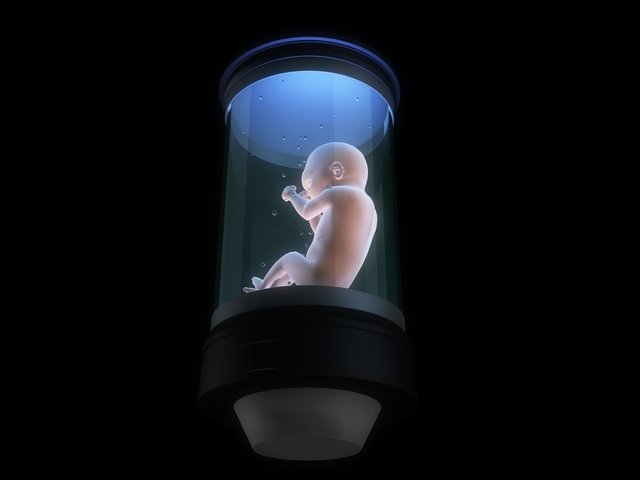

WHAT IT COULD MEAN TO HAVE ARTIFICIAL WOMBS

(Image from futuretimeline.net)

It is an abiding characteristic of transhumanists to be simultaneously in admiration for the human body, impressed with what evolution achieved, while also considering the body as very much work in progress that needs fixing.

One aspect of life that science and technology have made impressive strides in is pregnancy and birth. Today, thanks to modern medicine, surgical techniques, biotechnologies like IVF and social services like surrogate motherhood, people who in previous years would have died in infancy, childbirth, or would never have been born at all are able to live a full life.

There is still plenty more we could do to improve our chances of delivering healthy, happy babies. One conceptual technology that would seem obviously to improve the drive to create the next generation would be artificial wombs. We already have neonatal intensive care units that can keep alive babies born as early as twenty weeks (half their final gestational stage). These machines breathe for the tiny infants, coat their lungs with replacement amniotic fluid and pump them full of food and drugs through surrogate umbilical cords. But these machines are far from perfect, and so more than half of these infants will suffer some kind of physical and mental disability. Obviously that is not good enough, and we should strive to improve neonatal care technologies in order to lessen these risks. As we find ways to improve such machines, we could very likely push back the time when a baby born prematurely can survive outside of the womb, until eventually it is possible to provide a protective environment from the moment of conception onwards. A neonatal care unit that could look after a developing human from fertilized egg all the way to birth-ready infant would by definition be an artificial womb.

(Neonatal care unit. Image from basildonandthurrock.nhs.uk)

Combined with other medical technologies like cloning, the artificial womb would enable people to become families who are currently unable to do so due to medical or biological reasons, the most obvious latter example being gay couples (of course gay couples can and do become adoptive families, but there are conceivable biotechnologies that would enable them to become families in which both parent invests his and his or her and her genes).

Moreover, pregnancy is pretty cumbersome. It entails having to put up with a gross, bulging tummy. It means morning sickness, and back pain is a common ailment. It entails having a stranger take up occupancy inside your body, growing like a tumor before being pushed out of a tiny orifice along with much pain and plenty of gross body fluids spilled everywhere. No wonder the concept of the artificial womb sounds so ideal to a lot of people.

But, I think we should exercise caution and look closely at why we want to adopt such a thing. Of course there are good reasons to pursue such a technological marvel. As I said before, we should strive to improve neonatal care units so that they can provide care for growing babies that otherwise would die or suffer defects. But to want to adopt this technology just because you deem pregnancy an inconvenience to your lifestyle? Is that such a good idea?

THE INDIVIDUALISTIC SOCIETY

Ours is an individualistic society, where cultural norms are designed to emphasize a distinction of the self from others, all the better for being raised in a society that favors competition and mobility. We see this attitude reflected in our idea of what constitutes the ultimate status symbol: A large house on a huge estate, preferably with a large fence and gate to keep out uninvited guests. In other words, success in our culture is defined by how much space you can impose between yourself and other people.

Social media connects us to more people than was ever possible before, but it also serves to separate us, enabling us to communicate via the screen. We are, as the title of a book by Sherry Turkle put it, ‘alone together’. That book, by the way, contains many case studies of people neglecting the people around them in physical space- often their own family- in favor of the huge network of virtual ‘friends’ they have accumulated through services like Facebook. One example that springs to mind is the mother who picked her children up from school but who barely acknowledged their presence, so engrossed was she in twitter.

One way to expose flaws in a culture is to examine another where things are done differently. There are other cultures where survival depends greatly on mutual economic dependence- sharing what you have with others. In such societies we find greater cooperation between people as well as a great deal of tactile contact.

HOW THEY DO IT

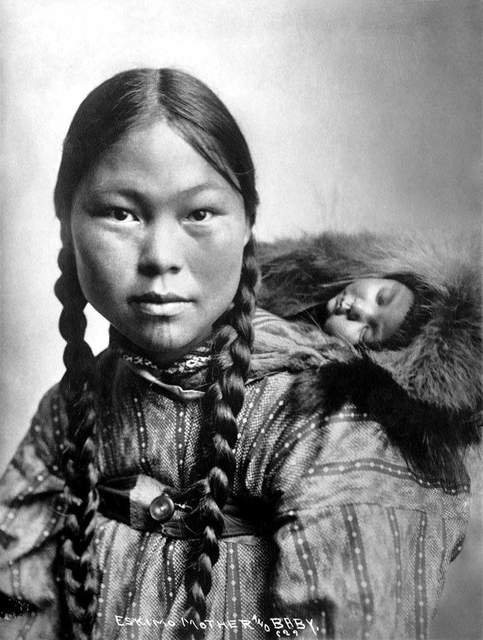

Consider the traditional clothing of the Netsilik Eskimo and the bond it creates between mother and infant. The Netsilik wears a fur parker known as an ‘Attigi’. The infant is placed in the back of the attigi, assuming a sitting posture with its legs around Mother’s waist. A slash is worn around the outside of the attigi, serving as a sling to support the infant. Apart from a tiny nappy made from caribou skins, the infant is naked and spends the majority of its days in close physical contact with its mother’s body.

(image from nativi.altervista.org)

The attigi keeps mother and baby in close physical contact and it is via skin to skin communication that the mother is alerted to her child’s needs, which are satisfied immediately. Netsilik infants seldom cry.

Now you might argue that Netsiliks favor so much bodily contact not because they are a more cooperative, touchy-feely people but because they live in a very cold place, and shared bodily warmth is a great and practical way of keeping warm. But even if that were the case, there are other cultures in much warmer climates who adopt similar practices, and get similar results: Happy babies who seldom cry.

For example, another highly tactile tribe are the !Kung bushman of Botswana in Southwest Africa. Dr. Patricia Draper noted how they lived in bands of 30 people and that they really like being close together. Whether resting or working, they prefer to be in physical contact with each other, arms brushing, leaning against one another. Here, too, infants are seldom separate from mother and, as Dr. M.J Konner wrote, “when not in the sling they are passed hand to hand around a fire for similar interactions with one child or adult after another. They are kissed on their faces, bellies, genitals, sung to, bounced…even addressed at length in conventional tones long before they can understand words”.

(Image from Pinterest.com)

It may seem disturbing to us that they kiss their babies’ genitals, since this part of the body is taboo to us. But we should not interpret this behaviour as sexual. It is more of a physical demonstration of platonic love between fellow tribe members upon whose loyalty and cooperation the individual depends utterly.

Now let us contrast the clothing that mother and baby wear in these cultures- clothing that is designed to keep the two on bodily contact- with the clothes Western families wear.

THE WESTERN WAY

Far from being a convenient way to bind a child to its mother, clothes for us serve to separate mother and child. It is typical for both mother and child to be clad in their own garments during feeding, such that the only contact the infant has is with the breast and maybe some hand -stroking. Actually, given that bottlefeeding is the rule in America, a baby in this culture receives the absolute bare minimum of reciprocal tactile stimulation. When not being fed, the Western infant spends most of its waking hours and all of its sleeping hours separate from others.

Indeed, this separation of mother from child begins straight after birth, as this excerpt from the book ‘Touching: the human importance of skin’ by Ashley Montague makes clear.

“The moment it is born, the cord is cut or clamped, the child is exhibited to its mother, and then it is taken away by a nurse to a babyroom called the nursery…Here it is weighed, measured, its physical and any other traits recorded, a number is put around its wrist, and it is then put in a crib to howl away to its heart’s discontent”.

(Image from sheknows.com)

Of course they howl. This is not what babies want. A baby is most comfortable when experiencing conditions that reproduce those of the womb. The one place in the external world that gets closest to such conditions is a mother’s embrace where baby is enfolded in her arms at her bosom. You can see this need in mammals and especially primates: Infant monkeys and apes are all but inseparable from their mothers.

With the artificial womb we could extend this separation of mother and infant right through the entire gestational period. I am sure that would be convenient. Working mothers would not need any maternity leave, having delegated the responsibility for gestating their son or daughter to machines. Arguably I am being unreasonable in using such a cold term as ‘machine’ here. It could be that artificial wombs function so well that the fetus could never tell, let alone care, that it was not in a natural womb. But there has got to be a difference for the mother, not having that physical connection between herself and her baby, cared for inside her own body. Not that I am implying that parents whose children were not grown inside the mother’s body cannot care. Adoptive parents prove that notion is wrong. What I am saying is that it could very well be a great pity for women to miss out on the experience of pregnancy- surely one of the miracles of nature- for no reason other than its inconvenience for their working lifestyles and its antipathy to the highly individualistic society we live in, which seems to be striving to create more and more separation between us.