One February morning a young man in a sheepskin coat was stopped outside of Moscow for an obvious traffic violation. He was riding a motorcycle that had a crude metal ski instead of a front wheel.

The sergeant on duty had a look at his license. A moment later he was smiling broadly. "You mean you've come all the way from Magadan?"

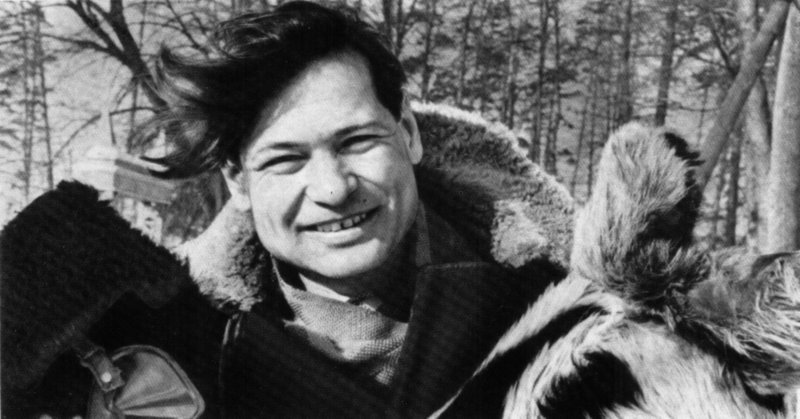

The next day we invited the young man over to our editorial offices and gathered round, staying on late into the night as Tikhon Khudoyarov told us about his unusual journey by motorcycle from Magadan in Siberia to Moscow.

This is his story.

Seimchan, a settlement of miners and geologists, is located far in the north, in the Kolyma. I'm a technician there.

Motorcycles are my passion. We have a sports club and began talking about a Magadan-Moscow trip a year and a half ago. I saved up my vacation for three years so I could take off five months, starting last summer. The first thing I did was go out and buy an IZH-56 motorcycle. Then I began preparing for the journey.

This was the best type of motorcycle for a cross-country trip. I didn't get bogged down with equipment, since I was only going to take along the bare necessities. I packed my tools, some spare parts, a cape-tent, a gasoline can, a couple of day's rations in a metal box and a suitcase with a coat and suit for Moscow, a pair of felt boots, some books to read on the way, my maps and a diary. By the way, I bought a copy of Traffic Rules and Regulations for travelling in big cities, but I never even opened it.

I boarded the llyich and arrived in Nakhodka from where I started out on my journey on October 5th. From there I rode through the splendid groves of the coast. The leaves on the trees were yellow. I had to cross Siberia and reach the Urals as fast as possible, before the first blizzards covered the roads.

I reached Khabarovsk three days later. This was the end of the first thousand kilometers. A hunter took me across the Amur in his boat. A day later I reached Birobidzhan.

Swamps and mountains lay ahead. For many hundreds of miles I had only footpaths and trails to guide me. Once I spent a whole day crossing a swamp. There were plank walks for people on foot. I wheeled the IZH along the planks, missing my step and plunging into the bog every few feet of the way.

There were many days on which I couldn't do more than ten kilometers. I learned how to weave mats of switches to put under the wheels in the worst spots. The motor never let me down, but the generator once did. Water got into it, and that squelched my plans for reaching a railroad junction before nightfall. I had to wheel my IZH in the dark the last two kilometers of the way. I fixed it so the next morning that even if I decided to ride across a river it wouldn't get wet.

I tried to keep to the railroad tracks. Engineers would stick their heads out of the cabs of passing freights and wave to me.

I finally reached Obluchye Station and went in search of a focal hunter who might show me the trail, for you can't manage without a guide in those parts. The guides passed me on from station to station, across swamps and over mountains all the way to Arkhara. The swamps there are really something. I kept wondering when they'd end, but they just kept getting bigger and bigger. Finally, in Arkhara, there was a paved road. It was smooth going from there on. When I got to Svobodny I set out to look for a schoolteacher named Alia Boboyedova so I could deliver a letter from her friend Lyudmila Lutova in Seimchan. Svobodny is a small town, but it has several schools. It took me half a day to find her.

Then I spent three hours trying to get the motor going. The temperature had dropped to below zero, and the lubricant was frozen. The frost was good news to me. It meant I could cross any swamp or river now, even travelling as the crow flies. Soon it started to snow. Since the wheels kept skidding, I didn't cover much ground. I reached a forest towards night.

Piles of dead trees and brush wood blocked the way. I rode over and around till the chain snapped. I tried dragging the IZH, but it was too hard. By then I was so thirsty I decided to drink the supply of distilled water I had for the battery. My clothes were drenched with sweat. Soon a film of ice began forming on them. I made a campfire, threw on my cape-tent and got down to repairing the chain. A few hours later I had the motor running again, so I tossed some more wood on the fire and went to sleep. When I woke up the sun was shining over the mountain. Everything looked bright and cheerful.

I slept in hostels at the different railroad stations or asked for lodgings at the last house of a village. People always took me in. I was given a letter in Skovorodino, to be delivered when I reached Sverdlovsk. Naturally, they could have mailed it, but I was glad they gave it to me. That meant they believed I'd reach Sverdlovsk.

I got into trouble twice in Chita Region. Just outside of Mogocha I lost my... motorcycle. I headed full speed right off a cliff, since I couldn't stop in time. I managed to jump off and hang on to some bushes, but the IZH roared right down the slope. I raced down after it to the river, but it was gone. Then I climbed back up the slope, thinking it might have got stuck someplace. It had vanished. I hated to think it was on the bottom of the river. After hunting around for about an hour I finally located it at the water's edge. There was hardly a scratch on it. Soon I was on my way again.

I hit a rock in the dark near the village of Ulei and was knocked out of the seat. As I lay on the rocky ground I could hear the IZH sputtering nearby.

"What are you lying around on the road for, scaring people?" It was a girl. She was leading a horse. She helped me to my feet and bandaged my bleeding elbow. Together we raised the motorcycle. The only damage was a loose exhaust pipe.

A highway lined with planted larches brought me straight to Chita. I had my first flat there, on a city street, of all places!

There were huge snowdrifts at the approaches to Tomsk. Trucks were buried under the snow. You could hardly see the telegraph poles. I had to stop every so often and tighten the handlebars and then push the IZH through the snow. I was "approaching" Tomsk all day and all night. Towards morning of the second day I was so exhausted I sank down on the snow and fell asleep. Nikolai Pugachov and Leonid Zheleiko, two tractor drivers, stumbled upon me and dug me out. I was darn lucky, because my warm clothes kept me from getting frostbitten.

I reached Novosibirsk in the middle of December. I used to live there before I moved to the far north. Still, I lost my way the moment I entered the city. It took me a good half-hour to reach a street I recognized. I rode past modern houses. There were trolley-buses on streets that had once been the outskirts of the city.

People in Irkutsk and Tomsk told me that the going would be easier after Novosibirsk. I had no idea then that the people in Sverdlovsk would say: "Things'll be easier as soon as you cross the Urals", or that in Kazan they would say: "Wait till you cross the Volga..."

The next four days were spent in cleaning and oiling the IZH. Then a blizzard blew up. It lasted a day, and another, and a third. I was getting restless and decided to start out anyway. When I reached Tolmachovo Station I found I was the last in a long line of trucks. There were huge snowdrifts ahead, and the temperature was down to 40 below zero (Centigrade), so I decided to sit out the cold in Novosibirsk.

It finally became warmer. The thermometer now stood at only thirty-five below. I started out immediately. I was anxious to see the obelisk marked "Europe-Asia", but missed it. I still regret it.

Just before reaching Malaya Purga ("Minor Blizzard") near Izhevsk I got caught in a blizzard. A day later it was raining when I rode into Yelabuga. My hosts tried to talk me into staying over, but I was impatient to be on my way. I asked for a map so that I wouldn't get lost at night. While going through a forest I took the wrong turn, reached the village of Verkhny Shurnyak at 2 a.m. and had to look for a place to spend the rest of the night.

I waded across the Volga, so to speak, since there was water on the ice that covered the river. The exhaust pipe bubbled and the wheels spun. I was soaked. When I finally reached the other side a man came running over. He had seen me crossing the ice and took me straight to his house to warm up and dry my clothes.

After I passed through the cities of Gorky and Vladimir there was not far to go to Moscow. When I was only seventy kilometers away I had another flat. I decided to take a chance and leave it alone, but I paid dearly for my foolishness. After about five more kilometers there was a loud crack. It felt as if the rear wheel had exploded. The IZH tilted and settled on the muffler. I had travelled across most of the country, through swamps and over snowdrifts to land in such a mess when Moscow was practically in sight!

I was smack in the middle of the highway, but I didn't care. I had no intention of moving. Some drivers detoured around me, staring at the wreck with interest. Others asked me what had happened and offered to tow me in. Not on your life! I am firmly convinced that there is always a way out of any situation. So I took off the front wheel, switched it to the rear and made a ski out of the remnants of the rear wheel, which had lost all its spokes and had a broken rim. Then I attached it in place of the front wheel. I was determined to reach Moscow under my own steam.

It was 9 p.m. and dark when I finally got through with the repairs. I'd be happy if I could do at least five kilometers an hour, I said to myself, but I didn't need a paved highway now. What I wanted was snow.

After a while I got used to the new arrangement and put the IZH into second and then third gear. The needle of the speedometer settled at 40. I forgot all about being tired. This was a new lease on life. I was on my way again!

Then the Moscow skyline came into view. It was 4 a.m. Trucks were clearing the snow off the streets. The ski screeched on the pavement. I could barely keep the motorcycle under control.