We saw a ghost in the corner of the room. Hard black poison. Porcelain fingers and teeth set in six rows. He never slept. He scratched the floor in our dreams. He unlatched the window to let the cool air in so we couldn’t get warm.

Momma said, “no ghosts here. No ghosts since the last exorcism,” but she was superstitious like that. She’d been superstitious ever since her mother smeared blackberry and hemlock on her belly and we came out of her slippery blue and stuck together.

We are Craniopagus conjoined siblings. Conjoined sisters. Siamese twins. That means in the womb our skulls fused together. The nurse tried to smother my smaller sister because she didn’t know any better. My sister ghost-haired and octopus-limbed. She clung to me screaming and screaming until they dragged the nurse away.

It means we dream the same dreams.

It means we saw the same ghost, no matter how many exorcists our mother hired. He dragged his toes against the hardwood floor. His claws clickened and clackened. We clung to each other. His mouth stretched. Heavy. Yawning. Burrowing, big mouth. Big tongue. Crystals studded his tongue. They shredded the roof of his mouth so that the skin hung down in thick strips, and when he breathed the strips fluttered.

Each night he came a little closer to the bed. My sister threw salt down on the floor but he stepped right over it. Clicken. Clacken. The crystals grew heavy in his mouth, and when he unlatched the window they sparkled in darklight. My sister’s snowpowder hair fell off the bed and he bent down and wound it around his wrists to drag himself closer to us.

She said, “This wouldn’t have happened to anyone else.” “Don’t talk like that,” I said, but as always, she was probably right.

“You’re lucky,” the doctors told our mother, “most Craniopagus siblings come out stillborn.”

The doctors told our mother that they could separate us. My sister would die, of course. She’s smaller, the parasitic twin, growth stunted in the womb because I’m greedy. Greedy. But our mother could only shake her head and speak like a gasp.

“No. No.”

I feel sorry for our mother: only 22 years old when she birthed her mutant. I can see her in the hospital bed cradling her new child, that eight limbed with a swelling head. She’s a mousy fern of a girl with a deadbeat dad and a religious father with what looks like God’s strident vengeance spilled into her lap and all she can think is,

“I only bought clothes for one baby.”

She took us home unsplit and fed us and clothed us. Even when her mother, poison alchemist, tried to put arsenic in our pudding, rat-poison in our milk formula. Killing us would have been her special delight. I imagine she wanted to dip us in formaldehyde and nail us to a piece of wood to sell to a curio shop. Or to take revenge on her daughter for not dying in her womb after she drank wormwood tea and ingested parsley and rotten berries and Vitamin C. After she screamed “Out! Out!” like performing an exorcism, after throwing herself down the stairs.

Yet our mother lived. And we lived. Me and my pale rasping sister. We lived.

And we grew. When we were six years old we played marbles in the woods out behind the house, the two of us splayed out in the dirt and our eyes oriented toward the trees, beaded sweat dripping from my cheek to hers. Another neighborhood child, little Thomas, stumbled into our clearing and screamed when he saw us. Tears sprang to his eyes. Hot and wild tears. He started running in circles because he couldn’t find the way out. He tripped over our marbles and fell in the dirt.

My sister laughed. “Don’t do that,” I said. She couldn’t help herself. She laughed and laughed, and this only caused Thomas to scratch

harder at the dirt, to press his hands into his cherub curls and tear out patches. My sister grabbed at his ankle. He screamed louder. I slapped her hand. He scrambled to his feet and ran off into the trees, vine scratches on his face.

“You shouldn’t have done that,” I said.

And though I couldn’t look at her face with our heads fused together, I felt the muscles in my head tense as she smiled.

“It’s fun,” she said, “to be a monster sometime.”

As the ghost crept closer to the bed, my sister wouldn’t let me sleep. She tugged on my hair at the nape of my neck. She scratched my skin.

I grabbed at her stomach. I slapped the side of her face.

“Stop it,” I said, “stop.”

“It’s not a ghost. It’s an incubus.” “

How do you know?” I asked, my head pressed to the sheets, jaw pasted to the wall.

In the periphery of my vision the ghost – incubus – stared at the wall with a blankless stare. His mouth heaved. Underneath his skin his organs glowed. A faint, blue glow. “I read about it,” she said.

She kicked the sheets off the bed.

I turned and tossed in bed, my legs catching chill. But when I brushed up against my sister she’s burning up. Her skin cooking on the surface, skinny little legs flushed red. She panted with her teeth twisting in her mouth.

The incubus could almost reach over and brush her toes with his fingers now. Bend over and snap them off.

“Go away,” I whispered to the incubus. I shivered as the cool air blew through the window. I shivered but my sister’s hot hot hot.

Our teachers told us we could be anyone we wanted. Doctor. Scientist. Stripper. I was always the studious type, but my sister preferred to roll in the grass, blow bubbles into a child’s mouth. I imagined myself trying to perform open-heart surgery with my head twisted to the ceiling and a lopsided blue mask slipping off my nose. I saw my sister welded to me, pregnant and laughing and shaking my surgeon’s knife. In my dreams she released butterflies in the operating room. Wove a spider’s net into my hair.

No, I couldn’t be a doctor. We couldn’t be doctors. We’d read the books about people like us, we’d visited the websites. Chang and Eng Bunker, the conjoined twins from Thailand that performed in P.T. Barnum’s circus. Millie and Christine McCoy, or “The Two-Headed NIghtingale,” conjoined slave children taught to sing and dance for money, stolen away in the night like a toy. Daisy and Violet Hilton, performed in movies like Freaks and Chained for Life. Died alone in their apartment, passing bad blood from one to the other.

They may chain us to the floor or give us a violin or open our mouths and climb inside, but it doesn’t change anything. We can never be anything but Craniopagus conjoined siblings. Conjoined sisters. Siamese twins.

I know this because once my sister fell in love. Some deadhead marijuana mouthed boy who thought he had a savior complex until he met us. He climbed over our fence from a nearby party, drunk and laughing to himself. We were outside on the porch alone, drinking our virgin margaritas that our mother made for us, pursing our sour lips.

“I know you,” he said, “you’re the twins everyone talks about.”

He crawled across the grass in the dew toward us. “You’re the pretty one,” he said to my sister. Of course he would think that of my parasite. She was the glass skinned Ophelia sprung from my head. The girl with the kind of stunted limbs usually only seen in dead anorexics and jellyfish on the bottom of the sea.

“You don’t know what pretty is,” I said.

“Can I have a drink?” he asked my sister, ignoring me.

“It’s virgin,” she said, and for some reason this made both of them laugh.

She held the drink out to him and he spilled it on his chin. It dripped down onto his shirt. They laughed and laughed. Someone called for the boy over the fence. He scrambled up, knocking the glass out of my sister’s hand, and After that night he sent my sister little lace and sugar messages hidden in the trees out in the forest. He tied candied pecans and tiny teddy bears to balloons that floated through our window.

“You look so happy,” our mother said to her.

“She thinks she’s in love,” I said.

My sister touched the lace heart that he’d wedged underneath the door. She stroked her snowpowder hair.

“Let her think that then,” our mother said.

“Fine. I won’t ruin her fantasy then.”

“What’s gotten into you? Why talk to your sister like that?”

And as my mother strained over the kitchen sink, trying to rub the leprous spots off her hand, I thought: because maybe I wanted to be a doctor. Because maybe I wanted to go to sleep for once knowing that my dreams belonged only to me.

“She doesn’t get to fall in love,” I said.

I went back to bed hauling my parasite.

One morning a matted, lean stray cat dropped down the hallway window and came screeching down to our bedroom. We jumped out of bed. My sister caught the cat inbetween her knees. Around its neck we found a string with a letter attached.

Party at my house. Wednesday night. Dress pretty.

She demanded a dress. Silver. Peach ribbons. A pearl necklace. Something that could be zipped up in the back, We had to shop in the child’s section of the department store, with the children and their mother’s staring at us blank-faced and wounded for life. When she picked out her dress we stood together in front of the triple-way mirror. Three monsters. Three lady trolls grimacing and mad.

She tugged at the ends of her hair. She smoothed out the silver dress.

“I could almost…”

“Almost what?”

“Feel like I was real. A real girl.”

“Pretend like I wasn’t here, you mean."

“That’s not it. That’s not it.”

At the party I refused to drink but became drunk anyways, because the boys kept feeding my sister drinks. They smoked her out and my head went sluggish and slow. The boy stroked her hair, told her that he loved her. We went into a back room with my brain crumbling. I ached to fall asleep. It’d been so long since I slept. My sister giggled shy as he led us onto the bed.

“Undress for me,” she said.

“He’ll break you,” I said, laughing as the room spun, “you’re just a little parasite.”

She slapped me on the nose. The cheek. The boy panted as he unbuckled his pants and he stepped out of them with skinny, breakable legs That’s when I noticed the ghost in the corner of the room. Another incubus, I thought. They’re everywhere these days. Becoming immune to the exorcisms, probably. If only we hadn’t exorcised those demons from the bedsheets and the baby crib, the staircase and the water glass. If only our grandma hadn’t rubbed hemlock on my mother’s belly, then maybe the demons wouldn’t be here now.

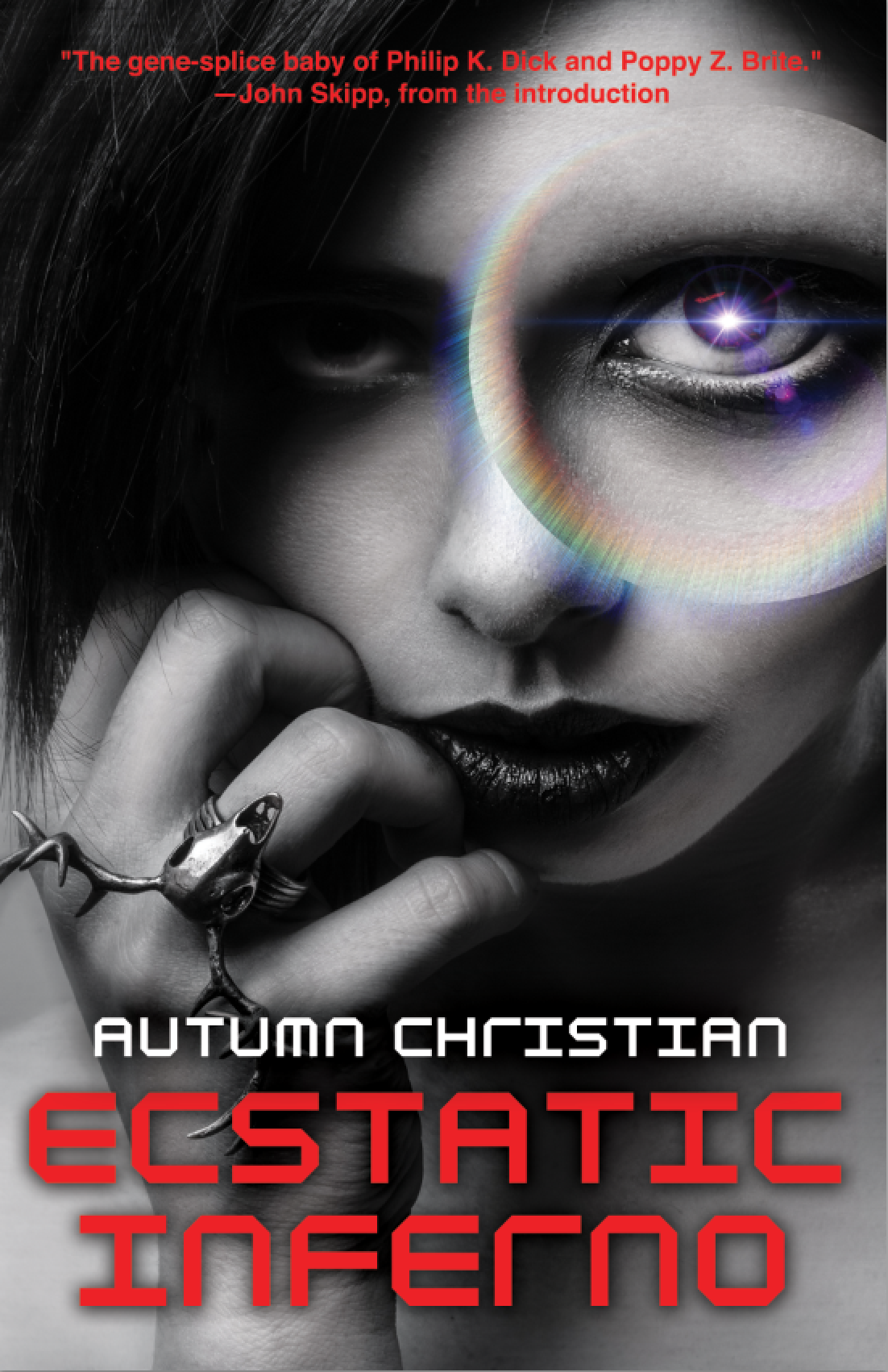

(Note: You can get Ecstatic Inferno here)

The incubus dragged himself closer to the bed. He didn’t have a crystal mouth or a glowing rotten seed for a belly or porcelain skin. He had dirty fingernails and a baseball cap and a t-shirt that smelled of whiskey.

The lover boy lowered himself onto my sister. He wound knots into her hair. They kissed.

“Hey,” I said, all I could manage to say, a whiskey slur. They ignored me. “Hey, does anyone else see that?”

The boy-disguised-as-incubus jumped onto me. He smashed his lips against my jaw and the room tilted on its side. I thought we’d fall off the side of the bed, with his tennis shoes digging into my pelvis and his hunch-limbed spine hitting the sea-side portrait above our heads.

My sister smashed a lamp over his head, spraying me and him with glass. Incubus boy fell off me laughing. Lover boy jumped off my sister wiping at his mouth.

She picked up her torn party dress and we fled. “I didn’t know,” she said as we limped back home. We left behind pieces of silver, tattered pieces of her dress, pieces of glass. By the time we got to the porch our legs were about to break. We quivered with the strain. My sister tried to keep from crying but I felt her tears drip onto my shoulder. So hot they nearly burned through my skin.

We dragged ourselves up the stairs, our mother asleep down the hall.

“Do you know what an incubus does?” my sister said, tugging on my hair.

“Please,” I said, “I just want to sleep.”

“He steals your energy.”

“Please.”

“He fucks you while you sleep.”

We fell into bed and the incubus waited in his usual spot. She choked like she couldn’t breathe.

My heart pounded with the sudden rush of blood from her to me. In the dark my fingers tip-toed over the wasteland of her stomach.

“Him?” I said, “he won’t. We’re more of a monster than he’ll ever be.”

I opened my mouth and hissed. My sister tried to laugh but only rasped. The incubus tapped his toes against the floor. Clicken. Clacken.

In the morning we lay on the couch shell-shocked and half dressed. One sock for four feet. Sweaters with split buttons. Our mother sat cross legged on the carpet with a book of demonology in her lap. A thick, black leather bound tome of a book. She was seeing curses everywhere again: little runic prints on our arms and faces. Maybe she even saw the brand of the incubus like a dark crystal hovering over us.

If only we’d been born real twins, Momma, without this piece of skull sewn between us. Maybe then the incubus wouldn’t have come. Maybe lover boy wouldn’t have brought his friend into the room to rape me while he made love to my pale ectoplasm of a sister. I could have been a doctor.

“I’m sorry, girls,” our mother said, because she could see the scratches on my face where the glass sprayed against me, because she’d found the tattered remains of my sister’s silver dress stuffed into the trashcan.

“Don’t be,” I said, “it’s not like you weren’t expecting it.”

Our mother hummed underneath her breath – some ritual incantation.

“Don’t worry, Momma. It won’t happen again.”

In that moment I could see every place she’d ever been hurt. I saw the broken stem-cells in her belly, the way me and my sister sought each other out in the darkness of her. I saw the scars that tattooed her back where her father struck her with belt-straps, the place where the dog bit her as a child and she screamed and screamed but no one came.

She stretched out on the carpet until her face almost touched the floor, the book underneath her stomach. I reached out for her. I was so tired, everything out of proportion. She seemed a thousand years away.

“It won’t happen again,” I said.

In the night the incubus unlatched the window. He crawled onto the bed. He opened his mouth and the crystals bulged heavy on his tongue.

They glowed fiercer than I ever remembered before. So bright, that tears sprung to my eyes to look at him. He heaved and I shivered. My sister melted down into the sheets. She couldn’t breathe in the heat.

I tried to throw off the sheets and run, but I couldn’t move. The air pressed down with an unbearable heaviness. My lungs welded themselves into my chest. I couldn’t scream for my mother. I couldn’t whisper help. Help me.

The incubus lowered himself onto my sister, puffs of shadow for arms. He ripped my sister’s dress apart with his studded tongue. The shredded skin on the roof of his mouth spilled out on her bare stomach like pale ribbons. I wanted to close my eyes, but I couldn’t.

I’m so sorry, my sister. I’m so sorry. I wanted to give you love but I can’t even turn my head. You can let butterflies into my operating room, sister. You can fall in love. Please, sister.

Sister, please don’t let us disappear. Through the darkness my sister reached out and held my hand. The spell broke. She grabbed the incubus by the throat and pulled him closer.

“Come here,” she whispered to me, her tongue in his mouth, “come here.”

The fever could have burst her brain. My hands sizzled on the back of her hands. We fell backwards into the sheets, hit our head on the baseboards. Kept falling. Spinning, until we were nauseous, his breath distorting space, our heads.

Something. A little something inside of me stirred. I touched the cool place on the back of the incubus’ head. I touched his shadows for arms.

“Come here,” I whispered.

We wrapped our legs around him. Our bare legs touched on his back, hot and cold. We rolled him onto his back, pressed him down. We stretched our spines and rolled our hips. We tossed our hair back.

The incubus squirmed beneath us with his mouth unable to be closed. The crystals grew and grew until his tongue throbbed. We grabbed his arms and wrestled him to the floor, the three of us a worn pile of bodies, our limbs indistinguishable from him to us.

“I told you we were monsters,” I said to the incubus.

I didn’t feel cold anymore.

My sister reached inside his mouth and grabbed his tongue, studded with crystals. He started choking. He heaved and heaved. She reached in with her other hand. Pulled. The incubus collapsed underneath us. My sister opened her hands and his crystal tongue studded thudded to the floor. The dark disappeared. The incubus squirmed underneath us, unable to scream. Rasping, without his crystal tongue.

The heaviness in my chest left me. I could breathe again. We grappled him to the floor.

Maybe our mother would find us in the morning on the floor, melted into the hips of a demon. Three instead of two. Or she’d find us worn down to the bone with the light burning a hole through our ends. Either way we’d be laughing. Laughing.

I didn’t know where I ended and she began. I touched her hips and wondered why I’d gone numb. My head ached in the back, my skull trying to reach around and escape.

I don’t know if we’ll stay together forever like this, torn-fused Kali monster, or if we’ll tear each other apart.

Note: This is an excerpt from my short story collection, Ecstatic Inferno, out from Fungasm Press, which can you get from Amazon.

Follow me on twitter, facebook, or on my website. You can also buy my books here

Stock photo from Pixabay

Self portrait by me canon t51

Some of my other posts you may be interested in:

[Short Story] The Azalea Girl and Her Paingod

[Fictional Memoir] In The Palace of Bones & Champagne

How to Have Fun Writing Again

[Journal] How I Broke Through The Barrier of Dreams // Cognitive and Disassociation Techniques

[Short Story] You Don't Get To Fall In Love