Hello there, people! My holidays in Sweden have been really educational and I have so much I want to share with you. The day we visited the Gustavianum museum my eye caught this:

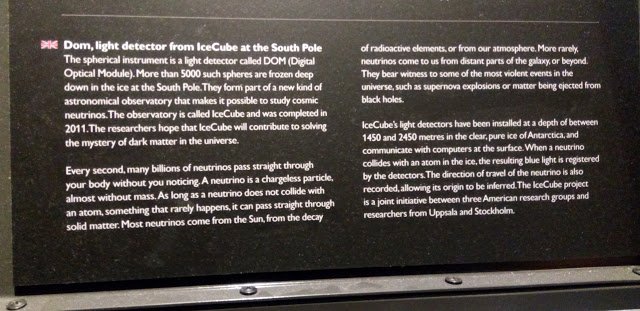

It looks like some kind of lamp but it's not. This weird sphere is called a DOM (Digital Optical Module) and as you can see from the description below these spheres are our 24/7 neutrino spies!

Dear @lemouth, I immediately thought of you when I saw it :)

Apologies for any misunderstandings on the topic, please correct me if I got anything wrong.

Burried deep under the antarctic ice (2.5 kilometers underground), a bunch of 5,160 DOMs take up almost a cubic kilometer and form the "IceCube", the South Pole neutrino observatory. We usually think of observatories as places that look upon the sky, well this one is quite different because it studies the behavior of neutrinos comfortably lying inside the earth's guts. The IceCube is considered a pioneer, as it's the first gigaton neutrino detector in the world and was completed in the end of 2010.

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory was built under a National Science Foundation (NSF) Major Research Equipment and Facilities Construction grant, with assistance from partner funding agencies around the world. The NSF Office of Polar Programs supports the project with a Maintenance and Operations (M&O) grant. The University of Wisconsin–Madison is the lead institution, coordinating data-taking and M&O activities. The international IceCube Collaboration, with more than 40 institutions worldwide, is responsible for the scientific research program. [source]

How does it work?

When neutrinos interact with the ice, secondary particles bearing an electric charge are produced; those particles then emit Cherenkov light because they can travel faster than light through the ice. The Cherenkov light is gathered from the IceCube's sensors, digitized and time stamped in an attempt to form light patterns from the data collected by all the individual DOMs.

Ok, ok, it's a neutrino detector, but what are neutrinos?

Pretty much like electrons, neutrinos are subatomic particles only they carry no electric charge (got it? neutrino-neutral). The lack of charge means no electromagnetic forces can affect them. They were believed to be massless, but scientists have come to think they have some, minimal mass. Their interaction with gravity is minor and they are also affected by weak subatomic forces that lead to radioactive decay (the loss of energy through radiation emission). The extra feature that makes them unique is that they can pass through matter, moreover, they can travel from one edge of the universe to another in the speed of light.

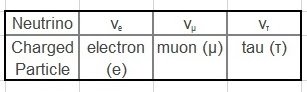

There are three types of them (depending on the charged particle they're related to), I won't go into further analysis here (it's out of my league). A weird fact about them is that they can change from one form to another through a process called neutrino oscillation.

How are they made?

A great number of neutrinos were created around 15 billion years ago. Right after it was created, the universe expanded and cooled without ending, so neutrinos kept on going around. In theory, the total of neutrinos flooding our universe have formed a cosmic background radiation of -271.2 degree Celsius. But there are still more being born every day because of human activities: nuclear power stations, particle accelerators, nuclear bombs, general atmospheric phenomena, and powers beyond our limited control like: births, collisions, and deaths of stars; supernovae offer a great chance for neutrino production.

Why are they important?

Owing to their close to zero interaction with natural forces, we need powerful equipment to detect them in numbers adequate for observation. But they are valuable for scientists because they can reveal useful information. Just like fossils to paleontologists, neutrinos are cosmic fossils revealing the secrets of our creation, the mechanisms that create more complex structures from subatomic particles and many many more!

References

icecube.wisc.edu_detector

icecube.wisc.edu_neutrinos

www.ps.uci.edu_neutrino

simple.wikipedia.org_Neutrino

phys.or_importance-neutrino-physics

minerva.fnal.gov_why-study-neutrinos

All images by @ruth-girl

Thank you for being here today. If you please, feel free to check out my bizarre natural phenomena series, short stories, educational posts or pranks using science.

Special thanks and mentions go to:

Until my next post,

Steem on and keep smiling, people!