Introduction

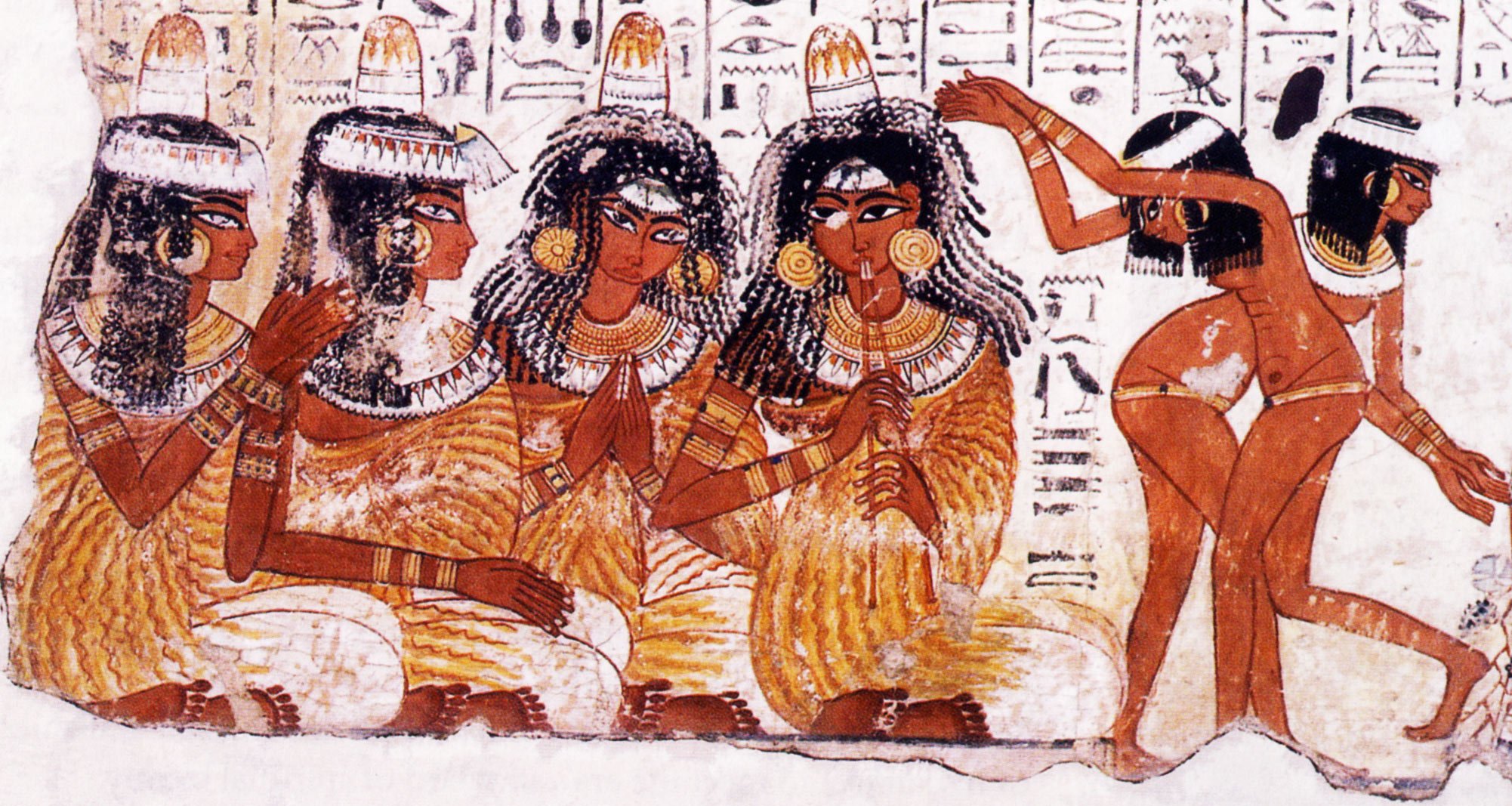

The Ancient Egyptian way of drawing is quite unique to the modern perception: the characteristic depiction of Gods and other protagonists in ritual scenes on temple- and tomb walls are very well known to us and has lead to different interpretations. The song „Walk like an Egyptian“ by The Bangles is just one of the contemporary dealings with that special style of the Ancient Egyptian art.

This typical pose is a result of an artistic phenomenon called „aspective“ – in contrast to the common known „perspective“. The last is used to draw two dimensions to get a clue of a threedimensionsional object. The aspective drawing means in simplified terms, that only certain aspects of an object are depicted, selected by the artist, depending on his/her view, whats important or not.

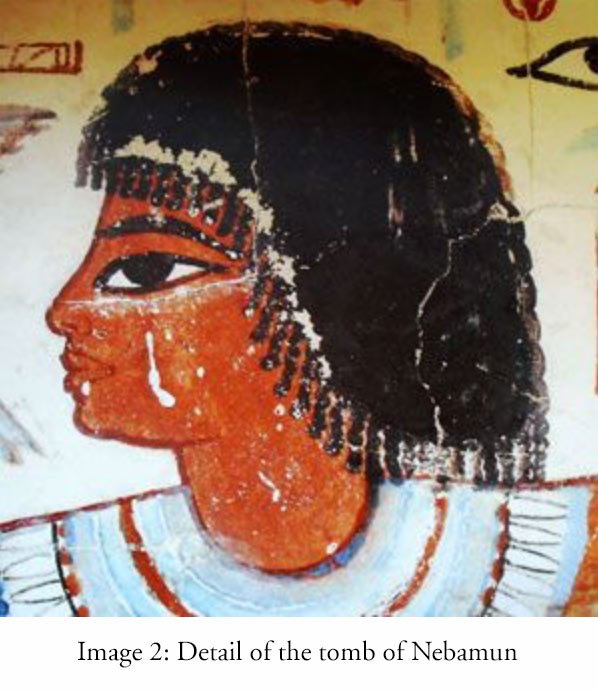

For the Ancient Egyptian art the eyes for instance were more essential then the mouth. That’s why the eye was drawn in frontal view while the head itself was shown in profile view.

A new term derived from some „politically incorrect“ conclusions

The new german term „Aspektive“ was shaped around 1974 by the famous german Egyptologist Emma Brunner-Traut (1911–2008). In her – both celebrated and controversial discussed – book „Frühformen des Erkennens“ (english: Early Forms of Recognition) she was the first who connected Ancient Egyptian art with scientific brain research and came to the conclusion, that the way ancient cultures depicted their everyday life and religious believes, was a result of a „not yet developed“ ability of the brain to reproduce threedimensional objects on a flat medium. In this context she stated, that one could compare the mental state of ancient cultures (Egyptian, Sumerians, Akkadians, Phoenicians and so on) with „mental patients“, „children in their early stage of learning to draw“ or the so called „sunday painters“, which are drawing in non-professional, naive way. (Brunner-Traut 1996, 4; 7ff.) That modern cultures now can draw threedimenional objects could have been caused by an evolutional „change in cognitive-psychic perception" how to gain the shape and nature of an object. (Brunner-Traut 1996, 12). The Ancient Egyptian, so this researcher was convinced, painted what he wanted to be seen, not what was really visible from a certain perspective. The complete object had to be applied to the wall, while a perspective drawn object would naturally hide some parts.

Children and mental patients

After Brunner-Traut (1996, 59) the childish painting is a successive documentation of the process of gaining knowledge and thinking. She stated, that this ability is available to the child in a very early stage, but the ability for perspective drawing must be learned through long and hard exercising.

But what’s even more interesting: a list was published 1962 by the psychiatrist Helmut Rennert, that Brunner-Traut used as a reference for describing the egyptian „state of mind“: Amongst other things Rennert found out, that mentally ill people (including shizophrenics, neurotics and also drug addicts with brain damages):

- have a lack of perspective in their drawings

- tend to combine human and animal body parts

- have an emphasized interest on the „eye“ (of humans/animals)

(see reference in: Brunner-Traut 1996, 63f.).

The misconception: something important was not considered!

The given example from that child’s drawing might be comparable with the drawings of the egyptians. But especially the coincidence with Rennert's list is intriguing. So Brunner-Trauts conclusions are not surprising.

But we are talking here about a culture that was not just „creative“ in decorating their tombs and temples, acting like children that are discovering their world around them or like shizophrenic patients with a perceptual disorder. They used pictures mainly for magical purposes! Much has been already written about the ancient mythology, the religious beliefs and performed rituals (see Assmann 2002). As we now know, not a single object was drawn randomly on a wall. Also it was not just an artistic approach! (Almost) every piece of a composition was part of a complex system of magical actions. The aesthetic in drawings were guided by Ma’at – the principle of order in contrast to chaos. They never painted their walls with things they wanted to avoid! No failure or drama is shown on that theater-like stages where the Ancient Egyptians were buried.

So, the aspective drawing is a natural consequence of the desire to show what they wanted to be existent in eternity. That’s why we see things on their their creative compositions that you can’t percept normally by just looking at an object. The Ancient Egyptians projected their wishes to walls, stelae and other mediums in a very conscious way. To be working properly a magical act required a precise fixing of the information on a medium (see as an example: von Lieven 2002, 56). This is one of the main reasons of the „aspective“ paintings. The „eye“ meant safety and protection (Müller-Winkler 1986) - so it had to be shown completely. A „half“ eye – like in a perspective drawing – would cause the loss of safety and protection in the afterlife: a terrible idea for the Ancient Egyptians.

Summary and conclusion

The idea of an „early stage“ in development of mental abilities was of course a „hot iron“ Brunner-Traut touched (see quote above). She was clear about it when she published her research. She knew that her opinion would cause a yelp in the scientific world.

The theories of Brunner-Traut could be proven wrong by extending the research to the basic philosophy of the Ancient Egyptians. Drawings of mixed human-animal deities for example were expressions of their religious conviction, that every part had a special power and in that combination the power would be more effective.

But while Brunner-Trauts ideas can be called „political incorrect“ today, she presented her research in a very guardedly way and never left a doubt about her appreciation to the cultural heritage she was writing about. She honored and respected the Ancient Egyptians. So she is a best-practice example for courageous scientific research. She was brave enough to discover unknown territory and paved the path for further interdisciplinary research. This was something that the academic compartment of Egyptology must learn: to come along with other disciplines, modern approaches and even controversial ideas. To understand past cultures in their entirety we must not only look at objects that we pull out of the sands. We have to work together with life sciences, anthropologists, experts of cognitive psychology and so on. All this will sharpen the lense for our perspective on the motives of our ancestors. Maybe one day we must completely correct our view on the Ancient Egyptians, who might be more advanced than we imagine right now. Who knows…

Bibliography

• Assmann, Jan (ed.), Ägyptische Mysterien?, Munich 2002.

• Brunner-Traut, Emma, Aspektive und die historische Wandlung der Wahrnehmungsweise, Stuttgart 1974.

• Brunner-Traut, Emma, Frühformen des Erkennens: Aspektive im Alten Ägypten, Darmstadt 1996 (3rd edition).

• Rennert, Helmut, Die Merkmale schizophrener Bildnerei, Jena 1962. (cited after Brunner-Traut 1996, 63 f.)

• von Lieven, Alexandra, Kosmographie und Priesterwissenschaft, in: Assmann, Jan (ed.), Ägyptische Mysterien?, Munich 2002, 47–58.

• Müller-Winkler, Claudia, in: Lexikon der Ägyptologie VI, Wiesbaden 1986, Sp. 824–826, s.v. Udjat-Auge.

Images Sources

Image 1: Source

Image 2: Source

Image 3: Scan of Brunner-Traut, Emma, Frühformen des Erkennens: Aspektive im Alten Ägypten, Darmstadt 1996 (3rd edition), image 36, page 45.

Image 4: Source