Here I present some evidence whether there is a relationship between fear of indebtedness and the socio-economic level of the prospective students’ families; whether there is an association between fear of indebtedness and students’ performance; whether there is a link between fear of indebtedness and the type of post-secondary courses that students study.

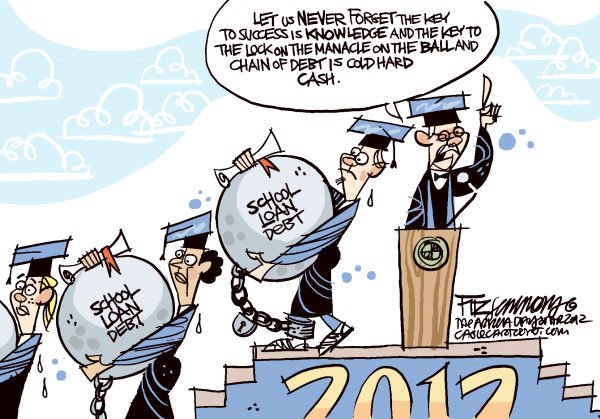

Throughout this review, "fear of indebtedness’ has been understood to refer to the perception of young people and their families that the decision to go on to Higher Education will entail assuming a level of indebtedness that would be difficult or nearly impossible to manage in the future.

The Status of the Debate

Higher education policies have considered increasing the availability of loans so that the different socio-economic strata can have a more equal access to Higher Education.

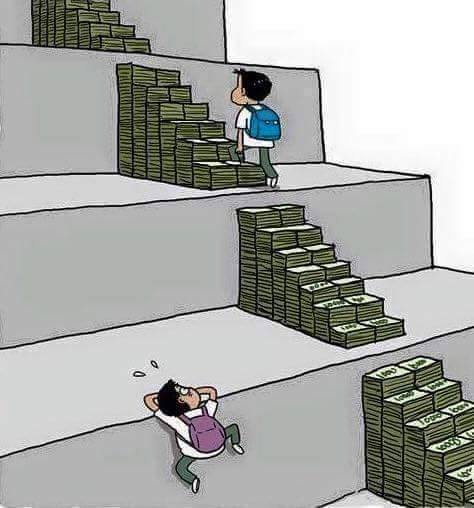

In this context, Carneiro and Heckman (2002) have analyzed the relationship between family income and access to Higher Education, focusing on short-term loan restrictions and long-term factors that permit the development of cognitive and non-cognitive skills. They argue that long-term factors which foster the previously mentioned skills are the principal determinant in the relationship between family income and access to Higher Education, as “Children from families with higher incomes have access to resources that children from families with lower incomes do not have” (p. 708). Still, they also remark that credit restrictions do not affect the decision to enter into Higher Education, given that these restrictions are overcome by Higher Education students by their becoming involved in paid work (p. 731).

The results reported by Carneiro and Heckman, show that a policy giving universal access to student loans for Higher Education does not necessarily imply an increase in access for those from disadvantaged sectors. Those authors provided with significant and interesting evidence with respect to the availability of loans, but a matter of utmost importance in this discussion is the predisposition that different income levels have to become indebted in order to study.

Are you willing to be indebted for the rest of your life or for a long period to attain a college degree?

The effect that fear of indebtedness has on access to Higher Education has been analyzed in Great Britain by Claire Callender (2002; 2003; 2005; 2008; 2017) focusing on the progressiveness of the system and on whether it facilitated access, particularly amongst the more disadvantaged sectors. Callender’s findings indicate that young people from lower income backgrounds have a greater aversion to indebtedness and that they are far more likely to decide not to continue their studies on to Higher Education for fear of indebtedness.

Those studies also showed that students who were poor before entering Higher Education and those from disadvantaged homes were the ones that accumulated the most debt.

Studies carried out in the United States show that be a student from a low-income home is associated with a lower likelihood of completing their studies, and that those who complete them are less likely to have good academic performance and to find a job after graduation (Mumper and Vander Ark 1991). In parallel with the above, research by Elias and others (1999) about the United Kingdom concluded that students belonging to the poorest quintiles earn on average 7% less than those graduates coming from the richest quintiles. This evidence shows that those coming from families with lower incomes will take longer periods to pay their student debt.

Research into salary differences among professionals from different socio-economic backgrounds in Chile shows that those who attended a fee-paying private school earn over 14% more than those from a subsidized school, and that the salary difference of these with those from public schools is 1.6% (Elfernan et al 2009); and again the evidence show that socio-economic background is an important factor in determining income in the labour market (Núñez and Gutiérrez, 2004).

In a complementary way, the study undertaken by the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals of the United Kingdom in 1999 found that the majority of prospective students from lower income sectors opted for shorter programmes of study in response to the cost of Higher Education, which means, according to Callender, that those students most adverse to indebtedness often opt for financial security, thus sacrificing the development of greater human and cultural capital. This is why they register in less prestigious or less advanced centers, with shorter programmes of study, geared towards lower status jobs and close to their homes. And finally earning less than those who attend college!

Conversely to the findings for developed countries like Great Britain and USA, in Chile the study of Olavarria and Allende (2013) shows that students coming from lower-income sectors have a favorable disposition to take on debt (in form of loans) to pursue Higher Education studies, recognizing that this is practically the only way to study or to access Higher Education. Contradictory situation because the evidence show that students from lower income homes obtain jobs with lower salaries, even when compared with students with the same degrees from other socio-economic sectors.

With this evidence in mind loans could be associated with improving access to Higher Education of students from lower income groups, mainly because their greater willingness to pay hoping for greater future labour income. But this comes with a little trap, they generate an indebtedness which is difficult to deal with, since the labour market confines them to lesser-paid jobs (than their colleagues from middle-income and better backgrounds) or which generates a burden that affects their family well-being at the time when people usually start a home and make long-lasting life investments.

In the last years the student movements in Chile have managed to change a little bit the situation about the indebtedness of the future students achieving tuition-free university education for the 50% Chile’s poorest students. But the implementation of that policy and the possibility (or maybe impossibility) of implementing a free for all education (as the movements wanted) put in serious burden the actual administration. (for an analysis and critics to this policy look at https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2016.86.9372 )

What do you think about student debt ?

Share your experiences!

Resteem and Follow me at @ciag

References

Callender, C., and Mason, G. (2017). Does student loan debt deter higher education participation? New evidence from England. Annals of American Political and Social Science.

Callender, C. and Jackson, J (2008) 'Does Fear of Debt Constrain Choice of University and subject of study?' Studies in Higher Education Vol 33 No 4, 405-429

Callender, C. and Jackson, J (2005)'Does Fear of Debt Deter Students from Higher Education?' Journal of Social Policy Vol 34/4 pp 509-540

Callender, C. (2003): «Attitudes to Debt: School Leavers’ and Further Education Students’ Attitudes to Debt and their Impact on Participation in Higher Education», Londres: Universities UK.

Callender, C. (2002): «The Cost of Widening Par- ticipation: Contradictions in New Labour’s Stu- dent Policies», Social Policy and Society 1: 83-94.

Carneiro, P. & Heckman J. (2002): «The Evidence on Credit Constraints in Post-secondary Schooling», The Economic Journal, 12: 705-734.

Mumper, Michael and Pamela Vander Ark (1991): «Evaluating the Stafford Student Loan Program: current Problems and Prospects for Reform», Journal of Higher Education, 62 (1): 62-78.

Elias, Peter, Abigail McKnight, Claire Simm, Kate Pur- cell and Jane Pitcher (1999): «Moving on: Graduate Careers three Years after Graduation», Manchester: CSU, DfEE.

Elfernan, R., Soto, C., Coble, D. & Ramos, J. (2009): «Determinantes de los salarios por carrera», working paper wp300, University of Chile, Department of Economics.

Núñez, J. and Gutiérrez, R. (2004): «Classism, Discrimination and Meritocracy in the Labor Market: the Case of Chile», working paper wp208, University of Chile, Department of Economics.

The previous research was adapted from a paper called “Student Debt and Access to Higher Education in Chile” (doi:10.5477/cis/reis.141.91) writen with Mauricio Olavarria (https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mauricio_Olavarria-Gambi)

Resteem and Follow me at @ciag

Spanish version of this post

@ciag/endeudamiento-estudiantil-y-acceso-a-la-educacion-superior