Imagine a couple, arguing for the umpteenth time about who did what, or who forgot to do something. Maybe you were in an argument like this yourself recently. Don't think of that one. Also, don't think of the ones that have valid, life-changing reasons fueling them. Scour your memory for a third-party perspective to a really dumb argument. If you can, trace the argument back to its base premise.

What you'll often find is that both parties claim knowledge of a random detail in a memory. This random detail was a marker that triggered other details in the memory. Somehow, in conversation, the specifics of this memory marker were elucidated by one party, and the other party objected. The marker did not match their version of the story. An argument ensues.

What's the argument really about? Certainly not the detail. No, it's about the absolute trust people put into certain memories. It's taken as a personal attack. A judge of character. You are a liar.

Maybe in the more reflective stages of the conflict, one party briefly wonders why the other party would even bother to lie about something so trivial. It's at this stage that their memory of the detail is simply challenged. But the accused won't agree. 'No,' they say, 'I remember clearly. Your memory is wrong.'

And unless the argument is between the most hard-headed people on earth, this usually helps diffuse it. 'They just don't remember correctly,' your brain decides. And all the little details fall into place again. Your brain is satisfied with the consistency it has created.

What is happening behind the scenes?

Confabulation is today's word of the day. It's how your memory actually works, and it'll probably throw many of you for a loop.

But first let's start with what your brain isn't. Your brain is not a hard drive recording video from a camera. Far from it. But many people treat memory as their own personal video evidence. Memory is a storyteller that takes a small collection of markers and fills the rest of the story in. Oftentimes certain markers are stronger. Perhaps they emphasize our good character traits, so they are embellished. Other markers are weaker. They don't really emphasize anything important to us or perhaps they emphasize our flaws. These are downplayed.

Sometimes the reverse of this happens if the person is in a depressed state, but either way, our memories are not exact. Our brains put a twist on them to suit a narrative.

It's not a question of lying. It's a question of brains recreating stories from limited amounts of stored information. It is encoding loss.

Wild claim there, buddy. Where's the proof?

Well, probably the most enlightening experiments ever done with regard to how the brain works are done on split-brain patients. Some of these experiments will shed light on this question.

The background of these types of experiments is that in order to prevent debilitating seizures, many patients used to have the two halves of their brain separated by severing the corpus callosum (now this surgery is very uncommon since the exact origination point of most of these types of seizures can be found with ECoG and eliminated with more precision). These people are almost complete normal with one key difference. The two halves of their brain can disagree, and often do.

Since speech is performed in the left half of the brain, only one side can speak. However, since both halves control an eye an ear and an arm, it's still possible to communicate with each half separately.

There are many fascinating experiments that have been done in this realm that call all sorts of conventional beliefs we hold about ourselves into question, but I'll be focusing on one specific set.

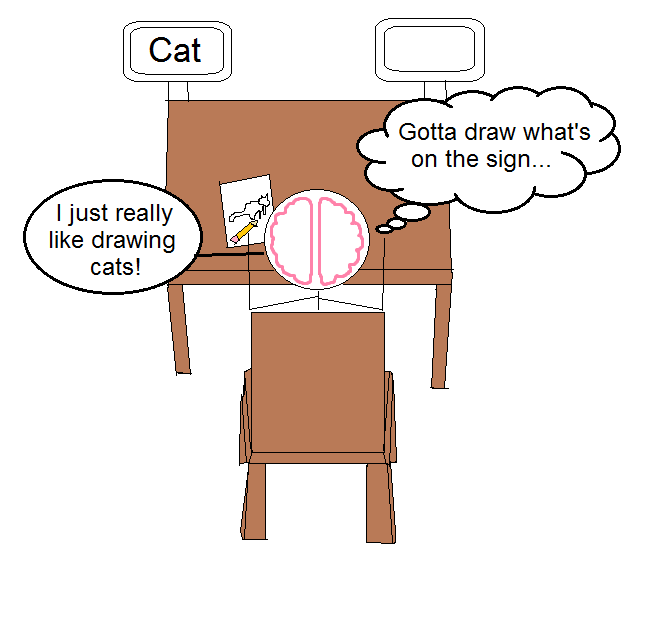

The set of experiments was tried in various ways, but the main premise is that a task was given to the silent right half of the brain by showing it only in their left visual field. Since the left half of the brain cannot see it, it doesn't understand why the right half of the brain is doing a task.

One experiment asked the right half of the brain to draw various objects. Afterward, the left half of the brain was asked why he drew the objects. Instead of answering, 'I don't know,' the left half of the brain confabulated. It came up with answers such as, 'I just like drawing these kinds of things.'

The left half of the brain needed a consistent explanation. It didn't matter if it was right.

This experiment shows that the brain fills in the details of a story to which it has no marker arbitrarily, and then confidently uses those in-the-moment, arbitrary details as fact.

So, what's the take away?

Rather than being frightening, knowing that is how memory works is actually empowering. Taking advantage of this knowledge can let you memorize chunks of information much quicker, but more than that, it dissipates stupid arguments.

If there's a good chance one or both of you completely confabulated the controversial detail (because that's just how brains remember things), then it's a bit silly to take it as a judgement of your character.