enough to let him get closer than 10 meters to a scalpel or suture kit. It consists of 4 parts: It begins with the Chief Concern, abbreviated as CC, which is the reason for the patient to go the assistance center, written as he or she says; with or without medical terminology. If the patient arrives describing his illness as "a stuck turd" (based on a true story), that is what is written down, thus preventing any seriousness during case reviews. Then, follows the History of Present Illness, abbreviated as HPI, which is the description, now with medical terms, of the patient's case at the time of his arrival; the name and age of the patient is written, their origin (where were they born and where do they currently live) and occupation, important pathological antecedents, and their history of how their illness began, with as much detail as possible and in chronological order from the onset of the disease to the present time.

After the HPI, comes the Physical Examination at the time of entry, it has to be done as detailed as possible, with an emphasis on the affected systems. It begins with the subjective part, questioning the patient about the symptoms that he presents and usually about his defecations and urination (unless it is considered not pertinent, it matters little the last time a patient with 3 firearm injuries went to the bathroom), and then proceed with the objective part, a system-by-system, cephalo-caudal examination (from head to toe), also taking note of the vital signs and general condition of the patient. Finally, the Entry Diagnosis is written, although this can also go before the physical examination, after the HPI. Here simply (and obviously) goes the apparent diagnosis, subject to changes after further evaluation.

2. Paraclinical Tests at Time of Entry

These are basically the laboratory tests that the patient brings, mostly seen in the internal medicine, obstetrics and pediatrics services; they are rare in surgery, because of the sudden nature of most cases. Few people have a complete hematology in their pocket in case someone decides to run over them with their truck.

It should be noted that these paraclinics usually have a set order: first, the electrolyte test, then the hematology, followed by the urine analysis, the X-rays, the routine electrocardiogram that is practiced on most patients, and after that other special tests such as ultrasounds or electroencephalograms

3. Hospitalization Evolution

Depending on how long the patient is hospitalized, this section can be as long as the bible written in ancient Aramaic. Here all the important changes in the state of the patient are written; each time a new laboratory test arrives, if there is a change in diagnosis or treatment, and the notes that usually appear at the end of the reviews with the specialists, all in chronological order. It is very important that it is well updated and complete, to avoid having to read the daily evolutions to be aware of the case.

4. Patient's Background

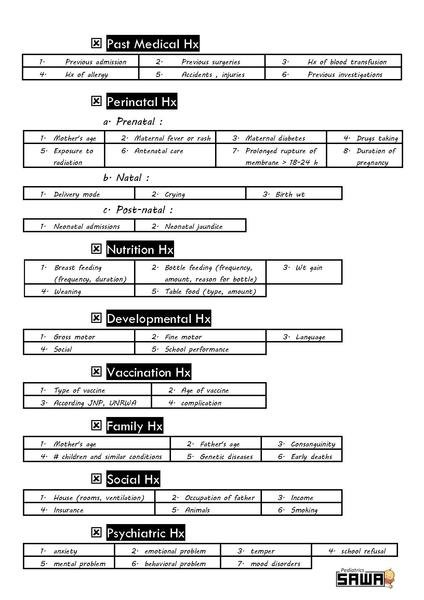

As the name implies, here goes the relevant data of the patient and their environment, starting with the personal background, such as previous diseases, surgeries, and drug allergies, then the family history, where they are asked about their parents, siblings and children, about whether they are alive, if they have any disease, and if they have already died, what was the cause, followed by the epidemiological background: where the patient lives, in what type of housing, if they have pets or vermin in their home, if they receive basic services such as electricity and water, etc., and finally the psychobiological habits, consumption of coffee, tobacco, alcohol and drugs. The latter can be a bit difficult to extract, unless the patient is very honest or very libertarian.

Example of the patient’s antecedents in a pediatric clinical history

5. Current Paraclinicals

In this section goes all the laboratory studies that have been done to the patient after their hospitalization, following the same order as the entry paraclinicals. I wish all the parts were as easy to explain as this one, putting it together may be one of the easiest things you will do in you internships, except if you have the bad luck of having to transcribe the handwritten original (though I assume that happens mostly here in Venezuela, where most documents are made by hand and in recycled papers), and it just so happens to be written with the classic handwriting of a doctor, requiring a trained team of cryptologists for its translation.

6. Current Physical Exam

All undergraduate interns will familiarize themselves very well with this part of the story, if you do not know how to write a medical evolution with your eyes closed at the end of the 4th year of studies, do yourself a favor and choose another career. Here goes the physical exams in the form of the daily evolutions that are made to the interned patients, ordered in chronological order; always the most recent ones first, followed by the oldest ones. How complete this exam will be depends on the service under which the patient is hospitalized; In internal medicine they are usually complete and system by system, with emphasis on the relevant positives, while in surgery they are more to the point, placing only what is important, for example. In all services the patient's vital signs are taken daily, however, remembering to avoid the temptation to put a blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg without measuring it to the patient. Come on, it only takes a minute.

Am I the only one who finds the Korotkov sounds oddly relaxing?

7. Current Diagnosis

It goes immediately after the daily examination, usually beginning with the most serious disease, and ending with the pathologies by antecedents or those that are controlled. It is important to remember that while a student can, and regularly is the one who writes the evolutions (at least in here), only a doctor can change the diagnosis. If you find it hard to believe that the male patient in room #401 has an ectopic pregnancy, it does not matter, it is not your duty to correct that.

8. Medical Orders

Put simply, this part is the patient's treatment, and the steps to be taken in their care. Here all the medicines are placed with their respective doses and indications, the type of diet that they must have, and other special care that they must receive, as well as the medical order in case the patient has to be transferred to another service. This section should also be in chronological order, and obviously can only be written by a doctor. It also has the peculiarity of being the most difficult to read; Good luck trying to understand names like Ceftriaxone written in the classic doctor's handwriting.

I hope that this small tutorial has been helpful, and that facilitates a little your first days of internships, you will have enough suffering later. And again, I reiterate that this format is the one we use in my country, but it varies according to where you are, so feel free to leave in the comments the format used in your hospital, it will be interesting to know how clinical histories are made elsewhere. So, you already know how to fill a clinical history, now you only need to understand it, and be able to know why that patient with an exploratory laparotomy presents pain in the left shoulder, or why the young woman with systemic lupus erythematosus and a Hodgkin´s lymphoma also has echolalia. *Sigh*, study Medicine, they said, it will be fun, they said...