These two photographs were taken from an airplane many years apart. The first was taken in 1929 and shows the valley of the Ural River. It was chosen as a site for a new construction project to be known as Magnitogorsk. The second photograph shows the same area today.

The site and everything that was built on it were named after Mt. Magnitnaya. Naturally, everyone who comes here wants to see the famous mountain for which, they say, Japan once offered the Russian tsar 25 million rubles. But where is the mountain? It is nowhere to be seen. Far below the plane we sighted a toy excavator and a freight train snaking along. "The mountain used to be right here, where the excavation is," I was told.

White, reddish and grey clouds stretch off into the distance as far as the eye can see. On a clear day, when the smoke and steam rise straight up into the sky, one can try to count the stacks. I counted two hundred and seventeen and then lost count. It was a veritable city of strange, dark structures: bridges, pipes, cranes and a row of black furnaces. All were enveloped in white smoke. I later learned that tens of thousands of people come to this iron city each day. But where were they? The city seemed deserted, for so great was the area and the size of the structures.

In the course of a day I barely completed the journey the ore takes from the pit to the foundry shop, where a red slab of steel runs out between the iron rollers, showering sparks in all directions. This red dough begins moving faster and faster as it is transformed into steel sheets that whiz through the mill like fiery birds, giving the uninitiated a weird feeling. Nearby is another shop that is just as long. Here the steel is rolled until it is practically as thin as paper. In other shops it is formed into rails, wire, steel ribbon and strips, girders and various shaped forms. During the war plate armour for tanks was rolled here. I understand the largest of the shops will be making sheet iron for the automobile plant in the city of Togliatti on the Volga. This is the latest order the country has placed with Magnitogorsk, although this is no news in itself. Magnitogorsk has been swamped with orders from its very inception. If not for Magnitogorsk we would not have had tractors in time. Nor would Stalingrad have been able to hold out, for every other shell and every other tank was made from steel smelted in these blast furnaces. Today as always machines, ships, combine-harvesters, pen-points and needles are all made of steel. A great mountain has been turned into steel!

My first day at Magnitogorsk I interviewed the plant's director and the director of the municipal theatre. In replying to my question as to what was now of paramount importance, Feodosy Voronov, director of the plant, replied: "Ore! Ore and more ore."

Anatoly Rezinin, director of the theatre, has other cares. He simply had to find fifty pairs of bast shoes. "We spent the past two months in futile searching. Finally, we came upon an old man in Chuvashia who remembers how to make them. We've written to him and are waiting for a reply." The local theatre is rehearsing Construction Front It is about the very first year at Magnitogorsk, and that means bast shoes are a prerequisite.

While in town, I saw an old newsreel. We may speak fervently of Magnitogorsk, the Dnieper Power Station and the city of Komsomolsk-on-Amur, but no words are more stirring than these patched old reels. I saw men digging the foundation pit for a blast furnace. They were tossing the earth up from terrace to terrace by the shovelful. This was the very first foundation pit. There was so much else that still had to be built all around it, for the plant had not merely been designed as a modern plant, but as the largest existing plant in the world. The construction site had been located in the midst of a great wilderness. Few people abroad had faith in this venture, including our well-wishers. But these people with shovels did. Some shots in the newsreel were taken during a January blizzard. One has the impression that milk has been splashed over the screen. Men and horses were caught up in the cold, whirling mass of snow. A shiver ran down my spine. Yet, work never stopped for a moment, not even on these winter days. In the evening the workers gathered in their tents and crowded barracks, around a sooty boiling kettle. There were shots of bast shoes drying near a stove. This was the kind of footwear that was common in those days. The cameraman who filmed all this for future generations also believed that the people of Russia would someday wear real shoes and that they would look back in amazement and wonder whether all this had really happened.

Magnitogorsk at the time was a test of the Komsomol's strength. Komsomol members volunteered for the hardest and most responsible jobs. The entire country stood by the cradle of Magnitogorsk, as it were. One hundred and sixty factories were putting out equipment for the future plant. One hundred and eight schools and colleges were training workers and engineers. One hundred thousand peasants from the villages of Russia came to the Urals, bringing their home-made wooden suitcases, their spades, axes and saws.

Washed clean by the rains and dried

And golden-red fires burned bright

On the russet rough rocks of

I read these words in concrete on a monument in the shape of a tent recently erected by the people of Magnitogorsk in memory of those very first years.

Thirty-four months elapsed between the day the first tent was pitched and the day the first steel was smelted. Those in the know then could not but be surprised by this tempo. Today our country is building on a tremendous scale and at great speed. However, I will still say Magnitogorsk was our greatest victory. It is not only the pride of the Soviet Union, for of all the major construction projects undertaken in this century it is among the most outstanding.

The people who built Magnitogorsk are still among us. There are thousands of them. In deciding which of them I should write about I realized that there were probably people from my native region among the builders, since all of Russia had sent volunteers to the site. I would try to find them. Surprisingly, I had no difficulty in doing so.

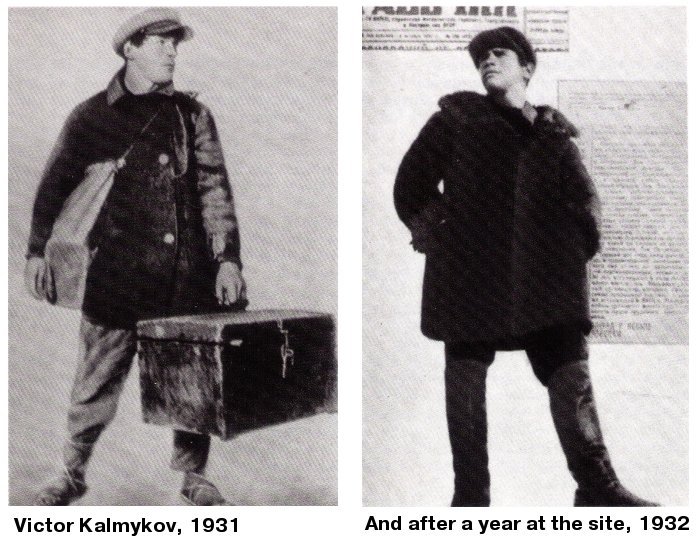

The first of these men was Victor Kalmykov. These two photographs, taken a year apart, show how he changed. The young fellow from Kalmykovka Village who came to the site in 1931 carried a wooden suitcase, had on bast shoes and a tattered jacket and his expression of wariness was typical of the peasants then. In 1932 one of the magazines put out a special issue devoted to Kalmykov. There is no sense repeating all that was said about the difficulties the builders encountered. Victor Kalmykov experienced them in full. What I would like to say, though, is that these difficulties and privations did not break a man, they elevated him. See the sense of dignity and workingman's confidence on the second photo! See how firmly this very same fellow, Victor Kalmykov, now stood upon the earth. He was a plain laborer, then became a concreter and, when it was time to assemble the first furnace, a fitter. Victor was illiterate when he arrived, but when he joined the Communist Party a year later he wrote his application himself. One can only wonder when this young man was able to study, since he was busy working from morning till night. Yet, at the time, the entire population was working and finding time to study all the same.

Victor Kalmykov died in an accident shortly before the war. He is still remembered here. He was a fine person, one of the hundreds of thousands who created Magnitogorsk.

Alexei Shatilin is another man from my region. He is now as old as Kalmykov would have been. He came to the site from a village near Kursk and took part in firing the first furnace. Shatilin went on pension seven years ago but then decided to return to the plant. He was standing by the furnace when I first saw him, squinting through a blue glass as he watched the smelting ore. It seemed to be a difficult moment, for dozens of experienced men stood waiting to see what Shatilin would say.

That evening I sat at the table in his house, drinking tea. He told me of the firing of the first furnace, and of the second, which was named the Komsomol Furnace. He spoke of accompanying the first trainload of cast iron to the Hammer and Sickle Plant in Moscow. While there, he met with various government officials. Sergo Orjonikidze stopped to speak to him by the blast furnace and, recently, so did Premier Kosygin.

All ten of the blast furnaces were built in his time. Shatilin took part in the first smelting of each, getting to know each of the huge furnaces which are as tall as a many-storied building.

"So you want to know about the temperament of the furnaces?" he said. "Well, no two are alike. They can be as finicky as people, and as generous."

"You probably have your favorite one, don't you?"

He thought this over for a moment and then smiled. "Yes, I guess I do. It's Number Six. We fired it during the war, with boys from the trade school as my helpers. That's where I got burned. What do I mean? Well, the metal splashed and they had to pack me off to the hospital. I got my first Order of Lenin working at Number Six. That's when we found a way of improving the smelting and got a bonus. Bring me my jacket, Mother!"

His wife hung his jacket on the back of the chair. Affixed to it were the emblem of a Lenin Prize winner, three Orders of Lenin, two Orders of the Red Banner of Labor and the Badge of Merit.

I took out a pencil and paper to figure out how much cast iron the old master had smelted in his thirty years at Magnitogorsk. The total was twelve and a half million tons.

Konstantin Khabarov lives a floor above Shatilin. He is also a First Class Master. These are the only two men at Magnitogorsk who hold the title.

Khabarov began working under Shatilin at the famed Number Six in 1943. At the age of fifteen he was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor. For many years he observed Shatilin's virtuosity, since a steelmaker's skill is truly an art. Although modern furnaces are equipped with dozens of complex instruments, the master's practised eye peering through a blue glass will still determine exactly what is going on inside the blazing inferno.

Konstantin Khabarov was sent to India to build and fire the blast furnaces at Bhilai. Some time after they had been handed over he was urgently summoned to Moscow and told he would be flying to India immediately. The steelmakers at Bhilai had done something wrong and a column of cast iron over eight meters across had hardened inside one of the furnaces. This meant the furnace had to be dismantled and rebuilt. The Indian press splashed the news across the front pages: the giant metallurgical plant had come to a standstill. The matter was to be discussed in parliament the following day.

Then four Soviet steelmakers arrived at the scene. The factory yard was full of hardened cast iron. All was confusion. At first, they had difficulty in finding out what was wrong. Within the next twenty-four hours the case was diagnosed. The Soviet steelmakers told the director of the plant that this was February 12th and that by the 20th the furnace could again be fired. The bearded director shrugged and said : "You've even named the day. This is no laughing matter."

For two hundred hours without a stop they worked inside the cold furnace, doing a job that only steelmakers can appreciate. Bit by bit, and then one cubic meter at a time, the hardened cast iron was scraped away with the aid of oxygen. Khabarov did not sleep for ninety-six hours. On February 20th the furnace produced its first iron.

"They offered us a staggering sum, but we refused, we said we never take money for helping. So we were invited to tour India. For a whole month we travelled all over the country, visiting factories built by the Germans and the British. It was good to know that our furnaces at Bhilai were better. The Germans and the British welcomed us as top-rate steelmakers and were always impressed when they found out we were from Magnitogorsk."

I have only named three men from Magnitogorsk, three men who originally came from my native region. Yet, most of us have fellow-townsmen or fellow-villagers working at Magnitogorsk, a great project built by people from all over the Soviet Union. That is why the word "Magnitogorsk" means so much more to every one of us than simply iron and steel.