I'm on the side of a 13,000 foot volcano in a windstorm.

“You need to run for this next part,” one of our guides instructs in Spanish. “The trees are dead so the wind might knock them over and crush you.”

Um… ok. I turn to relay the happy news to the rest of our hiking group. We pass a skeptical eye over the bare tree trunks that sway next to the trail.

"You're kidding, right?" the Dutch boy in our group says.

I shrug. “Maybe he’s just trying to scare us, or maybe I just misunderstood.”

We decide not to take any chances and rush past. It’s just one more trial on the journey up Acatenango Volcano in Guatemala.

Our hike began on a steep, dry, dusty trail through corn fields, wound up through a muddy fern-filled jungle, and now passes through this semi-desolate landscape in the clouds.

I had a hard time of the climb at first, barely keeping up with the head of the pack even though Nash carries our tent. A puff on my inhaler cleared the phlegm from my lungs, but the biggest help has been the distraction of conversation with our three guides.

As the best of the English-Spanish speakers in the group, I act as translator. It’s I role I don’t take to naturally, since it involves always being in the center of attention. Even after three weeks of Spanish lessons, I still make constant blunders (so take all information here with a grain of salt). At the same time, it's amazing how much you can learn with even a basic grasp of the language.

Our guides tell me how some enterprising individuals come to the mountain to collect moss off the trees and sell it in the market as Christmas decorations. They point out the clothes and debris left behind from an old plane wreck and inform me that, just a month previous, the leader of their organization rescued passengers from another plane crash on the volcano next door.

A Guide's Tale

But the most riveting story is how our group of guides came to be.

Jaime, the lead guide of our trip, lived for several years as an illegal immigrant in the United States, first in Texas then in Iowa. He was caught in part of the infamous Postville raid in 2008, when Homeland Security agents stormed a kosher meat-packing plant and deported 389 undocumented workers, almost all indigenous Guatemalans. His ex-wife and children stayed in the United States, and he hasn’t spoken to them since.

Back in Guatemala, the group of deportees returned to their same old village with the same old lack of economic opportunity. They started planning to sneak back into the United States, but the the Guatemalan National Council for Attention to Migrants, or Conamigua, stepped in and teamed up with Guatemala's tourism agency to train them to be guides.

Jaime's brother, Gilmer Soy, leads the group - he speaks fluent English and handles the administrative side of the business. Jaime and the other guides lead two or three tours up the volcano every week, while the women prepare all our meals. Even the kids chip in by renting out walking sticks and warm hats for 5Q.

A portion of the price of each tour goes toward community projects, and the guides work part of the year without pay to funnel more money into better infrastructure and new schools for their village, San Jose Calderas. We get to see the progress for ourselves with stops at Gilmer’s house before and after the hike.

In addition to guiding tourists up the volcano, the group also serves as park rangers for the area. They lead conservation efforts and perform search-and-rescue operations. When we come across a group of yellow-vested people picking up trash off the mountain, Jaime’s chest swells with pride as he points out uncles and cousins among them. They’re also planning on constructing their own private route up the other side of the volcano. It's clear that the Conamigua measures have given them a part of their homeland to care about.

Meet the Neighbor, Fuego

All the conversation has made me forget about the burning in my lungs and thighs. However, the other girls in our group aren’t so lucky, and the guides step in to help carry their packs.

Finally, we get the first glimpse of the payoff for all our effort. The clouds part, revealing a dark cone of earth bubbling out plumes of smoke and red-orange globules. This is our closest neighbor, Volcan Fuego.

We shout with excitement and Jaime reflects our enthusiasm with open grins. “You don’t normally see the lava during the day!” he says. This sounds like one of those lines that guides use to make your trip feel special, but I’m still impressed.

But by the time we reach camp, set up our tents, and settle around the fire, I start to think something is up with the volcano. I heard that it typically only “goes off” once an hour, but since we came within range of its rumble it hasn’t stopped spouting lava.

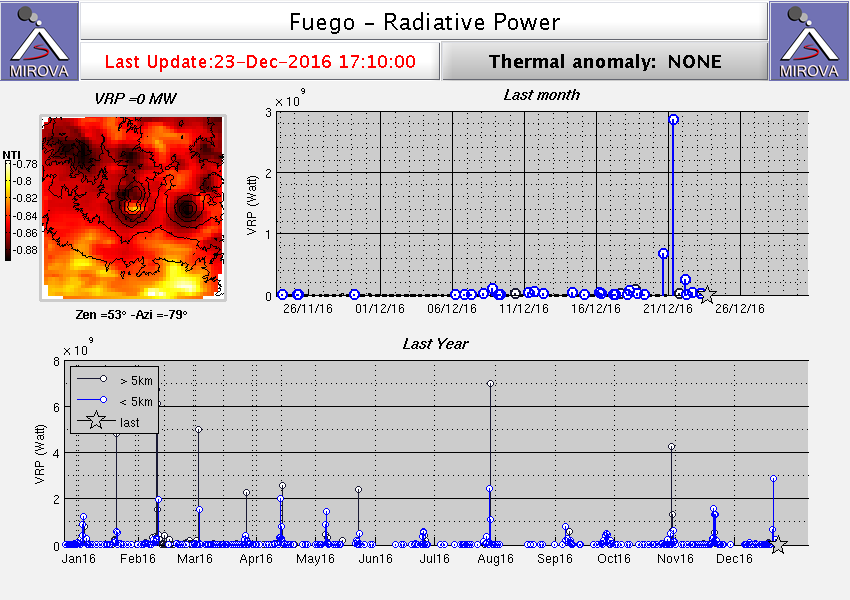

It turns out that Volcan Fuego has a violent “paroxysm” every 22 days or so. Wednesday December 21 just happened to coincide with one of these. I couldn't believe our luck!

And so begins one of the most intense nights in my life...

The group huddles in a little sphere of warmth around the fire. Our gazes drift between our little fuego and the big Fuego while the guides cook up hot pasta and roasted veggies.

“It would be nice to have some marshmallows, huh?” Jaime asks as we’re wrapping up our meal.

“I know!” I say. “It feels like I forget marshmallows every time I go camping.”

With a mischevious grin, he pulls out a bag of marshmallows. When he distributes Nash's share, he repeats his joke of the night before bursting into laughter: "50 quetzales, por favor." We drop the marshmallows into our hot cocoa and toast them over the fire.

In our private tent, the erupting volcano is out of sight but not out of mind. Its rumble is deep and continuous, like a jumbo jet taking off the in the middle of an earthquake. Occasionally, it emits a particularly violent hiccough that booms and lights the tent's wall with a warm glow.

Meanwhile, the wind still howls. During gusts, the tent bends in half and brushes our faces before snapping back into place. The tarp overhead crackles like a machine gun.

The combined din makes it impossible to sleep, and the cold is even worse. Nash and I climb into the same sleeping bag and pull the second one up around us. There, we cling to each other and shiver until 4:30am, when the time comes to decide whether to continue our hike up the mountain. I crawl out into the cold dark, and Jaime approaches.

“In my professional opinion, it’s not worth it to go this morning,” he explains. "It will be even colder and windier at the top, probably icy, and the view isn’t much better. But I’ll take you if you want."

It’s a difficult decision. Of course I want to conquer to peak - what better place to watch the sunrise? But even with four layers of clothing on, the cold has seeped into my core. No one else is even stirring. I decide to put my own and others’ comfort above the call for adventure.

“Let’s stay,” I say, and Jaime does a masterful job at not appearing relieved.

I crouch outside the tent a little longer, holding onto a root so the wind doesn’t knock me off our terrace. The sky is clear and stars twinkle in the backdrop, outlining the silhouette of another active volcano, Pacaya, to the left. But I can’t keep my eyes off the main show.

Two of Fuego's three vents send sparks of molten rock high into the sky. I'm mesmerized by their slow rise and fall and the way they skitter down the volcano's flanks.

It’s not long before the cold forces me back into the tent, where my hands come back to life with a long scream. We wait out the remaining early morning hours back in our sleeping bags until the sun comes up and warms the air.

Even though we didn’t make it to the top, the experience still felt like the definition of epic. After all, it was the first time I've spent the night perched in a tent on the side of a volcano while watching another volcano shoot the earth’s innards into the air. Pure awe.

Resources

- Acatenango Volcano Tours

There are many organizations and guides that will take you up the volcano. Overnight tours range in price from $20 to $120 a person. At 300Q ($40) a person, our trip included transportation to and from our lodging in Antigua, entrance fee, three meals, three guides, backpack, tent, sleeping bag, sleeping mat, and jacket. Hiking sticks, hats, and gloves were available for rent for 5-10Q. Make sure to pack extra snacks, warm clothes, plenty of water, and altitude sickness medication if you're susceptible. To make a reservation with the Conamigua group, contact Gilmer Soy through email at sologui5630@gmail.com or on WhatsApp at +502 4169 2292. - Fuego Volcano News & Eruption Update

Keep track of the volcano's status before your own trip.

Original post is on my blog and all content is mine unless otherwise stated. (See my introduction for evidence of identity.)