When Kurt Vonnegut Jr. (1922–2007) was 22, he’d no idea what to do with his life or even if he was a good writer.

After surviving the firebombing of Dresden, he served for the US army as clerk in in Fort Riley, Kansas.

Like many aspiring writers, he mulled about his future, success sand his craft. Vonnegut wrote to his wife about his career aspirations, Jane:

“Rich man, poor man, beggar man, thief; Doctor, Lawyer, Merchant, Chief.”

She didn’t have much time for Kurt’s self-doubt.

Jane believed Kurt would become a successful author, and she encouraged him to study great books like War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy and The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

She told him to write too.

Her faith surprised Kurt. In 1945, he wrote to her:

“You scare me when you say that I am going to create the literature of 1945 onwards and upwards.”

And yet, this young writer from Indiana listened to his wife, to his first muse. He stuck with his craft, going on to publish fourteen novels, five plays, three short story collections, and five works of non-fiction.

He even mined his experiences at Dresden to write the satirical, best-selling novel Slaughterhouse-Five.

In other words, Kurt got over his fears about becoming an author. He learnt how to write great books… and how to sell them.

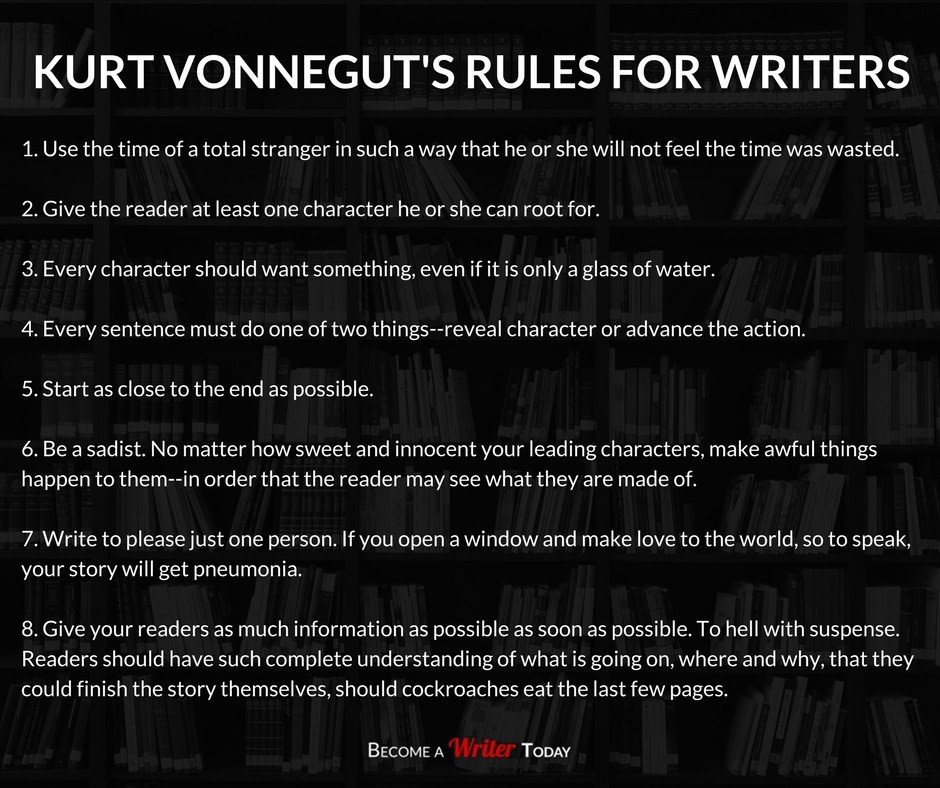

He also crafted eight rules for struggling and fearful writers… but they apply to all types of writing, even if you’re crafting the copy for the back of a cereal box.

Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Rules for Writers

It’s one thing to know something, but putting what you know into practice is a challenge. So let’s say you want to write a non-fiction book.

Well, how can you apply Kurt Vonnegut’s rules for writers?

Rule 1: Use the Time of a Total Stranger in Such a Way That He or She Will Not Feel the Time Was Wasted

The expectations non-fiction book readers differ wildly from book to book.

For example, if you’re writing for a niche audience, like long-distance runners, these readers want you to be ultra-specific. They expect detailed training plans and advice they can relate to.

I know figuring out what total strangers want is tough.

When you’re new at writing a book, the muse is a total stranger. You have to invite her into your home, sit down, pour her a warm drink and find out what she has to say.

She hates time wasters, and she’s not interested in silly questions either.

You know the ones:

- What should I do with my life (the question Kurt asked his wife)?

- Do I have the right tools to write?

- What will my friends and family think about this?

- Am I good enough yet?

- What about this idea? Or this one?

- Should I sharpen my pencils one more time?

Please. Stay focused.

If you ask those questions, the muse will grab her coat, throw her drink down the sink and walk out your front door. So rather than procrastinating about writing (because that’s what you’re doing) listen to the muse… and then get started.

Rule 2: Give the Reader at Least One Character He or She Can Root For

Who is the hero of your book?Successful fiction writers always give the reader a character we can root for. They gave us a Billy Pilgrim (Slaughterhouse-Five). They gave us a Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom (The Rabbit, Run Series by John Updike). They gave us a Harry Potter.

As a non-fiction writer, these leading characters include your readers, your subject.. and you.

Present your readers as the hero of your book by interviewing them or by telling the stories of their journeys throughout your book.

You could use their real-words and experiences to back up key points or to illustrate examples. This type of research will lend extra credibility to your book.

Your subject could be a historical or famous figure, whose life and learnings you draw upon as part of your research.

Rather than imparting information about a Thomas Jefferson or a Nelson Mandella-type figure, distil their life lessons into relevant stories for your book.

You can put yourself forward as the hero of the story (or even as the villain) by writing about your life and experiences.

YOU are the hero of this article, and I want you to root for yourself and your book.

Rule 3: Every Character Should Want Something, Even If It Is Only a Glass of Water

One hundred thousand readers, flat-screen televisions, inner peace… we all want things.

Your readers want deep and honest personal stories, your best ideas, a stern talking to, their problems solved or maybe they just want a damn good time… and it’s your job to give it to them.

In The 4-Hour Work Week, author Tim Ferriss explains how readers can achieve more by hacking and outsourcing their lives. He writes for readers who want to spend less time working and get more value from their free hours.

At the start of the book, The Year of Magical Thinking author Joan Didion wants her recently deceased husband John Gregory Dunne to return. Later, she wants a way of making sense of her grief.

In The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell wants his ideal reader to understand how little things like the Pareto Principle (20% of your work equates to 80% of the results) make a big difference.

If your book is going to help your readers, you can write about how they can run 26.2 miles, travel around the world on ten dollars a day, quit smoking, have a ten-minute orgasm and so on.

Rule 4: Every Sentence Must Do One of Two Things–Reveal Character or Advance the Action

I hate it when writers push towards their big idea with the speed of a tortoise on valium. They ask the reader to wade through page of obscure, bland writing like:

- In this chapter, I will show you…

- There are serious issues that will need to be carefully and closely addressed in great detail…

- After careful consideration of all the facts…

- It’s become painfully apparent to me that…

- In summary, I draw your attention to…

Kurt would tell you not to be a barbarian about it. By all means, lay out your pitch in your book’s introduction, but then get to it. We don’t want an instruction manual or a legalese document that takes a PhD to decipher.

Be insanely practical or alarmingly entertaining.

While editing your book, ask, what can you cut? What should you take out? I ask because your muse is putting her coat on.

Don’t worry. I’ll cover self-editing your book later on (oh God, did I just clear my throat?).

For now, know that every word, sentence, paragraph and chapter should advance your book’s story or controlling idea. With clarity, precision and speed.

Anything else belongs in the trash can.

Rule 5: Start As Close to the End As Possible

Spotify, Netflix, YouTube, Facebook, Amazon, Google… if you want to capture and keep your reader’s attention (and sell copies of your book), you’ve got competition.

In the first few pages of your book, put your reader through hell and then take them to heaven.

Are they trying to stub out the cigarettes once and for all? Do they want to create an exercise routine that gives them washboard abs? Are they [lacking motivation](@bryancollins/the-secret-to-feeling-motivated?

Well, consider what their life looks like now and how far they must travel.

Then, tease a picture of your reader’s ideal world, of healthy lungs that can power a four-minute mile or those abs you could chop carrots on.

Neil Strauss doesn’t hold back in his bookDo it all before page 50, and spend the rest of your book showing your reader how to get there.

If your book isn’t going to reveal the how, then entertain the hell out of your readers through storytelling.

For example, in The Truth, New York Times best-selling author Neil Strauss writes in painful detail about his entertaining and prolific sex-life alongside his theories about romantic relationships.

It’s not a how-to manual for the brokenhearted, but it’s a damn good read.

Rule 6: Be a Sadist. No Matter How Sweet and Innocent Your Leading Characters, Make Awful Things Happen to Them–in Order That the Reader May See What They Are Made Of

Let’s say you’re writing a self-help or a business non-fiction book.

Your ideal reader possesses a specific problem they need help solving. They want to quit smoking, lose weight or finally master the cash flow of their business and so on. But, they don’t understand their problem entirely.

You should.

You’ve spent hundreds of hours studying their problems from every angle, and you’re about to report back on what you discovered.

So, start by writing about your ideal reader’s pain-points and what keeps them up at night, by drawing on his or her experiences through your research.

Be intensely curious.

What will happen if they don’t lose weight, quit smoking or take charge of their cash flow?

Throughout your book, point to case studies and stories. Provide practical exercises or takeaways so your readers can put your ideas into practice and see what they’re made of.

In your case, share messy and uncomfortable stories from your personal or professional life, the ones where you don’t come out on top. Sure success is sweet, but it’s boring. We want to hear about plans gone awry and what you did next.

Rule 7: Write to Please Just One Person. If You Open a Window and Make Love to the World, so to Speak, Your Story Will Get Pneumonia

Do you know who your ideal reader is, what they read or even dream of?

If you don’t, find an ideal reader and talk to him or her. They could be in your creative writing a group, a reader of your blog, a colleague or even a close friend.

Interview them. Show them early drafts of your chapters. Crawl inside their head, and take notes until you understand what they expect from books like yours.

This article is for aspiring authors who want to learn how to write a non-fiction book. The advice and stories I include here won’t please advanced authors because they understand how to write a book. Similarly, aspiring fiction writers may wonder ‘What’s in this book for me?’

However, if I tried to write for these audiences too, I’d have to open the window and let in more ideas, angles, stories and writing advice for all types of people. And my book would get pneumonia.

Now, is your book catching a chill?

Rule 8: Give Your Readers As Much Information As Possible As Soon As Possible. To Hell With Suspense. Readers Should Have Such Complete Understanding of What Is Going on, Where and Why, That They Could Finish the Story Themselves, Should Cockroaches Eat the Last Few Pages

Unless your name is James Joyce and Ulysses is your game, your readers should understand what you’re writing about. Break down the complicated topics underpinning your book using everyday language.

While information is nice, eliminate jargon, qualifiers and unnecessary disclaimers.

Use words your readers know.

Speak, as if, this book is for a friend. When your readers reach The END, they either have all they need to solve their problems…. or they enjoyed themselves.

I write practical and conversational non-fiction, wherein I explain everything the reader needs to know about a particular topic. If the reader gets confused, I’m not doing my job.

You too must read up on your topic. Look for ideas in the books you read, in the people you meet and in the backstory of your life.

Combine your research in interesting and exciting ways. Then, when you sit down to write, remember to serve your readers. Don’t hold anything back, hide or look away.

By the time you’re through, your readers should know what they need to do next and feel excited about doing it. Or, they should have had a damn good time. Help them make a habit of it.

Understanding Great Writing… Just Like Kurt Vonnegut

During the mid-1960s, after Vonnegut became a successful novelist, he taught his craft at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop.

His writing advice, much like his books, possessed unusual quirks. He told aspiring authors to consider six stories they liked and disliked as if they’d “just consumed two ounces of very good booze”.

Then, he asked them to rewrite the table of contents of these stories on a blank page and grade each chapter from A to F. Finally:

“Write a report on each to be submitted to a wise, respected, witty and world-weary superior. Do not do so as an academic critic, nor as a person drunk on art, nor as a barbarian in the literary marketplace.

Do so as a sensitive person who has a few practical hunches about how stories can succeed or fail. Praise or damn as you please, but do so rather flatly, pragmatically, with cunning attention to annoying or gratifying details. Be yourself. Be unique. Be a good editor.

The Universe needs more good editors, God knows…

Do not bubble. Do not spin your wheels. Use words I know.”

Non-fiction writers too should evaluate stories they like and dislike.

Like the mechanic who takes apart an engine to understand how it works, this practice will help you understand how great writing succeeds and what rules you can break.

It will help write something readers can’t put down.

Did you enjoy this post? Please upvote.

Neil Strauss by Justin Hoch, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16675325