This is a going to be a post about vaccines, but has has no real need to be. At its heart we’ll be talking about risk, and how we think and act based on the perceptions that we form towards what is likely to cause harm. If you don’t like vaccines, that's fine, you could easily go through this post and exchange the word vaccine with the word seatbelt and the word disease with trauma from car crash, and it would largely get across the same concept.

As I’ve mentioned previously, I’m a psychologist that works in the field of vaccination. I don’t do any of that squidgy biology stuff to make the vaccines (although I do place trust in those that do), instead I look at public perceptions and beliefs towards the evidence based recommendations that are arrived at through the extent of their work.

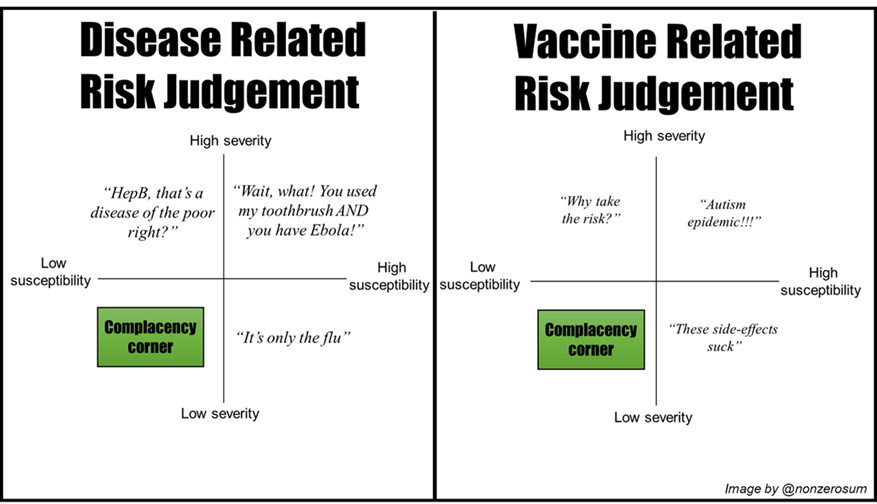

Vaccine related risk judgements

Vaccines are a medical intervention. They are a tool that the public health system uses to prevent disease (yeah, so this is about the level of medical knowledge you’re going to get out of me in these posts). When thinking about vaccines we therefore think in terms of two interconnected beliefs, those related to the vaccine and those related to the disease the vaccine aims to prevent. Now, it is important to understand that these beliefs that we form are judgements of risk and nothing more. As I mentioned in my previous post, it is near impossible to stay up-to-date on 100% of the science out there on vaccination, there are certain tricks that we can use to remain as accurate as possible on our judgments (i.e. trust in a healthcare system), but no matter who we are we still make judgements.

Each of these risk judgments are made on two dimensions. Susceptibility, how likely we are to experience a negative outcome and severity, how dangerous it would be to experience a negative outcome. Each vaccine is likely to be judge differently based upon what judgements an individual holds related to the specific vaccine and disease.

Here are some of the beliefs that might be held based on differing judgments.

For each disease/vaccine pair we can imagine each of our beliefs being a point somewhere on each grid. The higher the perceived severity/susceptibility of side-effects from the vaccine, and the lower the perception of severity/susceptibility of the disease, the higher the likelihood of vaccine hesitancy.

If we apply this as a likelihood across to our grid it may look something like this:

Place a point on each grid based on how you feel, combine the colours and compare it to the spectrum at the bottom and, job done, that's how likely you are to vaccinate.

Sadly not, there’s much more to risk perception than this, such as it being “fuzzy” and there being a difference between risk as analysis and risk as feeling. But for the time being let's just go with our simple model we have here and potentially revisit at a later time

Changes in risk judgements

Our perceptions of risk may change overtime through being exposed to new information. Information in this case might be statistical data related to how common a disease is in your local area, but it also might take the form of a story, such as that of a parent that believes their child's developmental disorder was caused by vaccination. The comprehension and processing this information may shift us in a certain direction on one of our grids.

A population wide example of this shift occurred in the winter of 2016 here in the UK due to two high profile cases of Meningitis B that became national news. At the time the MenB vaccine was only available (and cost-effective) for children up to the age of 6 months, the story of these two cases prompted a massive public demand for the vaccine to be made available for older children. Nothing had changed with respect to the diseases, it was still as prevalent and dangerous as ever however public perception of the disease had changed dramatically.

The introduction of an effective vaccine may change our perceptions in the opposite direction. As the prevalence of a disease reduces over the years our perception of susceptibility to the disease will, rightfully, reduce as a consequence.

This reduction of prevalence may have the additional consequence of less individuals within our local community contracting the disease and as such less stories being told about its severity. Take for example Polio, I’m willing to bet that many of you do not live in constant fear of you child spending their life paralyzed in an iron lung. In fact, in many countries the disease is fading from living memory entirely.

So wait a second, are you saying that people are right for not vaccinating?

Oh dear God no, this is what is so terrifying. One person not vaccinating, yes that's likely not going to have a massive effect, unless they travel to a country where the disease in question is still endemic. But hit a certain threshold of vaccine refusal and the the disease will bounce back and start causing mass suffering again.

This therefore is why in public health we often talk about vaccines being a victim of their own success.

The areas of the world with most hesitancy towards the vaccines are often the countries with the luxury of having low prevalence of disease. This safety becomes the new normal and the perception of threat may then move towards the vaccines instead.

There is a cycle at play here that we are trying to prevent, one in which requires effective communication between a health system and the public. If we were to rely on fear to take hold for each disease before people rationalise to vaccinate, then untold preventable suffering would occur. Instead we need to find ways in which the importance of vaccination are communicated before the re-emerge of diseases.

Obviously there is much more to the vaccine decision making process than risk perception alone. In the next post in this series the plan is to talk about how this process of risk perception is applied to who, where and why we place our trust.

Sources:

Earle, T. C. (2010). Trust in risk management: a model‐based review of empirical research. Risk analysis, 30(4), 541-574.

Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk analysis, 24(2), 311-322.

Reyna, V. F. (2012). Risk perception and communication in vaccination decisions: A fuzzy-trace theory approach. Vaccine, 30(25), 3790-3797.