I chose the name storyseeker on Steemit because I, like most of us, am powered by stories.

Stories can be grand; they can teach, inspire, and bring people together.

Stories can be quiet; they can deliver humor, relief, and help us to escape.

There are stories in books and movies, of course, but there are also hundreds of stories that pop up every day in our Facebook and Steemit feeds. We relate to the world through stories.

Stories can be visual.

Art has the potential to help us connect to and think about the world around us. I am often asked about the stories present in my artwork, and I have long been interested in the tales behind the paintings I see in galleries and museums. This is my first official post in an ongoing series about finding inspiration and pursuing meaning in my art.

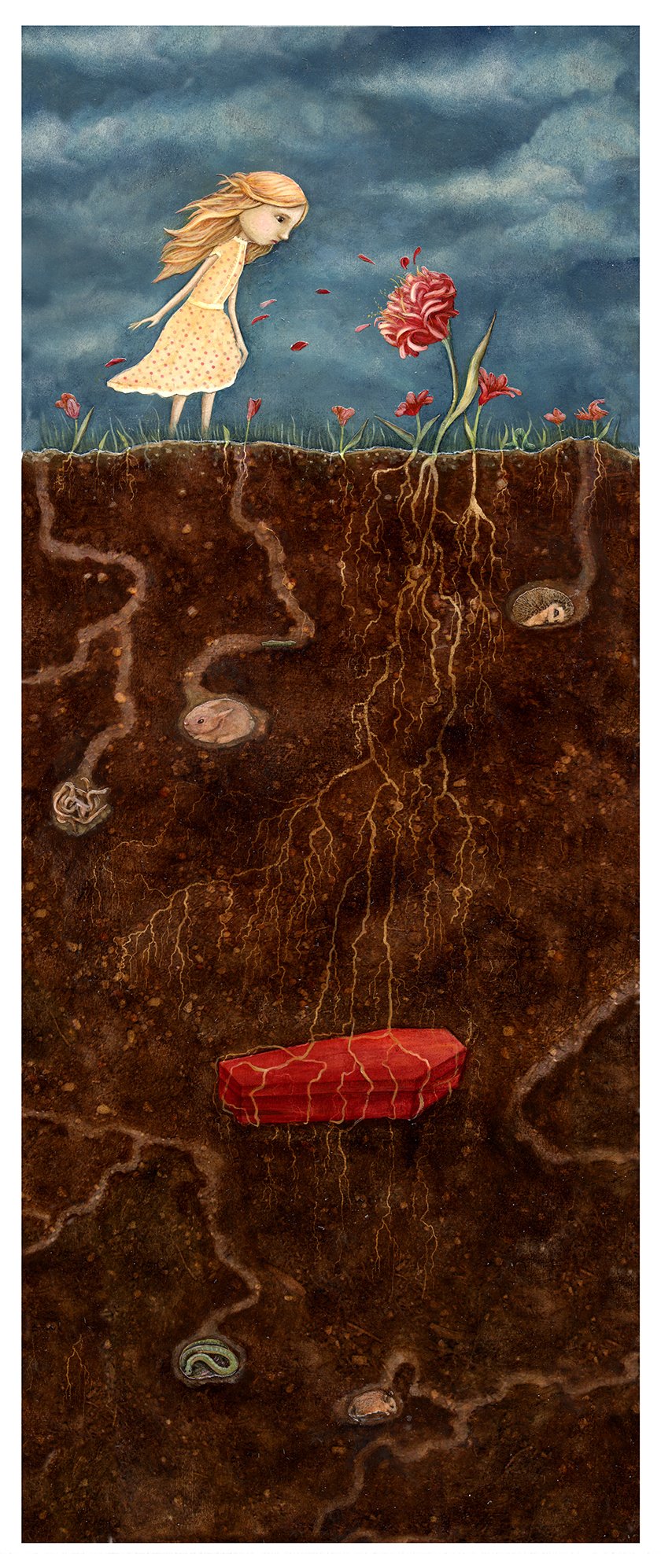

I find it fascinating how some imagery can strike a chord and we aren’t sure why. Garden Secret has been one of those pieces.

Sometimes I get a vision for a piece and start drawing, and other times I sit at my desk and attempt to summon one. When that doesn’t work, I have been known to look to old books and stories. Garden Secret was inspired by a passage I once read in Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen years before executing it. Much of the time, my images are not direct scenes from any one story, but pieces of them. The beauty of making artwork for oneself (as opposed to illustrating one for someone else) is having the flexibility to find your own meaning in its inspiration and the freedom to translate it in your own way.

In the story of The Snow Queen, Gerda, a young girl, seeks her missing friend Kay.

“What, are there no roses here?” cried Gerda; and she ran out into the garden, and examined all the beds, and searched and searched. There was not one to be found. Then she sat down and wept, and her tears fell just on the place where one of the rose-trees had sunk down. The warm tears moistened the earth, and the rose-tree sprouted up at once, as blooming as when it had sunk; and Gerda embraced it and kissed the roses, and thought of the beautiful roses at home, and, with them, of little Kay. “Oh, how I have been detained!” said the little maiden, “I wanted to seek for little Kay. Do you know where he is?” she asked the roses; “do you think he is dead?”

And the roses answered, “No, he is not dead. We have been in the ground where all the dead lie; but Kay is not there.”

I remember reading this passage and thinking about how poetic it was that the flowers knew what lie beneath, presumably because their roots reach deep into the earth. The idea of a flower possessing this knowledge was intriguing.

What do the hyacinths say? “There were three beautiful sisters, fair and delicate. The dress of one was red, of the second blue, and of the third pure white. Hand in hand they danced in the bright moonlight, by the calm lake; but they were human beings, not fairy elves. The sweet fragrance attracted them, and they disappeared in the wood; here the fragrance became stronger. Three coffins, in which lay the three beautiful maidens, glided from the thickest part of the forest across the lake. The fire-flies flew lightly over them, like little floating torches. Do the dancing maidens sleep, or are they dead? The scent of the flower says that they are corpses. The evening bell tolls their knell.”

This eerily beautiful passage offered me a more specific image, a talking flower’s roots reaching deep into the earth and wrapping around a coffin to tell its story.

The original text that inspired my painting was a specific story about three maidens. It offers full rose bushes and hyacinth beds, and describes rotting corpses. My intention was to create a thoughtful image of a concept within the tale. Simplifying the three maidens' corpses to a single coffin and the gardens to a lone flower helps the viewer feel the spirit of the piece without being distracted by the details of the story. This simplified focus is important when creating work that has the potential to impact more people and reach them in individual ways. This is a different process from when I create book illustrations, where I delight in authors’ details, and hide story bits for readers to find. Garden Secret is meant to be seen without the text. It asks questions, it does not offer answers.

I exhibited and sold the original painting at a coffin-themed show in a Los Angeles gallery. This collage-and-acrylic painting has since become one of my most popular posters. Buyers who ask about its inspiration are offered Gerda's tale, but most of them interpret it in their own way. Some see the coffin and mourn the loss of a beloved pet. But many people find comfort in this piece, as they choose to see life and beauty blooming from death. Others see a channeling of the wisdom of those before us. But few will who see it will ever know the story of Gerda, or Kay, or the three dancing maidens - nor will they need it. Sometimes a piece of artwork takes on a life of its own that is more powerful than its origins.

What do you see when you look at this image? If you are a writer or artist, how do you find inspiration?

Note on Technique: For those interested, this piece was created with collage and acrylic paint. Similar to the step-by-step process I posted here, there are bits of collage cut and pasted with gloss medium onto my surface with acrylic paint layered on top. Gerda’s dress is a cut piece of origami paper, and the underground dirt originated with a photograph I took of a bed of soil. I painted my painting on top of these and other collage elements, letting their textures and patterns show through.

Images © Jaime Zollars