Dear Reader

In this following series of posts we are covering the Later Stone Age of South Africa, I highly encourage you to please read the Introduction, Historical Background, Advances in Later Stone Age, Climatic conditions of the LSA in South Africa, Elements characteristic of the Later Stone Age, The Later Stone Age sequence, Early Later Stone Age: Robberg assemblages, Robberg Subsistence Economy, The Oakhurst, including Albany and Lockshoek non-microlithic assemblages, Wilton assemblages and Hunter-gatherers' way of life:Introduction posts to this series to bring you update to date with the information and terminology we have covered so far.

Hunter-gatherers way of life during the Later Stone Age: Ethnographical Evidence

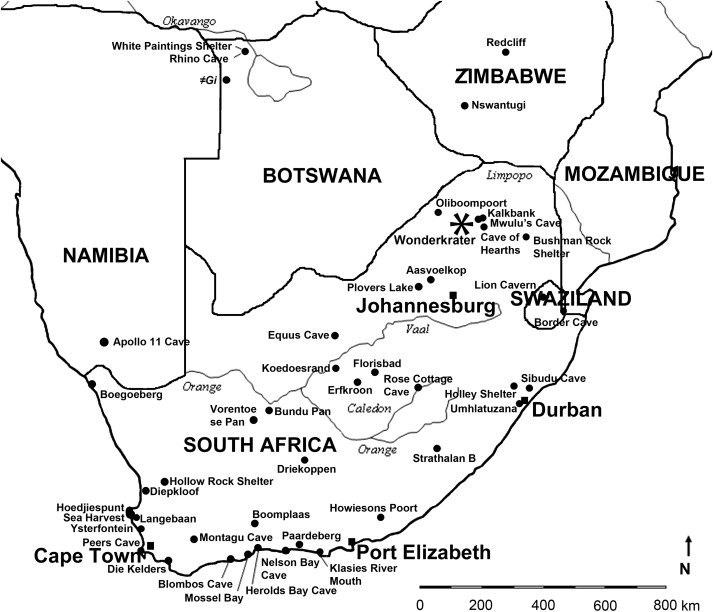

In 1930 Schapera made a synthesis of all the relevant ethnographic material on the Khoisan recorded by early travellers and European government administrators. Since then various detailed and scientific regional studies have been carried out on those various groups in the Kalihari who still depend on a subsistence hunter-gatherer economy. Some of the most important observations that have emerged from these studies are summarised below. Archaeological evidence indicates, to some extent, the time duration and geographic spread of similar subsistence practices amongst the prehistoric San.

- The San hunter-gatherers' extensive knowledge of phenomena such as different land-patterns (with diverse plant and animal food resources) is vital for their survival.Hunter-gatherer groups have rights to resources available within territories ranging from 3000 to 12 000 square kilometers. The size of each territory depends on sources of water and the availability of major plant food resources. The daily and seasonal movements of hunter-gatherer groups are related to the availability of plant food, water and game.

- Water sources include permanent waterholes, standing water during rainy seasons, water sucked through hollow tubes from natural water caches in hollow trees and from sand pits dug in river beds. Another major source of water comes from fruits, roots and bulbs of moisture-storing plants. The stomach fuild of animals killed during hunting is used when no other water is available. Some territories include more permanent water sources than others. The San have rights to a desert area (which includes half of the Kalihari Reserve) with very little permanent water resources; they consequently rely on alternative water sources in a generally larger territory. For a large part of the year they are almost exclusively dependent on the storage organs of plants for their water requirements.

- The availability of basic resources (ie plant and animal foods, shelter and firewood) varies between the major biomes in southern Africa. In the Basutoland, Karoo and Cape ecozones geophytes with carbohydrate-rich underground storage organs are major plant foods. Fruits and their seeds provide the bulk of plant foods within the Transvaalian savanna vegetation. Tubers, tsamma melon, nuts and berries are important in the Kalahari ecozone (Mitchell 1997:374).

- The availability of a wide variety of food is recognised within a specific area. However, the most impotant criteria used in relying on preferred foods as staples are abundance over a long period; the relative ease with which they can be gathered; and lastly taste and nutrition. A regional adaptation to a preferred set of staples is an important adaptation strategy. In some areas hunter-gatherer groups rely heavily on easily available plant food for protein and fat requirements. Examples of such plant foods are Manketti or Mongongo nuts (Schinziophyton rautanenii), marula nuts (Sclerocarya birrea), marama bean (Tylosema esculenta), of which the enormous underground tuber is also a major source of water, and beans (Bauhinia sp.). Plants mainly used for their moisture storage abilities are tsamma melons (Citrullus lanatus), gemsbok cucumbers(Acanthosicyos naudiniana) and a tuber (Raphionacme burkei) known as bi to the San. The natural storage organs of plants such as roots, corms, bulbs, seeds and nuts are mostly used as staple foods on the account of their prolonged availability and the fact that they have good preservation qualities. Food is seldom stored during times of abundance.

- Although meat is regarded as a major food, t is not abundant and the San rely predominantly on plant foods to meet their food requirements. Meat from large animals provides the main source of meat by weight. The smaller game provides less meat, but this source tends to be available throughout the year. The gemsbok (Oryx gazella) and eland (Taurotragus oryx) (eland are now very scarce) are considered to be the most preferred and important species.

- Large game is always shared within the band. Small game, such as the young of animals, hares, tortoises, and similar catches snared by the men or children (and sometimes collected by woman while gathering) is used by a particular household. The season also determines the amount of meat available.

- Poison from various sources is used on arrowheads. These include the poison sacs of some snakes, the head and tail of scorpions, spiders and specific larvae grubs and, in some areas, also plant substances. Some groups hunt mainly in summer with bow and poisoned arrows because poison grubs are then readily available; after four to six months the poison is either unavailable or losing its strength. Springhare hooks of Grewia wood are used to extricate springhare from their burrows. Game pits, covered with grass,are sometimes used to trap game. In the winter months snaring or trapping is used more often because, in summer, moisture may weaken the twine used to make snares.

- A gender-based division of labour. Men hunt and undertake other tasks such as tool manufacture and maintance, the preparation of skins and manufacture of articles from skins (Deacon & Deacon 1999:155-161). Women are traditionally the gatherers of veld food, small animals such as tortoises, insects, etcetera, shellfish and wood. Women never hunt, although an old woman may be the owner of some arrow heads.According to the San system of ownership, the owner of the arrow that killed the animal is the owner of the meat and initially receives the most important part of the animal killed during the hunt. In the end everybody in the band receives some share of the hunt through redistribution of the meat. Men may also gather on their return trip if hunting was unsuccessful. Women play an important role in the procurement of food since modern hunter-gatherers depend heavily on the reliable veld foods as their primary food source. Most underground plant foods have high water and carbohydrate content, but low protein values and have to be supplemented by protein sources such as meat and plant foods with a high protein content.

- Egalitarianism, as already pointed out, forms an integral part of the organisation of the San. All band members are involved in decision-making, and although elderly men and woman (plus skilled hunters and healers) are held in high regard, everybody is equal and there are no formal chief or rulers.

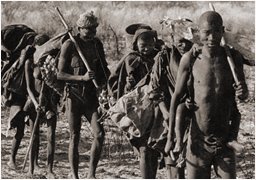

- Because they have to be mobile, the San limit their possessions to the amount that can be carried as they schedule their movements to coincide with seasonally available food. The digging stick and skin kaross, carrying nets, skin bags and ostrich eggshell water containers are among the most important possessions of the women. The hunting kit of the men is more diverse. Several hunting items are carried in a quiver and may include a bow and arrows, arrow heads and poison, knives, and flint-and -steel fire kit (Deacon & Deacon 1999:158-159). Springhare hooks and snaring equipment also form part of the hunting kit.

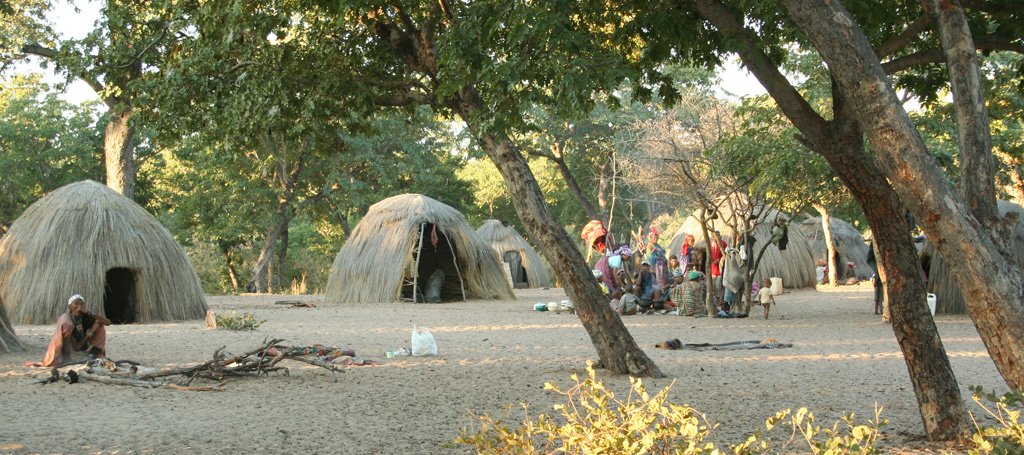

- Small windbreaks or flimsy shelters are built during fine weather when they only intend to use them for a short period of time, for example during hunting trips. Their huts are contructed from poles. Roots are used to tie these poles together to form the framework of a hut-a hut is about 2 meters in diameter and 2 meters high. This framework is covered with tall grasses of a variety of species that do not burn easily. The huts are arranged in a circle, usually with a few trees in the middle for shade and group social activities. A hut for each nuclear family is usually built by the woman, with camp size varying widely from 1 hut to about 20. Although there is a generally acknowledged nucleus of permanent territorial residents, the composition of camps is very flexible and may change frequently as individuals or families move and visit between bands. Huts are used for sleeping, storage and, frequently, for protection against rain and cold.

Hearths play an important role in "demarcating" the private area of each hut and are situated outside the hut, near the enterance. Among the !Kung the man sits on the right and the woman on the left side (the observer facing the entrance into the shelter) of the hearth. The hearth fulfills a social function because most of the nuclear family's activities are centred around it.

- A system of periodic aggregation and dispersal, or a public and a private phase, is found among modern San bands. This system resolves the problem of balancing efficient use of the environment (often best achieved in a small group) with social requirements (often best acheived in a large group) (Wadley 1993: Mitchell 1997). The availability of food and water sources influences how this system works in practice. Simple subsistence activities are undertaken and ritual and travel minimised when the band disperses into smaller family units. The public phase (during which kin-related households congregate) is characterised by formal behaviour and social and ritual activities such as marriage brokering, socialising, large-scale manufacture of goods and reciprocal gift exchange (hxaro), initiation and sometimes puberty rites.

- Hxaro ties, through which a reciprocal exchange of gifts through a network of partnerships takes place, are renewed or created during the public phase. Almost anything except food is given as a gift. Formalised gift exchange is known as hxaro by the Ju/hoansi or !Kung and //ai by the Nharo. It was apparently important in /Xam social relations as well. This system reduces risk and serves as an insurance against ecological disaster. Through Hxaro parterships, information about people and resources is distributed over distances of 200 km or more. Exchange is intensified during drought and other stressed conditions and when people seek marriage partners for their children.Hxaro partners exchange gifts, but can also be given rights to gather plant foods or water in the territories where they have ties.

Images are link to their sources in their description and references are stated within the text.

Thank you for reading

Thank you @foundation for this amazing SteemSTEM gif