The more fantastic a story, the greater the need for justification. To write a technothriller about a covert ops team hunting down terrorists, all you have to do is say that the government created new counterterrorist organisation with the best training and technology to pursue evildoers, and a reader will happily lap it up. But if a story has strong fantasy or sci fi elements, writers need to go out of their way to create a world where their story can plausibly take place.

Let's take the original Star Wars trilogy. The franchise rests on several core pillars: the Galactic Empire and the Rebel Alliance that opposes it; the existence of many alien species with roughly compatible biochemistry and language, terraformed worlds and faster-than-light spaceships; and most of all, the Force. Take any of these away and you won't have Jedi fighting Stormtroopers with super Force powers, Han Solo smuggling contraband across the galaxy, Jabba the Hutt taking Leia as a slave, the Death Star, or Ewoks.

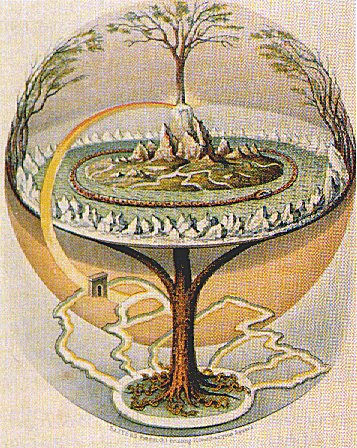

Worldbuilding goes more than just creating a cool setting and exotic societies. You are building the axes mundi, the world pillars, that make the story, characters, setting, and events possible. When done right, the worldbuilding enables spectacular stories and compelling characters to come to life. But when the worldbuilding is shaky and half-hearted, it undercuts the story it is meant to support.

Case in point: Talentless Nana.

How NOT to Create A Story

In the world of Talentless Nana, humans are under siege from an implacable enemy. Fifty years prior to the story, monstrous creatures with supernatural abilities began appearing around the world, leaving death and devastation in their wake. However, by some miracle, children also began developing psychic powers. Called Talented, they are treated as the saviours of humanity. The government of Japan identifies the Talented and sends them off to a special boarding school in an isolated island, where they learn how to fight the enemies of humanity.

Our hero is Nakajima Nanao, a young boy with no talent who was somehow admitted to the school, and is isolated from everyone else in class. In Chapter 1, a new student named Hiragi Nana transfers into the school. Hiragi is a perpetually cheerful telepath, and with her mind-reading powers she quickly neutralises the class bully, makes friends with Nakajima -- and draws out his hidden talent: the power to neutralise other talents. In an instant, Nakajima goes from outcast to hero.

As the chapter draws to a close, Nakajima meets Hiragi at an isolated cliff. They have a heart-to-heart chat, and Hiragi reveals she can't turn off her power. Nakajima holds her hands. Hiragi breaks into a grateful and bashful smile, and declares she can't read his mind. It's the perfect set-up for a confession.

And Hiragi pushes him off the cliff.

Surprise: Hiragi Nana is the Talentless Nana of the title.

In Chapter 2, we learn through Nana's flashbacks that the enemies of humanity are, in fact, the Talented. These superpowers turned the Talented into monsters, seeking to overthrow civilization. After five years, humanity wins the war against the Talented; a hundred years later, the Japanese government has somehow convinced the people that the 'enemies of humanity' are an alien species and that the Talented are humanity's last hope, so that the Talented children can be gathered on an island for Nana to quietly dispose of them.

There and then I dropped the manga.

If great powers lead to great madness, then there would be a perpetual pogrom against the Talented akin to Aktion T4, in which the Talented would be rounded up and either summarily executed or sent to extermination camps. If that were too distasteful or dangerous to do openly, the government can simply tell the public that the Talented children will be taken to a special facility where they can learn to control their powers, and quietly liquidate the Talented once they are out of the public eye. If the children must absolutely be concentrated in an isolated area, an easy method for extermination would be to simply firebomb the place from the air when it reaches critical mass. Or simply flood the dorms with poison gas.

There is no reason to insert a sociopathic Talentless teenager into the school simply to murder every single student.

And this isn't even going into what it takes to keep the cover-up going for fifty years: fake combat engagements, mocked-up monster corpses, pretend veterans of phony wars, a never-ending stream of corpses and cripples, the odd town destroyed or devastated by the monsters... In a world even remotely resembling ours, there is no way such a demanding cover-up could last for longer than a day.

It's clear that the mangaka simply wanted to create a story in which a sociopathic schoolgirl attempts to wipe out her supernaturally gifted classmates without getting caught, hooking the readers with a generic shounen main character who gets offed at the end of the first chapter for shock value. The worldbuilding is a flimsy fabrication that falls apart in the glare of critical thought. The insert about how the Talented become monsters is a lousy excuse to make the reader feel less outraged about the murders. Nothing in the worldbuilding justifies Nana's mission, since there are plenty of easier and more effective ways to kill all Talented. And if you follow the worldbuilding to its logical conclusion, it makes the story impossible!

The poor worldbuilding of Talentless Nana makes the story come off as cheap and shallow. It is edgy for the sake of being edgy, dark just because it wants to differentiate itself from the superhero crowd, and features a sociopathic schoolgirl as a main character just 'coz.

I've read speculations that this is just the set-up for a later plot twist. To whit, the government officials who sent Nana on her mission are, in fact, the true enemies of humanity, who want to use Nana to dispose of the Talented before they can pose a threat to their plans. Even if this were the author's true intent, this doesn't make sense.

The school is on an isolated island. It is quicker and easier to send an army of goons to destroy the school and everyone in it than to train and deploy a single sociopathic teenager. The Talented in the school are just children who haven't come into their full power; with enough manpower they can be killed with ease. Indeed, you could create a more compelling story by having Talentless Nana wage a guerilla war against an army of Talented mooks to save her classmates.

If brute force were not an option, then the plot twist must be foreshadowed as early as possible to tell the reader that he shouldn't completely trust the world pillars he's seen so far. This could be as subtle as a page showing a secret agent learning about Nana's mission and hinting that the organization that sent her is the enemy, or as dramatic as a teacher approaching Nana, telling her that he knows of her mission, and that the organization that sent her is the enemy. This reveals to the reader that Nana herself can't be relied upon to accurately convey the truth of the story world, leaving the reader wondering who is good and who is evil, which aspects of the revealed world can be believed, and eager to find more answers in the next issue.

How to Do Worldbuilding Right

By contrast, let's examine Boku no Hero Academia. This is set in a world where superpowers are common enough that superheroes and supervillains are everywhere. Superheroes run private companies contracted by local governments to handle crime and disasters in their local, and are adulated in the international media. Every child dreams to be a superhero, and those with superpowers join special schools to learn how to become superheroes. These core worldbuilding pillars don't just establish the mileu of the series: they make many intriguing story arcs and characters possible.

In the Sports Festival Arc, we learn that superheroes scout recruits by observing sport festivals at superhero academies. Among these superheroes is Endeavor, the world's second-greatest superhero. Unlike his rival All Might, who is the perfect exemplar of truth, justice and the American Way, Endeavor is a self-obssessed megalomaniac whose sole ambition in life is to upstage All Might and become the world's number one hero. Since he can't beat All Might fairly, Endeavor married a woman with a useful superpower to create a son with even greater powers, who he hopes will beat All Might.

The world doesn't know about this side to Endeavor. As far as the public knows, Endeavor is a hero of justice with an impeccable record of fighting villainy. At the time of writing, Endeavor's dark side has yet to be revealed to the public, showcasing the flaws of the world's superhero system.

The following story arc introduces Stain the Hero Killer. Stain, inspired by All Might, believes that only superheroes who fight for selfless reasons are worthy of being called heroes. Targeting heroes and villains alike, Stain tests his victims to see if they were true heroes in his estimation. Had Stain showed up earlier he would have been seen as a madman. But now that the reader knows the truth about Endeavor, Stain comes across as a byproduct of a system that rewards superheroes simply for using their powers in an approved fashion instead of being paragons of virtue. Indeed, Stain's ideology may even make a twisted kind of sense. At the end of the arc, when protagonist Midoriya Izuku takes down Stain, Midoriya must hide the truth, for as a junior Hero he could not use his powers without the permission of a guardian -- so the credit for Stain's arrest goes to the nearest licensed superhero on the scene: Endeavor.

The worldbuilding of Boku no Hero Academia didn't simply create a static playground for the author to create fantastic tales; it set up characters and story arcs like these, allowing characters to reveal their true natures, and explore through their deeds the ramifications of a society built on superpowers. In doing so, the story shows gives the reader an opportunity to ponder about the true meaning of justice in such a world and what it means to be a hero, adding breadth and depth to the series.

The Heart of the Story

Effective worldbuilding allow the reader to suspend disbelief and engage the story entirely. At the highest levels of storytelling, worldbuilding grants the author the tools to create compelling tales that surprise the reader, add breadth and depth to the world, and set the stage for even more stories to come.

Consequently, worldbuilding must be performed with great care. As in the case of Talentless Nana, careless worldbuilding can effectively undermine your entire story. This leaves the reader feeling that all you have is a cool premise executed by idiots, with little to back it up.

Worldbuilding is the art of building the axes mundi of the world in which the story resides. Stories with strong axes have a great advantage over others -- stories with weak pillars must collapse.

Image: English translation of Poetic Edda, Oluf Olufsen Bagge, 1847. First found on Wikimedia.

Unlike Talentless Nana, my own novel No Gods, Only Daimons has been consistently praised for its intricate, unique and enthralling worldbuilding. You can find it on Amazon here.