my regards to my house, the

orchard and my favorite

young oak. Give my regards to

my homeland...

Today's speeds make it possible to watch the countryside change in the course of a five- or six-hour trip. The forests of Russia thin out to the south, discarding their birch raiments along the way. The white flocks of trees that have lined the road all the way from Moscow to Serpukhov suddenly traipse off. Passing Serpukhov, the countryside seems evenly divided between field and copse. The terrain is hilly here, with ravines and dry valleys cutting through the green fields and forests.The horizon has moved off visibly, and there is more open space for the eye and the wind to roam.

Beyond Tula the distance becomes blue, with the intense green of oak groves replacing the sprightly white lattices of birch. There are not enough forests to preserve the small rivers and streams, so dams hold back the water in the ravines. The trees do not grow on the open plain but rather crowd along the dells and gullies. Single-standing wild pear trees, young oaks, or snowball trees adorn the hillsides. There is a festive feeling in the air. What could be better than to open the car door and race off across the powdery green of the young rye to the lone trees casting their long blue shadows? But the end of the road has been tightly wound on an invisible drum and so it moves on, dipping in the dells, fitting the slopes tightly. Cars look like colored bugs that have become stuck to this endless asphalt ribbon. A hand thrust out of the window will come up against a resilient wall. You feel that if you curl your fingers you can grasp a fistful of wind.

The log houses with carved platbands on the windows gradually give way to long, low brick or concrete homes with white window sashes and holyhocks in the front gardens and chain winches over the wells instead of long shadoofs. In time of yore this was a region of windmills, though we only caught a glimpse of one on a hill. The view became less encumbered and a rise in the road gave us a clear vista for many kilometers around. We could see the distant villages, islands of woods and groves. The line where the earth met the sky was a deep blue, becoming denser as twilight neared. Soon reddish lights began to flicker in the villages, making it seem as if the road lay across the sea.

"How far is it to Spasskoye?" we asked an old woman who was milking her cow by the road. A small flock of late-returning geese waddled in single file towards the barn. For a second the countryside was lit up by a reddish flash, as if someone had suddenly struck a match beyond the hill.

"Let it be so, Lord, let it be so." She was praying for rain.

"Can you tell us how far it is to Spasskoye?"

A landrail cried out from a dark, misty hollow. We could see the blue light of a TV screen through the cottage window. A ballerina was spinning in a blinding beam of light. The old woman was stone deaf. She went on milking her cow without as much as looking our way.

It was not far to Spasskoye. We continued on for another twenty minutes and finally reached the road post with "303" on it. This was where we turned off. After several rises and dips we reached the park. A house glimmered white in the dark. Peering more closely, we could make out the tree trunks and the paths. A cock crowed in the distance. Then, suddenly, right by the fence, an unexpectedly loud singing issued forth from a black bush. It seemed to make the leaves tremble.

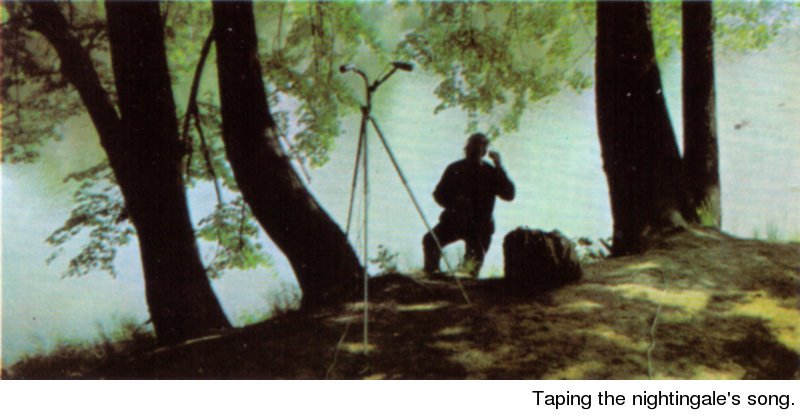

We unloaded our tape recorder, knapsacks and coils of wire, for we had come to Turgenev's park to tape the famous nightingales.

The early-morning singers were still holding forth. The local shepherd had just driven a herd down the road, and four excursion buses were already parked by the park railing. The passengers, students from Orel, were playing volleyball, waiting for the park to open.

We had set up our blind in the bushes, but now we were recording the slap of the ball in addition to the nightingales and a turtle-dove cooing. We had to put off our taping.

There have always been many visitors at Spasskoye-Lutovinovo. Lev Tolstoi came here. They say the two great Russian writers argued as to which park was better, this or the one at Yasnaya Polyana. The actress Maria Savina came here, as did the poets Fet and Nekrasov. Even in those far-off days of the 19th century, when there were many such estates of the landed gentry in Russia, Spasskoye-Lutovinovo was well-known. Turgenev did much to retain its glory, for he loved the gently sloping roads, the quiet ponds, the orchards and the islands of woods. From a distance the park resembles any other copse in the steppe, for all the best that grows in this part of the country has been gathered here in a living collection of lindens, mountain ashes, poplars, honeysuckle, birches, broom, oaks, maples, firs, ash trees and apple trees. The greenery, the water in the ponds, the birds, the folk songs sung in the village and hunting made up Turgenev's world. His ancestral home was here, at Spasskoye-Lutovinovo, and he cherished it, returning always after his wanderings to write and to hunt. "...My soul hungers for the nightingales, the scent of straw and birch buds, the sun and the puddles on the roads!" he wrote.

The only original buildings which remain are the stone mausoleum and the barns. The clapboard building with "Almshouse" lettered on it, the bathhouse and the white wing were all rebuilt either before or after the war. The large family manor which seemed like "a great city" to Turgenev in his childhood burned down in 1906. Nothing but the overgrown foundation stones remain. There has been talk of the house being rebuilt, but so far the park is the main attraction here.

Things have changed since Turgenev's time, for trees also die. The avenues of lindens certainly remember him, though, as do the shaggy firs whose tops can be seen from the Moscow Road. The meadows were surely as sunny and fragrant from sage and dandelions. The pond is the same, as is the field of rye and the village beyond, though the cottages have slate roofing now and are no longer thatched, and the name of the village has been changed for no good reason at all. It is difficult to understand why Petrovskoye was worse than the present name of Peredovik. Upon learning that Turgenev's mother was born in the village you feel sadder still. As I walked through the woods beyond Spasskoye Village I asked a local man where Kobylii Verkh is, having little hope of seeing it. His reply: "Over there, beyond the ravine," was like a gift. Some name places have a wondrous power of their own. Bezhin Meadow, which is about twenty miles away, would have lost all meaning and significance if it were ever renamed, no matter how attractive the new name might be. Fortunately, it is still Bezhin Meadow, as in Turgenev's famous story.

For some strange reason everything one sees here is later remembered as being different from the same things elsewhere. Although I knew that cornflowers growing in the rye, rooks cawing in the poplars and the little red crucians the village boys had caught and were carrying home in their caps could not have appeared otherwise, I still regarded the ordinary things I saw here as being different and unusual. I discovered once again that everything, even the most important things in life, are nurtured by ordinary, earthy springs.

Turgenev's home has come down to us as a great treasure. Thousands of people visit the estate each year, some arriving by bus, others hitchhiking, driving or hiking. Some want to have their pictures taken beside Turgenev's Oak and see for themselves that the tree-lined avenues do indeed form the Roman numeral XIX, which stands for the 19th century, as the guidebook says. Others want to commune with nature in the far reaches of the park where the air smells of dampness, where wild strawberries grow in the sunny patches, where you can discover a bird's nest and in the evening hear the song of the little warbler among the weeds. One hot noon I came upon a group of boys in one of the meadows. They had stopped for refreshments, which consisted of a loaf of bread and a large bottle of milk. Their knapsacks were set around them in the grass. A book lay beside them with a daisy for a bookmark.

"I see you're reading A Sportsman's Sketches."

They nodded and continued eating.

"Where are you from?"

They said they were from Mtsensk, which was twelve kilometers away. Their teacher had suggested they bicycle to all the places in the vicinity Turgenev had written about. I helped them find the shortest road on the map to Bezhin Meadow. Then we all fell silent as we listened to the birds. The boys chewed on sorrel stems, while I leafed through the book that has been a favorite with readers for several generations.

An inexperienced person will say that all nightingales sound alike. This is not so. Even nightingales in the same garden sing differently, and there are places in Russia where they sing especially well. There is good reason why we speak of the nightingales of Kursk. A brand of singers with unusually beautiful voices live in the gardens of Kursk, in the ravines and along streams whose banks are overgrown with wild cherry trees, nettles and blackberry thickets. This fact has been known for generations, and the opinion of the experts has not changed.

No one knows how the "Kursk school" of singing came into being, but it does exist. Even though a nightingale is a born singer, it will never become a virtuoso if the older nightingales do not tutor it. Obviously, a natural gift is of paramount importance here, as elsewhere. No matter that some birds have had every opportunity to learn, they will never achieve more than five different trills. There are many average singers, whose range is seven trills. A true artist, however, has a repertoire of from ten to fifteen trills, each one strong and clear and enough to bring tears of joy to the true connoisseur. One trill may imitate the cry of a black woodpecker, another is a shrill whistle, a third is the guttural cry of a kite. Some imitate the cuckoo's call when the birds are migrating. There is one trill that is known everywhere that nightingales sing in Russia. This warble is called the "wood goblin's pipes".

When you say the words aloud they reflect the awe of a person who has caught a sound familiar to anyone who has been in the woods at night. One can write a treatise on nightingales. It must by all means not only praise the singer's talent, but, so to speak, the ability of this fine species to compose. The bird chooses the most striking of the forest sounds for its song, and the nightingales of Kursk have mastered this best.

Those on the Turgenev estate should properly be called Orel nightingales. They are closely related to the ones of Kursk. Boris Veprintsev decided to tape the Spasskoye-Lutovinovo nightingales for his new stereo record of forest birds. We chose what we felt would be a most convenient time. The night air held promise of a summer storm. Thunder rumbled not very far away. A black stillness enveloped the dark, hushed park. All of its creatures lay still, save the nightingales. There it was: the wood goblin's pipes, so very close at hand.

It seemed that if we as much as moved a finger we would scare off the singers. Boris was in no hurry to untie the pouches that held the two microphones. Nightingales were singing throughout the park. We could have our pick and need not proceed in haste. There was a better singer in the distance. Soft warm clouds seemed to be grazing the tree-tops. We used a flashlight to find the path. The trunks of the lindens appeared white. Although nightingales are not afraid of light, we did not want to alarm them and so continued on in the dark, holding our hands out before us until we finally reached the pond. We felt around for a place to set up the mikes. There was a soft click. I could hear the reels turning in Boris' knapsack. Perhaps Turgenev had once come to this pond at night, too, to listen to the nightingales and this singer was a descendant of that other bird ... Boris handed me the earphones. I could hear a medley of sounds: the thunder, the clear song, the muffled sound of a train and a strange rustling. It had started to rain. We quickly gathered up our equipment and dashed across the park. The tops of the lindens were now swaying in the wind. There was a flash of lightning. A clap of thunder. Another flash. The building appeared momentarily, a blindingly-white square against the utter blackness. The wind lashed at the heavy branches.

We brushed the rain off our clothes as soon as we got in. The storm had died down. A soft rain was falling and it, too, was subsiding.

"They're singing again."

We turned out the light, but could not fall asleep for a long time. A warbler was chirping monotonously in the damp darkness outside, while the nightingales sang on like creatures possessed.

The furnishings of the old Turgenev house have been moved to a museum in Orel. There is a notable library, consisting of five thousand old volumes, the desk at which Turgenev did his homework as a child and later wrote many of his books, a billiard table, his bed, a large time-blackened icon in a silver setting, which, legend has it, was given to the Turgenev family by Ivan the Terrible. There is Turgenev's red Oxford gown and a photograph of him wearing it.

The curator, a pleasant man who knows his native city of Orel well and obviously loves it, raised the piano lid and touched one of the yellowed keys. The note he struck lingered in the air.

I do not know a town or city that cannot point with pride to a native son. This thought came to mind time and again during my travels. Take the tiny town of Rylsk. You suddenly discover that the famous explorer Shelikhov came from here. Kramskoi, Ryleyev and Marshak were born in Ostrogozhsk, while Mendeleyev and Yershov came from Tobolsk. In a word, there is no special "hothouse" where talents are sown and raised. Any spot on earth can produce outstanding individuals. Still, there are places that are mysteriously rich in famous sons. Perhaps Orel Region is first among these in Russia. The quote under the portrait of the writer Bunin in the local museum reads "I grew up... in that fertile semi-steppe region... where the fabulously rich Russian language evolved and from whence came most of the great Russian writers, with Turgenev heading the list."

Who were they? They were Bunin, Turgenev, Fet, Tyutchev, Leskov, Pisarev, Leonid Andreyev and Prishvin. If we go a bit beyond the bounds of Orel Region, names such as Lev Tolstoi, Koltsov, Andrei Platonov and Yesenin can be included. What produced this veritable galaxy? Bunin spoke of the Russian language evolving in these regions. One can add that the countryside in this part of Russia was most conducive to nurturing an awakening talent for writing. All of the above writers had a special affinity for describing nature. And then there are the nightingales, which sing most sweetly in these parts. .. Indeed, the very soil here contains a secret all its own.