The VIVA economic system, a grand vision pioneered by @williambanks , is fast becoming a reality. As one of the earliest crownholders, I've had the enormous privilege of watching its scaffolding go up bit by bit over the past several months.

I like the transparency that William and his team bring to the whole creative process; as a case in point they've made the writing of their whitepaper an unusually public endeavor, open to critique and discussion first on the VIVA Slack and now on https://chat.vivaco.in

This post is my entry in the whitepaper design contest detailed here: @vivacoin/viva-contest-so-you-think-you-can-graphic-artz

I now humbly submit my work (which consists of several diagrams and accompanying explanatory text) to the judgement of the VIVA team and my fellow crownholders. Even if you guys don't decide to use any of these, maybe it will at least serve as a stepping stone in the right direction. I'll upload the PowerPoint file to https://chat.vivaco.in so it's easy for you to make any necessary tweaks / adjustments.

Keep in mind this is directly based off my interpretation of the whitepaper draft & chat discussions, and my understanding may be incomplete or flat out wrong. @williambanks if I'm way off the mark on any of the concepts, please let me know and I'll be happy to make revisions.

Note: I am not attempting to re-write the whole whitepaper so some terminology is not fully explained. I focus mainly on the liquidity pool as this is one area of the whitepaper not yet fully fleshed out.

How VIVA gets minted

Besides setting basic economic parameters such as the target price of VIVA coins and how many coins can be minted in a given time period, crownholders also directly grant mints the authority to carry out their function. The "proof of authority" method replaces the PoW / PoS mining used by more traditional cryptocurrencies to generate new coins.

This authority is represented by the concept of a Treasury Right (TR), which is literally a digital license for a mint to print money. TRs themselves can be bought & sold on the open market provided by the TradeQwik exchange.

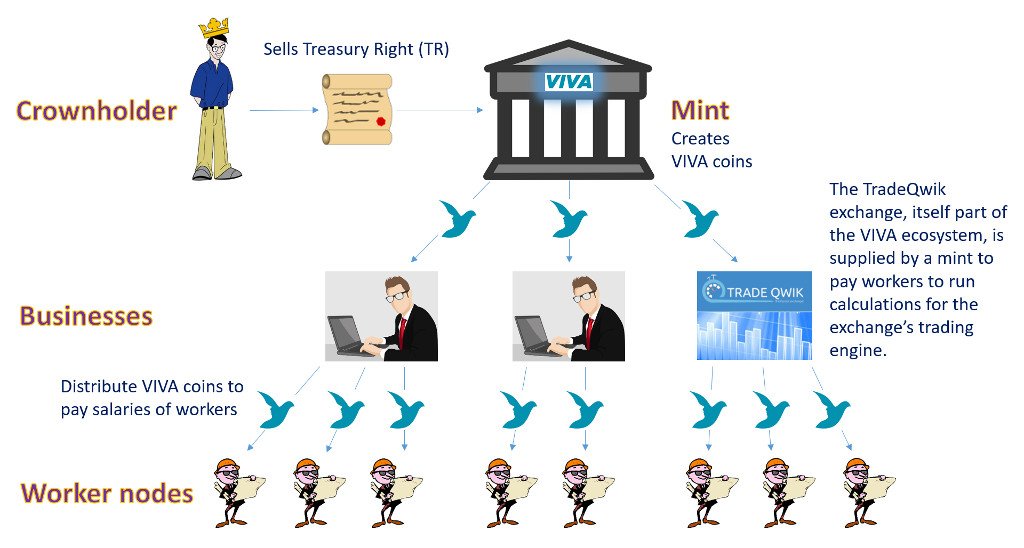

Crownholders are able to grant 1 TR for every VIVA Crown that they own. The process of using TRs is shown in the below diagram:

Figure 1: the VIVA distribution process

- A crownholder sells a TR to a mint.

- The mint uses the authority provided by the TR to create new VIVA coins.

- The minted coins are given to whatever businesses are attached to the mint.

- Businesses distribute the coins to pay the "salaries" of worker nodes that are performing some task for the business.

Note that it is perhaps more accurate to say the TRs are rented rather than sold; they expire after 90 days, at which time the crownholder can turn around and sell (rent it out) again.

Taking a dip in the liquidity pool

Another major component of the VIVA economic system is the liquidity pool, which represents the ultimate coin sink to control the amount of coins in circulation. Anyone who owns VIVA coins can send them to the liquidity pool (or sink them in the pool, as we say).

Think of throwing a handful of physical coins into the ocean. The coins sink down into the deep depths, treasure unrecoverable and lost to you forever. So it is with sinking coins in the liquidity pool. The act of doing so actually destroys them. In return for performing this important service, which keeps inflation under control and limits the amount of coins in circulation, you are given a stake in the ownership of the pool. This stake is proportional to the amount of coins you have tossed in vs. the total amount of coins that everyone has tossed in over the lifetime of the pool. You can increase your stake at any time by sinking in more VIVA coins.

By now you may be asking, what are the benefits to owning a stake in the liquidity pool? Why willingly destroy your coins like this? The simple answer is: your stake entitles you to receive lifetime dividends from mints. And the bigger your stake, the bigger your dividends, which can be deposited directly into your VIVA account or re-invested to buy more stake in the liquidity pool.

One more important thing to note: crownholders can choose to sink their TRs into the liquidity pool instead of renting them to mints. This is essentially equivalent to buying a stake in the pool equal to what you would get by sinking in all the coins that the TR would entitle a mint to produce over its 90 day lifetime. You can think of the pool as a kind of master mint that exercises the TR and immediately destroys the minted coins instead of handing them out.

That all sounds fascinating, but can you give me a concrete example?

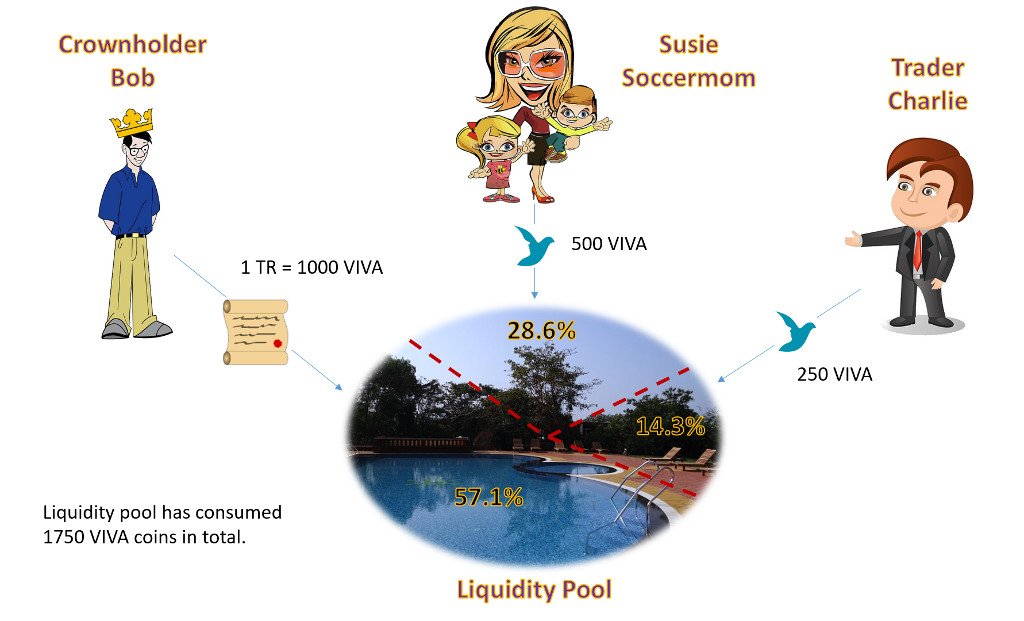

Certainly. Imagine we have 3 individuals, who together make up the total ownership of the liquidity pool, as follows:

Crownholder Bob - holds 1 crown, entitling him to control 1 TR. He chooses to sink that TR into the liquidity pool instead of renting it to a mint. The TR would have allowed a mint to produce 1000 VIVA.

Susie Soccermom - she runs a worker node for a business participating in the VIVA ecosystem, and has saved up a lot of VIVA coins over time from her salary. She decides to invest 500 of her VIVA in the liquidity pool.

Trader Charlie - he makes money trading VIVA price swings on the TradeQwik exchange. But he knows trading is risky business, so he decides to sink 250 coins into the liquidity pool each month as a retirement investment.

Figure 2: initial allocation of liquidity pool ownership:

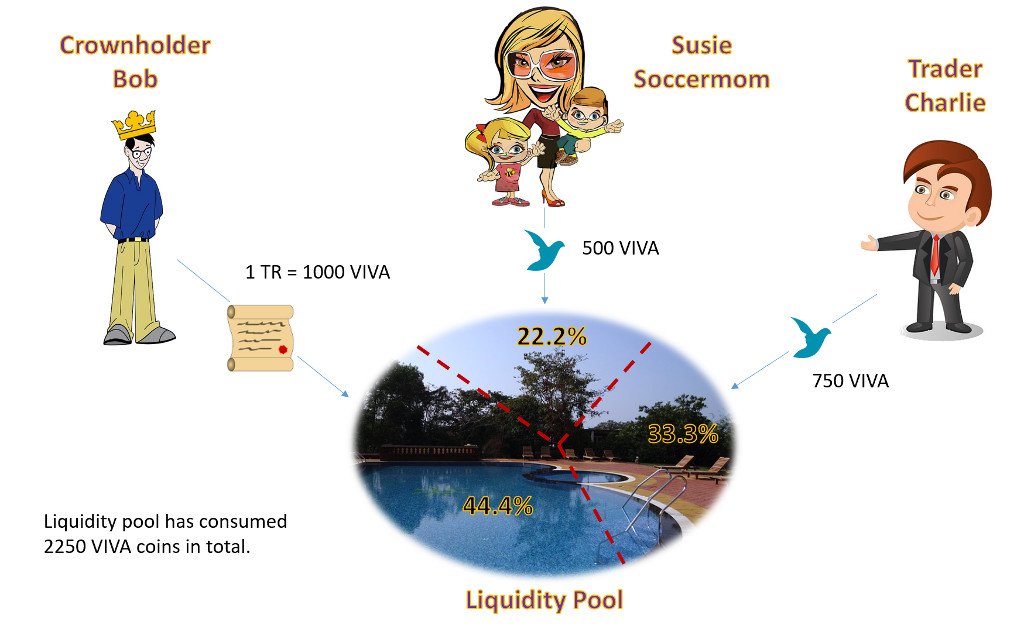

Figure 3: how the allocation has changed 3 months later

Charlie's ownership percentage has gone up because he has now contributed 750 VIVA coins to the pool (250 x 3 months). But Susie's percentage has gone down to accommodate Charlie, and so has Bob's (after 90 days he can renew his TR, but this time he decides to rent it to a mint instead of sinking it in the liquidity pool).

Mint interest rates

Let's dive a little deeper into exactly how mints create coins. As mentioned earlier, a mint needs to possess a Treasury Right (TR), obtained from a crownholder, in order to have the authority to mint coins. The TR is really a contract between a mint and the liquidity pool, which can be thought of as a master mint that all mints draw upon.

But mints don't get to produce coins for free. The TR contract basically states:

The liquidity pool agrees to allow you (the mint) to create X amount of VIVA coins over a 90 day period, but in return you have to pay the liquidity pool Y amount as a fee for doing so.

This fee is determined by an interest rate set by the crownholders. 50% of the interest collected in such a way provides the dividends that get distributed to pool stakeholders. The rest is used for a variety of other purposes that we won't detail here.

By setting the interest rate in different ways, crownholders alter the economic characteristics of VIVA which has a profound impact on the whole system. There are 3 basic scenarios to consider. Let's look at each, and for the sake of example assume that TRs grant the authority to mint 1000 VIVA over a 90 day timeframe:

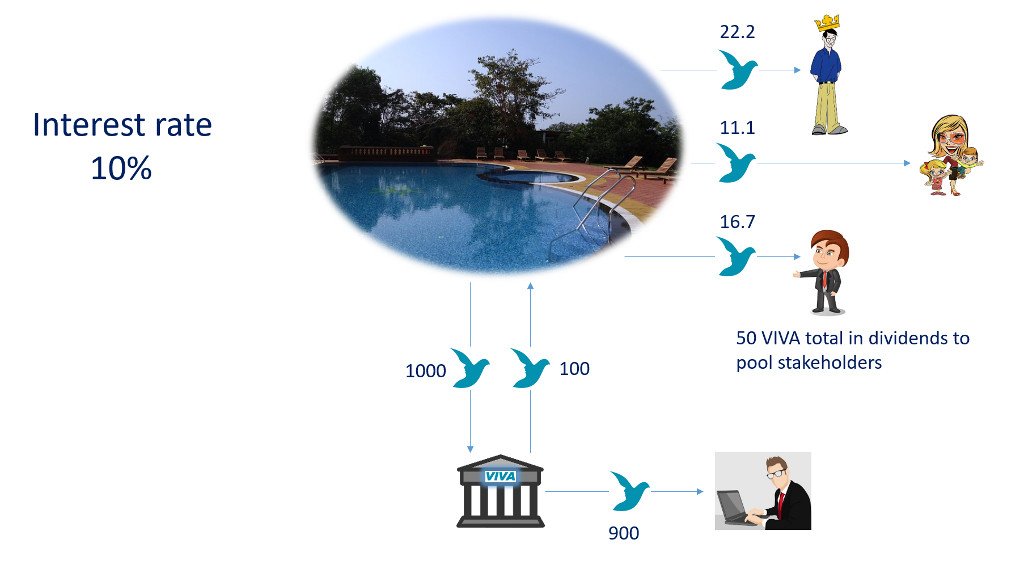

Scenario 1 - positive interest rate less than 100%

Let's say crownholders set the interest rate to 10%. A business asks its mint for some VIVA coins. The mint exercises its TR to create 1000 coins, but has to pay 100 to the liquidity pool. The remaining 900 go to the associated business.

Of the 100 coin fee, 50 go to the pool owners as dividends and the ownership percentages adjust accordingly if some people choose to re-invest their dividends.

Figure 4: businesses and pool stakeholders are happy; life is good

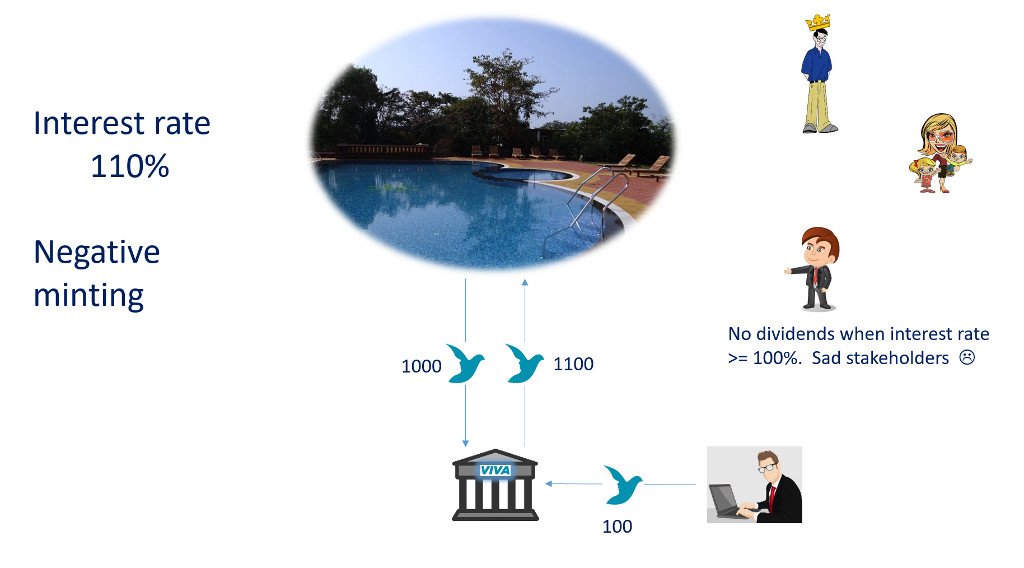

Scenario 2 - positive interest rate greater than 100%

We call this scenario negative minting because it reverses the flow of coins back through the mint.

This time, imagine the interest rate is set to 110%. As before, a business asks its mint for some VIVA coins to pay all those worker salaries. The mint creates 1000 coins, but has to pay the liquidity pool 1100. The 100 coin difference has to be paid directly from whatever reserves the business has on hand.

But the business still has to pay its workers, who are expecting their salary. So if the business has sufficient reserves, it makes more sense not to mint anything at all. And if the business hasn't set aside any coins for emergencies, it will be forced to buy VIVA on the open market, leading to increased demand driving up prices.

Also, with negative minting there are no dividends. The VIVA coins paid back to the liquidity pool are simply destroyed in the pool, vanishing from circulation.

Thus we see that if the VIVA coin price drops too low, negative minting is one tool available to the crownholders to push the price back up into more favorable territory.

Figure 5: businesses and pool stakeholders are sad; nobody is happy

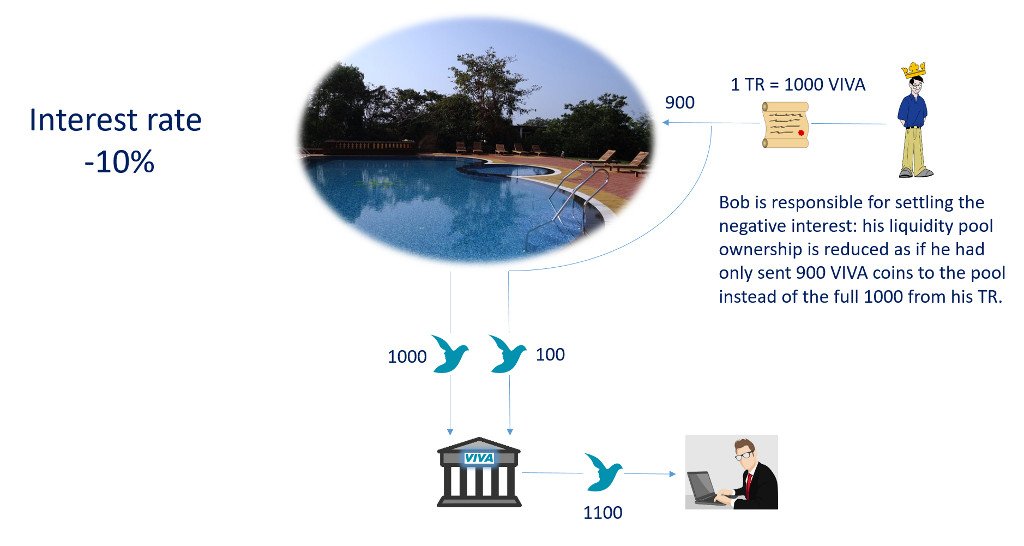

Scenario 3 - negative interest rate less than 0%

Now let's imagine the interest rate is set to -10%. When the business asks for money, its mint creates 1000 VIVA coins. But this time, because of the negative interest, it gets an extra 100 instead of having to pay the liquidity pool. All 1100 coins go to the business. The business pays its workers as usual, but this time happily has a bit of a bonus left over, so it can sell those extra coins on TradeQwik to make some profit.

Thus it's clear that negative interest can be used by crownholders to increase the supply of VIVA coins, leading to more selling pressure and causing the price to drop if it rises too high.

Borrowing from the future

When the interest is negative, where do the extra coins come from? Remember that TRs don't allow mints to create coins for free; there's always a price to pay. Positive interest means that price is paid by mints to the liquidity pool (or more accurately, the pool owners). You might think that negative interest is the exact opposite: coins paid from the liquidity pool to the mint. But this isn't quite accurate. Keep in mind the liquidity pool does not actually hold VIVA. As all coins sent to it are destroyed, it can't directly pay the mints.

So what happens? Well, negative interest means the required fee is "borrowed" from the future holdings of whichever crownholder provided the mint's TR. The crownholder (or to be more precise, the VIVA Crown owned by the crownholder) becomes indebted to the liquidity pool and must settle that debt, either right away or at some future date.

Let's go back to the example of minting 1000 VIVA coins at -10% interest. Furthermore, imagine the mint's TR was obtained from our hypothetical Crownholder Bob, who currently owns a 44% stake in the liquidity pool from previously sinking his TR into it. This makes Bob responsible for settling the 100 VIVA coins required for the interest. The liquidity pool will automatically settle this debt for him by reducing his ownership of the pool, as if he had sent 100 less VIVA to it over the course of his lifetime pool contributions. Instead of 44% ownership, suddenly he's got 41.9%. Note that the percentages allocated to other pool owners will go up to compensate.

Figure 6: businesses are very happy; crownholders feel the pain

Crownholders have enormous power and ability to acquire large liquidity pool stakes through their TRs. But that power is offset by great responsibility: they are the ones who must carry the burden of absorbing negative interest by shrinking their stakes.

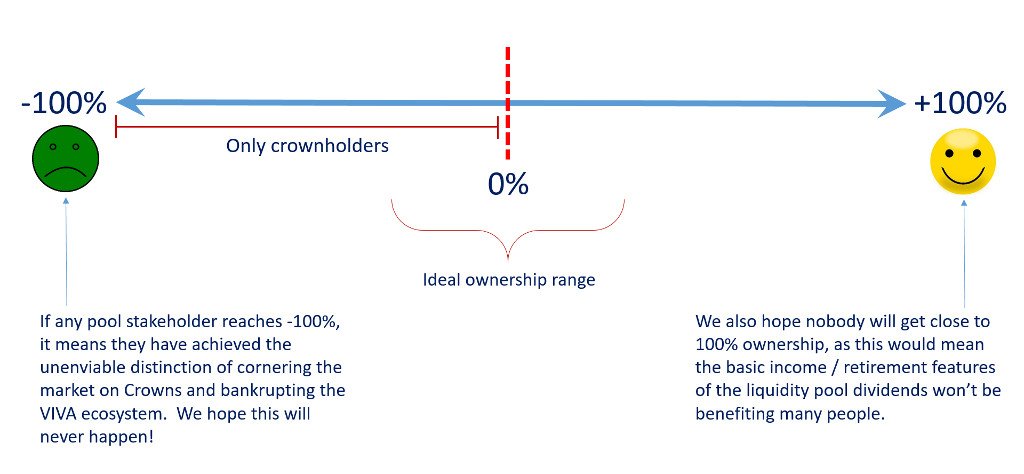

Negative stakes

If Crownholder Bob is a responsible crownholder, he will have built up a "buffer" over time to protect against prolonged periods of negative interest rates, by repeatedly sinking TRs into the liquidity pool. But what if he doesn't? What if he always rents TRs to a mint and has an empty liquidity pool account?

In that case, to satisfy the debt obligations of negative interest, Bob's stake will become negative. This is what's really meant by the phrase "borrowing from the future", in practical terms.

A crownholder with negative stake is unable to rent out TRs to mints until such time as the stake becomes positive again. Until then, Bob has to sink his TR into the liquidity pool and is forced to leave it there. This will gradually increase his percentage of the pool ownership every 90 days, until eventually it is positive again.

From this we can see that it's literally impossible for a crownholder to default on his debt obligations to the liquidity pool; Bob will simply be forced to leave his TR in the pool for as long as it takes.

So a person's liquidity pool ownership percentage can range from -100% to +100%. But only crownholders can have negative ownership, as only they are required to take on the debt burdens of mints.

Figure 7: the sliding scale of liquidity pool ownership

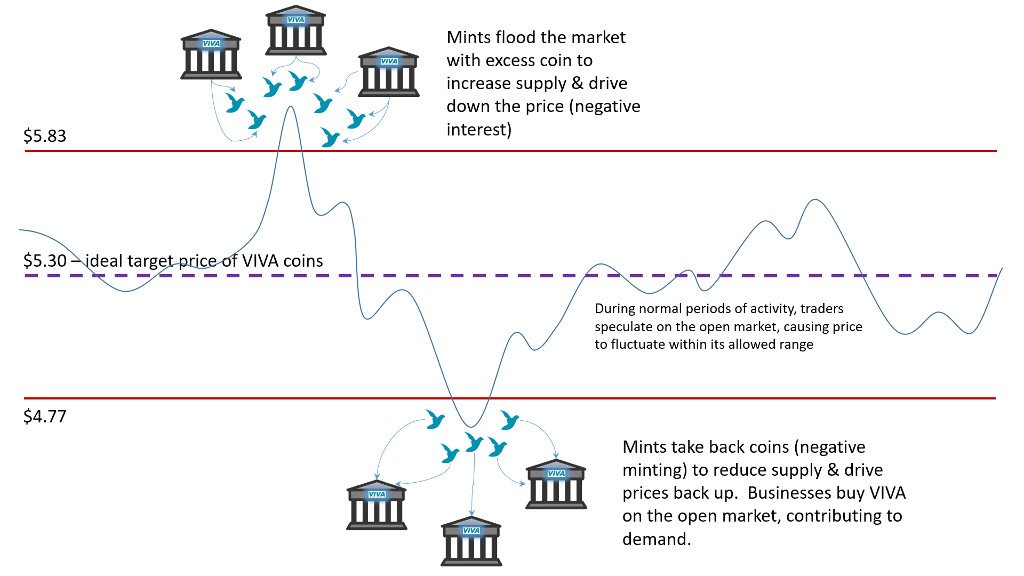

Keeping the price of VIVA stable

The target price of VIVA coins will initially be $5.30 per coin. They are designed to be price stable, but allowed to fluctuate freely on the open market within a 10% range of the target price.

So how is the price kept within this range? What happens when buyers or sellers push the price outside the range? Well, we've already seen that mint interest rates can be used to increase or decrease supply depending on the situation. If price rises too high, mints are temporarily allowed to create extra coins via negative interest, which are then sold on TradeQwik. This increases the supply to soak up the excess demand and pushes the price back down again.

Conversely, if price drops too low, then a period of negative minting ensues. Mints stop producing new coins, and instead take them back from businesses, which in turn are forced to buy VIVA on the open market to fulfill salary obligations to their worker nodes. This decreases the available supply and increases demand until the price goes back up.

Figure 8: VIVA coins are a price stable currency

In conclusion

I'll stop there for now. Writing this has helped me gain a deeper understanding of the VIVA system, and I'm looking forward to seeing the finished whitepaper. For any general readers out there, I'll remind you that the above content may have conceptual errors, and if so I'll try to correct them as soon as @williambanks corrects me.

It's worth pointing out that all the clip art I used in the diagrams comes from Pixabay and can be freely used for commercial purposes under the terms of Creative Commons CC0.

Links for further study

Here is a great collection of resources from @williambanks . If you don't know much about VIVA, these posts will fill you in.

Read about the whitepaper contest here (there is still time if you want to enter the contest yourself!): @vivacoin/viva-contest-so-you-think-you-can-graphic-artz

VIVA essential references:

- Part 1 - Introduction to VIVA : A Price Stable Crypto Currency with Basic Income

- Part 2 - More than meets the eye

- Part 3 - How does it work?

- Part 4 - How do you bootstrap a new economy?

- Part 5 - VIVA CAN? You bet!

Join the VIVA community chat: https://chat.vivaco.in

For more posts about cryptocurrency, finance, travels in Japan, and my journey to escape corporate slavery, please follow me: @cryptomancer

Image credits: VIVA logo used in the title image & diagrams is the original creation of the VIVA team. All other clip art comes from Pixabay and is used under Creative Commons CC0. The diagrams themselves are my own creation, built using Microsoft PowerPoint.

Achievement badges courtesy of @elyaque . Want your own? Check out his blog.