...If I look at the one, I will.

There’s an old anthropology myth that primitive cultures counted: One, Two, Many. With many representing every number higher than two.

How many fish did you catch today? Many

How many stars are there in the nights sky? Many

How many myths are accidentally reinforced through poorly researched blog posts? Many

This has long since be debunked (so it’s lucky that I edited this part to reflect this), however I think it’s still an excellent example of how our brain processes large numbers, not mathematical but emotionally. Or, more specifically, it's a great example of how we scale our affect (psychology jargon for positive and negative emotions) to match different emotional events.

Us humans are an incredibly caring species. We exert great effort and even put ourselves into harm's way to help an individual in need. Some of our most loved stories centre around the heroic acts of otherwise normal people put into extraordinary situations, where they rise to the challenge and save the life of someone in need. This is where our comfort zone is. Rarely do we give, for example, the diplomatic efforts to prevent a genocide, the same emotional weighting.

Adapted from Solvic 2007

Adapted from Solvic 2007 When we’re sat comfortably at home and have time to really think about it, this (Figure 1) is likely the way that we would like human life to be valued. The more people that are at risk the more we care and the more we value saving their lives.

Perhaps we would even logically take it a step further (Figure 2) and think that if the numbers of lives at risk was higher then we would value them more as the loss of life has the potential to destabilise the structure of society itself.

Sadly this is not a post about how we are logical in our reasoning about human suffering. It is instead another post about how our stupid monkey brain drags us down the wrong path of least resistance and how through learning about our own cognitive biases we can gently guide it back on track.

Human affect does not scale linearly

Us humans are a highly impulsive species, we act with our gut far more often than we would like to think we do. Take for example this classic question from Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow:

If you are anything like me your brain is currently screaming “10 pence! 10 pence! It’s 10 pence you moron! Say 10 pence! Go on say 10 pence! God I hate you you piece of shit! Say 10 pence already!! ”.

If so you, like myself and many others, would be wrong.

In this scenario the ball actually costs 5 pence, which is easy to work out if you take your time and think about it (Bat = Ball + £1.00. If Ball is £0.10 then Bat & Ball = £1.10 + £0.10 = £1.20. If Ball is £0.05 then Bat & Ball = £1.05 + £0.05 = £1.10).

However, knowing that the answer is counter-intuitive, and even knowing the answer off by heart itself, I still had to double check this! Why is my brain (and possibly yours) wired against the right answer here? The reason is intuition, or as Kahneman explains it, you give a system one (fast, gut based) response to the question rather than a system two (slow, deliberate, step by step) response.

You can think of the two systems as evolving one after the other, system one was enough to get us through much of human history, system two is all the higher functions we evolved much later.

System one thinks instantaneously, it judges a situation and tries to keep you alive; you hear rustling in the long grass, know that previously this preceded an attack from a lion, so you run. It doesn’t have to be a perfect system, it doesn’t have to get it right all the time (luckily that rustling was just the wind this time), it just has to be good enough.

System two allows us contemplate on an idea and work it through using logic and abstract reasoning. This by no regards means that system one is bad and system two is good, in fact system one is excellent at a task such as judging when to overtake when driving. A system two approach to overtaking would require a pen, paper, a solid understanding of the laws of physics and a few hours or measuring the mass and momentum of each object in the vicinity (stupid system two can't even overtake properly).

System one however has a peculiar manipulative quirk to it when it comes to numbers. This quirk is similar to a concept of Weber’s Law from the field of Psychophysics, whereby we are better at perceiving changes in a low level stimuli (i.e. quiet noise, low light, light weight) than we are when the same change occurs with high level stimulus. For example we can easily tell the difference between a 5 gram and a 10 gram weight but we find it much harder to tell the difference between a 205 gram and a 210 gram weight even though the difference between each weight is the same.

The cognitive psychologist Paul Slovic argues that we make similar cognitive errors when we think about the value of human life. Slovic suggests that we experience psychic numbing as the number of individuals we think about and try to empathise with increases. A paper by Fetherstonhaugh, Slovic, Johnson & Friedrich (1997) demonstrates this concept with two findings.

Firstly, they found that people were less willing to send aid that would save a fixed number of lives (1500 lives) in a Rwandan refugee camp as the size of the camps’ at-risk population was increased between experimental conditions.

Adapted from Solvic 2007

Adapted from Solvic 2007 Secondly, when participants were asked to judge how many lives a $10 million grant would have to save to be worthwhile. The experimenter's found that approximately 9 000 lives would have to be saved if the participants were told 15 000 people were at risk, however 100 000 lives would need to be saved if they were told 290 000 were at risk. With 9 000/15 000 being 60% and 100 000/290 000 being around 33% we can see these diminishing returns in action.

These studies suggest that the way that we value human lives may therefore be more like this (Figure 3), whereby we become numb and more indifferent as the number of individuals at risk increases.

The solution to Psychic Numbing

The difference between saving 87 lives and saving 88 lives has the same value as the first life that you save, however due to inability to fully grasp suffering on this scale it may not feel that way to us.

So how do we proceed when the many are in dire need?

Answer: Draw focus towards the one.

This is exactly what Small et al demonstrated in their 2007 study in which they asked participants to donate to a charity after reading either a statistical narrative (image left) or the narrative of an identifiable individual (image right).

Participants in the study had $5 to donate (earned through a previous experiment). Participants they donated more (an average of around $2.50) when in the identifiable live condition than in the statistical lives condition (an average donation of around $1.15).

We’ve seen the effectiveness of the identifiable lives phenomenon at work in the last few years with the image of Alan Kurdi (picture right) that work the world up to the refugee crises in 2015 and the picture of the child, Omran Daqneesh, after the bombing of Aleppo during the ongoing Syrian civil war.

Job done then. Talk about individuals and we can solve all the problems.

Wait no, stop! That's not the solution, in fact it might make things worse! Damn I wish I’d research this post better before offering a solution. I really hope no one stopped reading after the last paragraph

There was however one additional condition to Small et al’s study and that was the combinations. When the same story was told but this was in the context of the statistics the amount donated averaged around $1.40, a result statistically indistinguishable from just the statistical lives condition. Indicating that adding stats to a story decreases donations

Investigating this further Vastfjall, Peters & Slovic devised a similar experiment with three conditions:

Condition 1: The story of Rokia (as above)

Condition 2: The story of Moussa (a similar but different identifiable lives story)

Condition 3: The stories of Rokia and Moussa together

Again participants were randomly placed in one of the three conditions and were asked how much of their $5 they were willing to donate.

Results indicated that participants parted with less of their money when they were told they would be helping two children in need rather than just one.

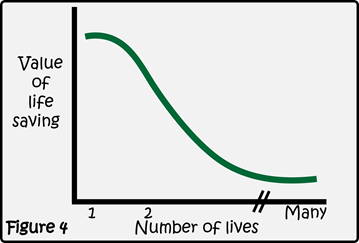

This indicates that the horrifying possibility that this (Figure 4) is how we value lives.

This sadly makes perfect sense when we think in terms of human empathy. We are at our most empathetic when we are thinking in terms of one individual. We put ourselves in their shoes. Have you ever tried to put yourself in the shoes of multiple people at the same time? Sadly it seems to be the case they we evolved a Theory of Mind and not a Theory of Minds, where we care deeply about “the one” but care less so when they are “one of many”.

Ok let’s try this solution business again

But do not despair just yet, what’s that on the horizon riding in to save the day? It’s not, is it…? Yes it is! It’s system two! Remember, from the beginning of the post, the system specifically evolved to deal with logic, reason and abstract thought! It came back for us, even after I mocked it for not being able to effectively drive a car.

Well this is the way I overcome the psychic numbing problem at least, and it works in two parts:

1. The understanding that when I’m exposed a large number that represents a great deal of suffering, empathy is not likely going to occur and encourage me to act. Unless 2. I am able to also see the people behind the data and somehow make the number more real and manageable.

This post is actually about malaria

Yes believe it or not this post actually had a point to it. Today is world malaria day, each year malaria causes around half a million deaths. Below I’ve written you a story, below that I’ve a link that takes you to The Against Malaria Foundation donations page. If you would like to donate please do, I will be matching donations up to £250 over the next week (details at the bottom of the post if you'd like to skip there now). The deal is this you buy a mosquito net and I’ll buy a mosquito net and together we’ll save a life.

You wake up at 7am, pick up your phone, scroll down your Facebook feed and find out that there’s been a plane crash. A Bowing 747. Sure, plane crashes happen every so often but this one is different. This plane happened to have been full of children all under the age of five, 419 children in total. There were no survivors. This stays with you all day, as it would for anyone. People on the news are talking about it all day, it’s the main story, and of course it is, how could it not be? In a passing conversations in the break room at lunchtime a co-worker mentions how horrible it is, and you absolutely agree, yes it truly is a shitty shitty shitty thing to have happened.

Just before you leave work at 5pm you hear that another Bowing 747 full of children has also now crashed. Again there were no survivors. You go to bed later that evening thinking about the images that you saw today and you’re thankful that it wasn’t your child, or a child that you knew, on one of those planes today.

Tomorrow you wake up and to your horror the day plays out exactly the same as the day before, a plane at 7am and another at 5pm, both full of young children, both crash, both no survivors. The next day the same; one plane at 7am and one at 5pm. And the next, 7am, 5pm, over and over again, day after day, week after week, for the rest of the year. After a while the news decides that this is just something that happens now and moves on to news deemed more interesting.

In 2015 there were 214 million cases and 438 000 deaths from malaria, around 306 000 of these deaths were children under 5.

I can’t cope with these numbers, they are too big for me to grasp.

To me the difference between 305 998 and 306 000 children dying is simply not the same as finding out that my neighbours lost their two children last night in a car crash. But it is. It is exactly that.

Illness and death is all a probabilities game, some people never get ill, some people get ill and recover and some get ill and die. The odds however are not evenly spread between every child, for some children the odds are so fucking unfair it would be laughable if it wasn’t so tragic. Many children, by the shittiest of random chance, are born into a world on permanent hard mode.

A mosquito net is an odds shifting device, it makes the odds of survival just a little bit better.

It’s estimated that somewhere around 540 nets distributed to people in an at risk areas for malaria is enough to tip the odds enough so that one person is likely to live when they otherwise would have died.

I think this is an achievable goal for us today. 540 nets for one life seems doable to me.

So often I feel powerless when I watch the news of a tragedy on TV. Today however I want to break a solvable problem down into its parts. We don’t have to look at the huge number today instead let’s focus on one. One life = 540 people giving 1 net each. After that we can focus on the next life.

That net, which you paid for, stands a chance of being the net that stops the mosquito, that carries the malaria, which would have otherwise killed a child. The chain of events here is more complicated than a plane crash but no less as real. Doing this act today is as important and as necessary as you reaching out and stopping a child from boarding the next 7am plane destined to crash.

Random acts of kindness never quite did it for me, today I ask you to join me for a targeted act of kindness.

Donation information

Click here to donate your net here

Post a screenshot of you donation in the comment section below or as a reply to my posts on Facebook or Twitter and I will respond with my matching donation.

The Against Malaria Foundation has been rated by GiveWell, the independent charity evaluator, as the world’s most effective charity for the last 5 years. More information can be found here and through Giving What We Can here

References:

Fetherstonhaugh, D., Slovic, P., Johnson, S., & Friedrich, J. (1997). Insensitivity to the value of human life: A study of psychophysical numbing. Journal of Risk and uncertainty, 14(3), 283-300.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Slovic, P. (2007). If i look at the mass i will never act: Psychic numbingpsychic numbing and genocidegenocide. In Emotions and risky technologies (pp. 37-59). Springer, Dordrecht.

Västfjäll, D., Peters, E., & Slovic, P. (2008). Affect, risk perception and future optimism after the tsunami disaster.