10,000 Years of Strangeness: A Paranormal Primer for Ancient and Modern China

Part III: Mysteries and Legends

Chapter 11: The Insecto-Reptoid Heads of Sanxingdui. 11-2: Lost City Found.—三星堆的昆虫爬虫类的头. 失落的城市再现

Chapter 11: The Insecto-Reptoid Heads of Sanxingdui. 11-2: Lost City Found.—三星堆的昆虫爬虫类的头. 失落的城市再现

Previous Chapters 前章: Part 1: Chapter 1, Ch 2, Ch 3, Ch 4, Ch 5-1, Ch 5-2, Ch 5-3, Ch. 6

Previous Chapters 前章: Part 2: Chapter 7, Ch 8-1, Ch 8-2, Ch 8-3, Ch 8-4, Ch 8-5, Ch 9

Previous Chapters 前章: Part 3: Chapter 10, Chapter 11-1

Previous Chapters 前章: Part 3: Chapter 10, Chapter 11-1

Exactly three street vendors were firing up their carts and serving noodles and bing (饼) to the tourists, while a fourth sold watermelons out of a ‘pick-up trike,’ a kind of three-wheeled motorcycle with a cargo bed over the rear wheels.

There was a big sign with “Birds to Look For.” It pictured some common birds of the area with their Chinese and English names. There were two that I’d never seen before and decided I’d try to get them on ‘the list’ while we toured the park. They were the grey-headed greenfinch (grey-capped in most English sources) and the black-throated tit. In reality, I don’t keep an actual list like most birders. It just isn’t Zen.

Many mysterious places exist in the myths of Mankind. These places are known only from the myths that record them: Atlantis (亚特兰提斯岛), Shambhala (香巴拉), Camelot (卡麦勒).

Both myth lovers and scholars alike become so enchanted with these tales they imagine these places must exist, or must have existed, somewhere. Certain myths just play in our minds and touch us so deeply that they must be real, or so they seem. And every now and again they are. Heinrich Schliemann did find Troy (特洛伊). Juris Zarins did find the lost city of Ubar. Helike, Heracleion, Urkesh, La Ciudad Blanca, and Musasir have all emerged from the jungles, sands and seas of the world.

For hundreds of years historians pondered over the ancient Kingdom of Shu (蜀). It was known only from ancient texts like Records of the Grand Historian, or Shiji (史记) in Chinese, and Book of Documents or Shujing (书经), but there was no physical evidence that any such Kingdom or culture existed. Ancient historians in China, like the authors of the aforementioned books, sometimes depended on legend or unreliable sources and then recorded them as fact thousands of years after the fact. It was therefore thought for centuries that the Kingdom of Shu was merely a legend, a myth, a mix of fact and fiction at best, not unlike Plato’s chronicling of Atlantis.

The first clue that it might have been real came in 1929 when farmers digging a well in the Chengdu Plain of Sichuan Province found a stash of jade artifacts that eventually were sold off to private collectors. Their true historical significance may never be known. However, archaeologists became interested and combed the region around the city of Guanghan for further discoveries. Otherwise, it was completely forgotten by the rest of the world.

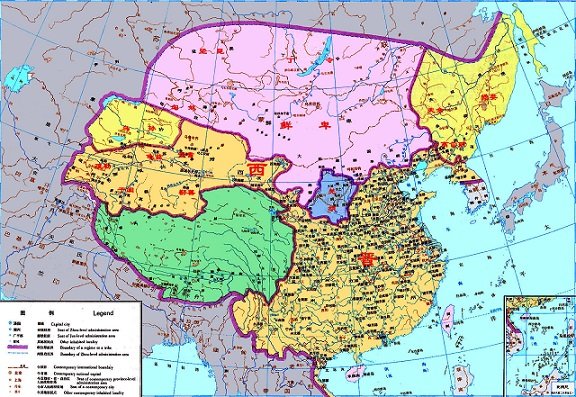

The Chengdu Plain was isolated from ancient China by the Qinling Mountains. What we call China today was a much smaller place thousands of years ago. While the Chinese can boast the oldest continuous culture on earth, they cannot accurately boast the oldest nation. The region known as China is actually home to 55 native ethnic groups, only one of which, the Han, is Chinese as Westerners think of it. The others had their own kingdoms and tribal territories throughout the long history of China. Furthermore, the Han themselves were broken into various countries and warring kingdoms as well. This is why you have the Warring States period, the Three Kingdoms, and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. On the Chengdu Plain the Shu (蜀) culture forged its own Kingdom and its own history in isolation from the Han dynasties to the North, vanishing into the mists of legend 3000 years ago.

Then, in 1986, as is so often the case with important archaeological finds, the site at Sanxingdui was discovered completely by accident when workers unearthed two sacrificial pits filled with jade, bronze, and clay artifacts, in exactly the right location for the legendary Kingdom of Shu! If this were indeed the case, the entire cultural history of China would have to be reconsidered. To put it in perspective, it would be like archaeologists in the Middle East confirming the existence of the Nephilim from the Bible by unearthing an ancient city of giants, thus rewriting the history of Western civilization and the human species.

In the months following the 1986 discovery, over 1200 artifacts were unearthed in what was one of the most important archaeological finds of the 20th Century. And yet, much remains unknown about the Sanxingdui culture. Why did they disappear? Why did they make these artifacts? Why did they sacrifice them? What was their political and religious system? No written language connected with them has yet been found, so virtually everything we believe about these people has been deduced by archaeologists studying the find, and minds of modern people always see things differently than the ancients.

The grounds at the archaeological park are beautifully landscaped. It was as if we were strolling around the National Arboretum in Washington, DC, or Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania. Sure they didn’t have the specimen plantings those places have, but the setting was reminiscent of them. Outsiders often poo-poo public exhibits in China as second class or worse. They’re often unkempt, dark and litter-strewn. Not this place. It is spotlessly clean, well-maintained, thoroughly interesting, and the gardens and paths are soothing and revitalizing.

Sanxingdui is first rate as soon as you enter it with superb English signage for international visitors. Even the explanatory plaques in the museum have good, accurate English. A topnotch effort clearly went into planning and installing this place. The only thing it really lacked was decent food. I recommend bringing a picnic lunch to enjoy on the beautiful, quiet grounds filled with birdsong.

There are three large exhibit halls set up in separate buildings filled with hundreds of artifacts. Entering these buildings is immediately like entering a dreamscape. They are dimly lit in otherworldly reds and blues. Only the exhibit cases are well illuminated. Visiting the halls is like drifting transcendentally from case to case to gaze upon and marvel at the mysteries therein. As you complete one dream, you wander out into the brightly lit daylight world of birdsong and flowers and make your way to the next hall of dreams of ancient treasures.

Although there are hundreds of artifacts on display, the two types that strike you most are the jades and bronzes. To me, the mystery of the Sanxingdui centers on these two things.

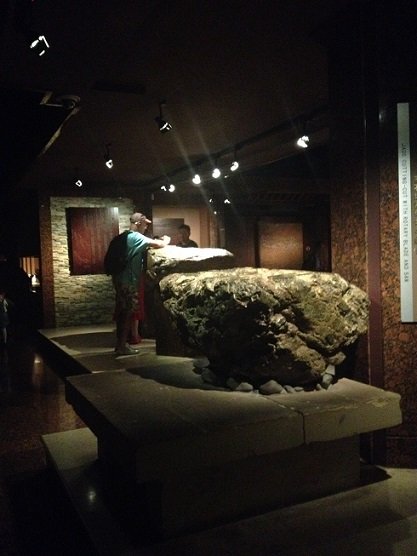

Drifting from the pottery exhibits and entering the exhibit room with the jade, the first piece you see is a huge cubic boulder of jade about the size of an old 20-inch screen television with clearly worked smooth surfaces on some of the protuberances. Just beyond this are more huge blocks of jade, all fairly cubic boulders. Unlike most museums in the West, here you can step right up to the jade, examine it closely and even touch it. My first impression on seeing these rocks from the early Bronze Age, Bronze Age mind you, it that they looked as if they’d been cut with a circular saw!

I bent over these stones, squatted and kneeled with my bum knee, got up close and felt the marks, and lo and behold, the marks had to be from a circular saw. I have cut both wood and stone with circular saws and know exactly the tell-tale signs. When the cut is finished, it leaves a series of arcs on both pieces. If the saw is dull or moves too slowly, the marks will be more pronounced, and with wood it will even burn. If a cut is not completed, it will leave a distinct uniform groove the width of the blade as far as the blade went. The unfinished cut leaves the uncut portion hanging from the main piece.

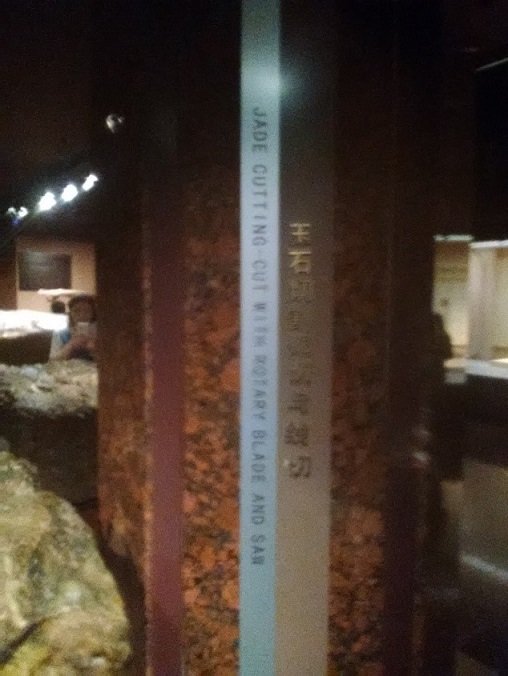

I saw all of these tell-tale signs in the jade blocks, even portions where the blade had been used to cut off portions of stone and penetrated protuberances leaving the telltale grooves of incomplete cuts. But jade is harder than bronze on the Mohs scale. So how did they cut the jade with bronze blades? How the Hell did they make a circular saw to begin with over 3000 years ago? I thought “maybe I’m wrong,” but as I came around the end of the exhibit, there was a column, next to a big chunk of jade with a vertical sign in English and Chinese: “Jade cutting—cut with rotary blade and saw.” So my conclusion was the same as the archaeologists!

This presents a compelling mystery. How did these ancient people make circular saws (or rotary saws as the museum sign puts it)? Many enthusiasts of ancient mysteries will jump to the conclusion that space aliens must have done it. That’s pretty unlikely. To begin with, if it is true, where are the circular saws the “aliens” used? Secondly, why would space aliens, capable of traversing space and time, use some kind of primitive power saw to cut stone when surely they had more powerful means at their disposal? But what if the Sanxingdui were very ingenious people as many of these artifacts indicate they were? How could they have made a circular saw capable of cutting jade 3000 years ago and power it without electricity? Now you’re getting into some good nuts and bolts problem solving instead of vaguely passing it off to some unproven ancient space travelers.

For example, is it possible to shape a proper circular saw blade out of bronze to get an efficiently cutting saw? How long would it take to make the cuts seen in the stones? How much pressure would have to be applied to the cutting edge? How many rpms would be required for the saw to be effective? How could you achieve that pressure? How would you power the saw? By hand? By foot? With animals? With a water mill? How would you cool the cutting edge? By hand pouring water? Or by trickling water through a channel or tube? These are intriguing experiments that can be performed and tested. Unfortunately I do not have the resources to be casting bronze into disposable saw blades, but someone does.

If bronze doesn’t work, then what other material can be used? Was it a combination of techniques, only one of which was a circular saw, the one that left the most distinguishing marks behind? All of these options need to be explored before invoking any kind of supernatural or extraterrestrial explanation.

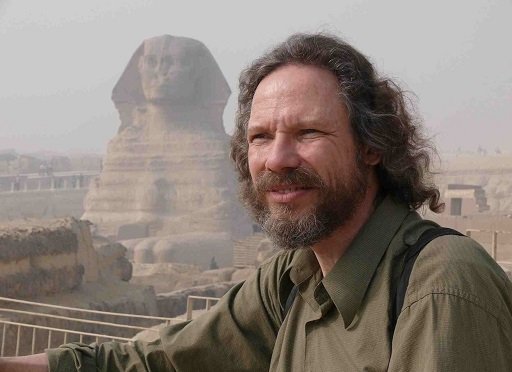

Christopher Dunn, a machinist who does advanced work on aerospace tooling and defense contracting, also found baffling signs in Egyptian artifacts that obviously had not been noticed, or perhaps ignored, by Egyptologists. Sometimes it just takes an engineer or skilled craftsperson to see things that archaeologists, anthropologists and historians aren’t trained to see. You’d think they’d at least be trained to invite pertinent experts outside their disciplines to examine important things like architecture, construction techniques, tool marks and so forth, but they don’t. And instead of being thankful for the Chris Dunns of the world who do notice them and seek to advance our knowledge of places like ancient Egypt, they are rejected and ridiculed as cranks because Egyptologists are arrogant and small-minded people.

Just look at how they responded to a real scientist, geologist Robert Schoch, who, using the real science of geology proved that the ancient Egyptians could not have carved the sphynx because the water erosion proved it predated the Egyptians by thousands of years. Today, nobody accepts that the Egyptians carved the sphynx, except Egyptologists. Who are these posers that go into Egyptology anyway, showing off as if they were actual scientists. That is the topic of a whole other book.

Back to Chris Dunn. He noticed anomalies in many Egyptian artifacts from drill holes, to precise measurements, to tool marks, and concluded that the tools that made them were not present in the archaeological record. So what tools did do it? We don’t know, they’re not in the record. And that is an honest and fair scientific position. Further research may yield results. And so it is with the cut jade at Sanxingdui, the saw is not in the record. If it has turned up elsewhere since, there is no mention of it at Sanxingdui and so remains a compelling mystery.

But if unknown rock-cutting abilities aren’t enough to get you speculating about space aliens, perhaps the strange bronze insecto-reptoid heads that are the signature and most distinctive work of the Sanxingdui are.

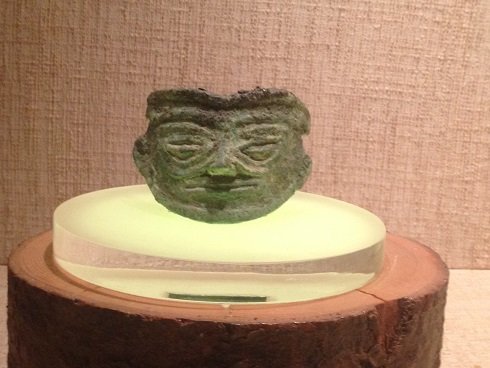

Legend has it that the founder of the ancient Kingdom of Shu, Can Cong (蚕丛), had protruding eyes. If the eyes in the mask pictured below are any indication, he was practically part insect.

Exaggerated eyes and ears became a hallmark of Sanxingdui bronze masks, but unlike the stalked eyes of the enormous mask, the others were more, well, reptile like. Throughout the exhibits these masks smile eerily at you from their displays. It is not ironic that the Chinese character for insect, 虫, appears in both Can Cong’s name and the word for Shu—蜀. Pre-tay innnteresting.

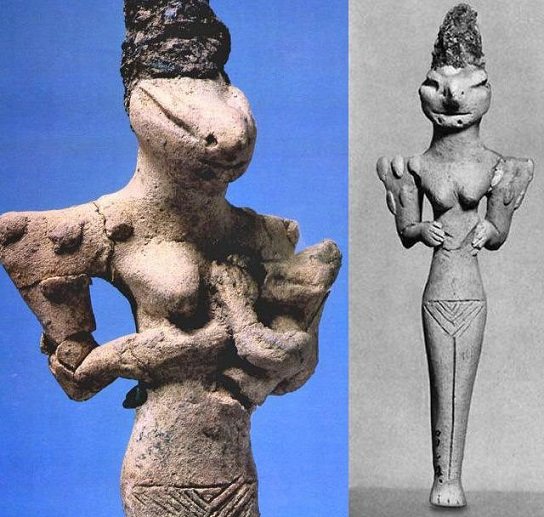

When compared to some of these other ancient sculptures, the similarities are obvious, especially the oversized eyes, their shape and the slits.

In fact, as you browse the collection of masks, it strikes you that none of them represent realistic human proportions. Certainly the artisans who made them had the skill to do so if they had wished. So why didn’t they?

One of the most astonishing bits of craftsmanship can be seen in the figure that tops this sacrificial ziggurat. From a distance it looks like some kind of monster-like god looming over his craven subjects. Note the intricate work on the teeth in its double trapezoid head, the flames shooting out of its nose, the stalked eyes. It’s broad, oddly shaped arms hang at its sides, and its knees have wings. What bizarre creature is depicted in this towering, domineering figure?

Upon closer inspection we discover that the teeth are made of people. (Soilent green is people! Soilent green is people!) Its eyes are birds! Its nose is the face of a humanoid, and its arms are the tails of birds.

Who is this ghastly figure and why does he loom so menacingly over his worshipers? We will probably never know. The Sanxingdui left no written account of their culture. Aside from the scant mentions in ancient chronicles, almost everything that is known about them comes from the sacrificial pits from which the artifacts that fill these exhibits came. Unfortunately, although the pits are generally open to the public, they were closed the day we were there.

In many ancient cultures there are stories of bizarre human hybrids. The Greeks gave us the Minotaur, a half man half bull beast that feasted on human flesh in the heart of the Labyrinth. According to the myths, King Minos’ wife Pasiphae fell in love with an enchanted bull sent by Poseidon and had a child with it. The Minotaur was their hideous offspring. The king hid it away in a labyrinth and every year sent it 14 Athenian youths to feast on until it was slain by Theseus.

The Bible tells us of the Nephilim, giants that were the offspring of “the sons of God” and the “daughters of men.” The last of these Nephilim may have been Goliath, the infamous Philistine giant that was slain by the young David during the conquest of Canaan.

Of course, not all hybrids turn out to be villains. Hercules was half, god half man. By performing the 12 works of Hercules he became what is probably the greatest hero of the Classical world. Other demigods went on to be heroes who served humanity. Perseus, son of Danae and Zeus, beheaded the Gorgon. Theseus who slew the Minotaur was the son of Aethra and two fathers, one of which was Poseidon. Zhu Bajie (猪八戒) was a pig-human-god hybrid in ancient China that went on to become a priest initiated by the goddess Guan Yin herself.

The ancient world was full of animal-human and god-human hybrids. Even today, scientists studying ancient human DNA have stumbled on surprising finds that indicate some kind of hybridization was going on in the ancient and prehistoric worlds. The mummy of Akhenaten has turned up some very curious and inexplicable genetics. In Central Asia there appears to have been rampant hanky-panky going on between various species of hominids in the area.

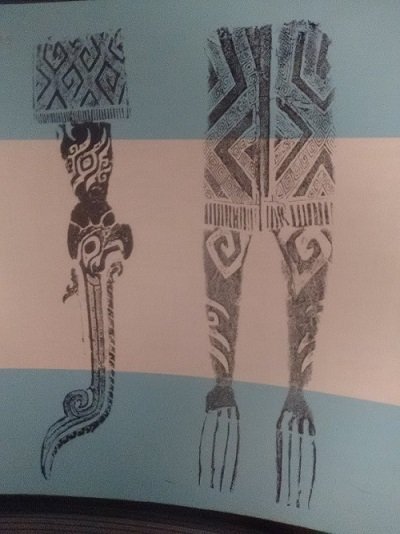

In Sanxingdui, the favored hybrid seems to have been bird-human. Above, we saw the double trapezoid-headed god towering over his minions with birds for eyes and arms. Elsewhere in the artifact collection we see “bird-men”, but unlike the Egyptians and Sumerians who gave their gods bird heads, the Sanxingdui gave them bird feet. In fact, the Sanxingdui seemed to have a fascination with birds in general with many of the bronze and pottery artifacts featuring birds, bird feet or bird heads.

It is said that Can Cong with his stalk-like eyes ruled the ancient Kingdom of Shu for several hundred years (not unlike the extended lifespans in the Old Testament, ancient Sumerian chronicles, or out old friend Zhang San Feng from Wudang Mountain). This would have lasted through the eras in Chinese history known as the Xia, Shang and early Zhou dynasties, a period lasting from 1700-1000 BC! During that time he taught them how to raise silk worms and make silk. He often toured the kingdom to check on its progress in a blue-green (or is it green-blue? I’ve never been sure exactly what color qing is) robe, leading to him being referred to as the god of the blue-green robe (青衣神, qingyi shen, literally “blue-green clothes god”).

And speaking of bird men and gods, I did in fact see the grey-capped greenfinch, lots of them, but never glimpsed the black-throated tit. I made up for it the following day at the Panda Reserve by spotting plenty of them and a red-billed leiothrix (红嘴相思鸟).