My grandfather wore a patched shirt but was known as a village aristocrat because he drank "real, expensive tea". This was not fruit tea, of the kind sold in pressed bars, nor country brew made of dried apples and pears, nor raspberry, bird-cherry or lime-blossom tea (which is revered in the countryside, but should never be called tea). He drank real, fragrant tea that came in tinfoil packets.

My grandfather was a connoisseur and an avid tea-drinker. His log house that smelled of honey, apples, pine shavings and dried herbs summer and winter welcomed one and all. The penny-pinching village men would deride grandfather for throwing his money around, saying, "Pavel Matveyevich spends every copper he has on tea." But they were always glad to find an excuse to drop in.

The most fascinating dinner-table conversation I ever heard took place around my grandfather's samovar. Everyone sipped their tea solemnly from saucers according to the village custom, and the talk was just as solemn and unhurried. They drank cup after cup, often disregarding the village tradition of retiring early, and sat up talking till midnight. There was the latest local news, or talk of where a traveller had been and what he had seen. I would sit on the bench near the wall in back. Towards midnight I would imagine that the table and the steaming samovar on it had turned into a ship that was ready to sail out of the window. Sometimes they sang the old songs. I heard my grandfather tell the story of tea often at this table.

His grandson has had tea in many parts of the world: in Russian tearooms along the highways, in Uzbek tearooms, in Vietnam, where no conversation can begin without a cup of tea, at campfires in Siberia, in the tundra, where a day's journey is measured in "tea stops", and at home. I have often recalled my grandfather saying: "If you're tired, have some tea", "If you're hot, have some tea", "If you want to warm up, have some tea".

On a visit to a tea plantation not long ago I sat at the best of tea tables with people who were experts on the subject of tea and tea-drinking. Once again, I recalled my grandfather's samovar. Although he could have taken part in the conversation on a par with the others, there was much he did not know about tea.

Tea comes from China. According to legend, shepherds noted that their sheep became frisky after eating tea leaves and so were the first to taste the brew that was to become one of the world's chief beverages.

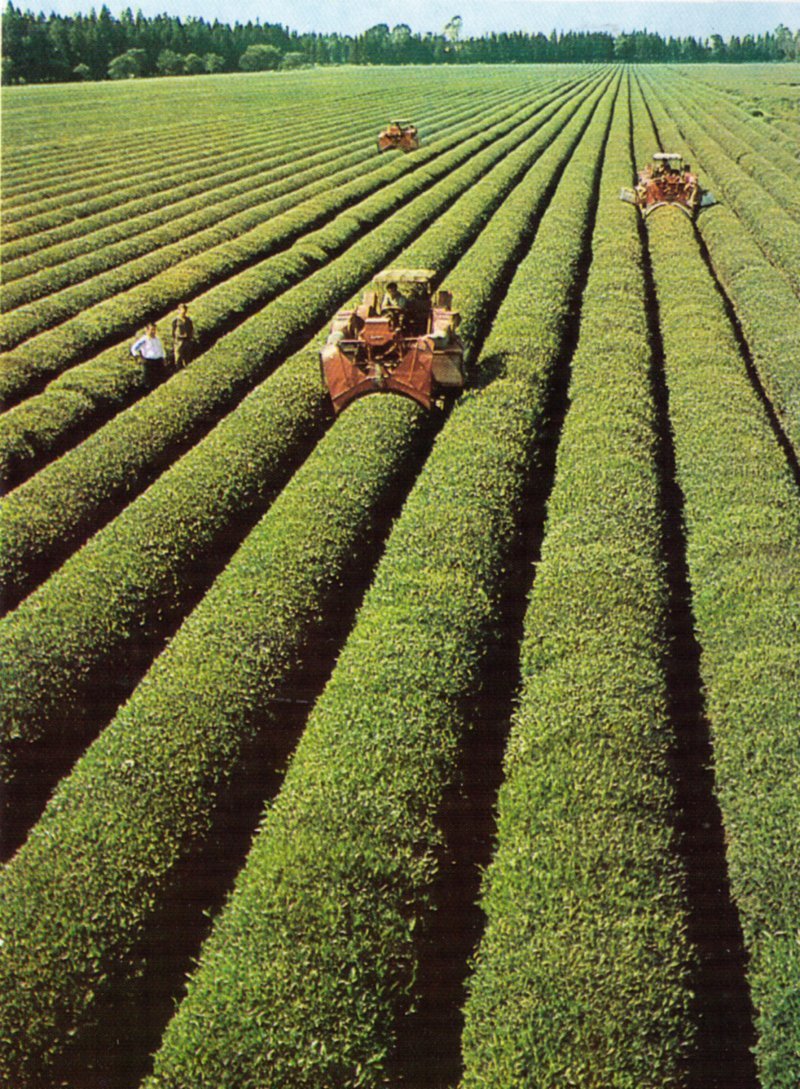

Tea comes from a small tree that has been cultivated and transformed into a bush for convenience. The black substance we drop into a teapot consists of specially-dried leaves. Anyone who has visited Georgia knows what a tea plantation looks like: it is a sea of firm green waves. Tea-pickers with baskets gather the leaves all through the summer. Tea-picking is as difficult a job in Georgia as it is in China, India, Sri Lanka and the Argentine, and there was no hope of making it any easier. Norbert Wiener, the father of cybernetics, who never placed any bounds on a designer's imagination, could only sigh when a tea-picking machine was mentioned. There were many other authorities who agreed that anything could be invented and designed, save a machine for picking tea leaves.

Yet, such a machine was constructed. The word "amazing" has become shoddy from use, but it is the only one that can describe a mechanism that possesses a picker's keen eyes and sensitive fingers. The machine was designed in Georgia and is shown here in action. One must bear in mind that the blades do not simply trim the bushes, they pick out the tender top leaves, which alone produce the inimitable fragrance and taste we know as tea.

However, picking the leaves is only the middle link in the chain that begins with planting a bush and ends with the teapot on your table. This seemingly modest bush calls for special care and attention and has long been accepted as the most difficult plant to cultivate. There is a saying in Georgia: "You must bow down to the bush fifty times to have real tea."

There is still much to be done after the leaves have been picked. A thousand secrets in the drying process produce each given shade and variety of tea. There is green tea, preferred by the Uzbeks, Tajiks and Turkmenians; brick tea for Kalmykia; and the black fragrant tea in tinfoil packets which can be found in most every home today.

Let us return to the story of tea, however. It was first introduced to Russia three hundred years ago, when the Tatar khan presented Tsar Mikhail Fyodorovich with 144 pounds of an unknown dried leaf "for brewing tea". The tsar and his boyars liked the new beverage. Thefollowingentry appears in the Chronicles of the time: "It is a good brew and fully satisfying when got accustomed to." The first tea merchants set out from Muscovy to Peking in 1696. Within a short time the new beverage became very popular. Russia did not skimp on paying gold for tea. Tea from China was brought to Europe by ship, by camel caravan, in sleighs and horse-drawn wagons. Perhaps it was the samovar that gave Russia the reputation of being a tea-drinking country. This still holds true today, for we consider ourselves to be among the greatest tea-drinkers in the world. As we sat around the table in Georgia, someone asked which country consumed the most tea per capita and the answer was: Great Britain, with Canada, the Netherlands, the Arab countries, Japan, the USA and the USSR following. Most surprising is the fact that the tea-producing countries of India, Pakistan and China are last on the list. If Georgia were to be included, it certainly would be last of all. One might wonder why this is so as concerns India and China, but there is no mystery about Georgia.

Georgians have been wine-drinkers for centuries. Today, as ever, wine is the preferred beverage. The first tea bushes were planted less than a hundred years ago. In 1899 there were only 56 hectares of land under tea. Today Georgia produces 96 per cent of the nation's tea and is one of the largest tea-producing areas on earth. Its tea plantations are like the wheat fields of the Ukraine. There are many regions in our country where one cannot imagine everyday life without its numerous cups of tea.

On the one hand, if you ask for tea in a cafe or restaurant in Georgia the waiter will raise his brows and say: "There's wine. Why order tea?" In a house standing next to a tea plantation your host will set a bottle of wine on the table, but never serve tea, for it is considered poor taste here to offer a guest tea. Such is tradition. However, there is a change in the air, and Georgians are finally beginning to appreciate the value of the crop they have been raising. A magnificent teahouse has been built in the center of Tbilisi. So far, it is the only one of its kind in our country. The tea here is always wonderful. This is where tea-raisers and selectionists meet, where tea-testers gather and where, on leaving Tbilisi, one can buy a gift-packaged box of superior Georgian tea as a souvenir.

Samovar, Stepan Nesterchuk

Tea needs no advertising in other parts of our country. However, one must admit that we do not often drink if as it was intended to be: fragrant and tasty. Brewing a cup of tea is not a difficult task, yet it takes skill. Does one always get a good glass of tea in the many eating places scattered all over the country? As often as not, one is served a reddish-brown liquid lacking in taste and aroma. This means an indifferent or untrained person has brought to naught all the painstaking work of the tea-raisers.

As for our own homes, the good old times of our grandfathers' samovars are somehow gone forever, though tea is still a wonderful way of bringing people together. Here are some lines from an ancient manuscript: "Tea provides vigor, softens the heart, banishes fatigue, awakens the mind and wards off sloth."

My grandfather was a semi-literate peasant, yet I heard him quote this saying at the tea table.